- 452 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Narcissus and Daffodil is the first book to provide a complete overview of the genus Narcissus. Prized for centuries in western Europe as an ornamental plant, it has recently attracted attention as a source of potentially valuable pharmaceuticals. In eastern European countries, however, Narcissus and other Amaryllidaceae have been valued as a sourc

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Narcissus and Daffodil by Gordon R Hanks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Alternative & Complementary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The biology of Narcissus

Gordon R. Hanks

INTRODUCTION

The genus Narcissus L. belongs to the Monocotyledon family Amaryllidaceae, to which it contributes some 80 species to its total of about 850 species in 60 genera (Meerow and Snijman, 1998). The taxonomy of Narcissus is difficult because of the ease with which hybridisation occurs naturally, accompanied by extensive cultivation, breeding, selection, escape and naturalisation (Webb, 1980; see Chapter 3 , this volume). The genus is distinguished from other Amaryllids by the presence of a perigonal corona structure (‘paraperigone’) forming a ring (‘cup’) or tube (‘trumpet’) (Dahlgren et al., 1985). Unlike other genera of the family, Narcissus has a mainly Mediterranean distribution, with a centre of diversity in the Iberian Peninsula, and the genus also occurs in south-western France, northern Africa and eastwards to Greece, while Narcissus tazetta is found not only in Spain and North Africa but in a narrow band to China and Japan (Grey-Wilson and Mathew, 1981). The eastwards distribution of N. tazetta may represent transfer along an ancient trade route, illustrating the long human interest in the genus as an ornamental plant, leading to its importance in commercial horticulture today (see Chapter 4 , this volume).

The survival of a number of Narcissus species has been threatened by past over-collection and habitat destruction, not only in Spain and Portugal but also in Morocco, Turkey and Belgium (Oldfield, 1989; Koopowitz and Kaye, 1990). The ‘Red List’ currently gives three Narcissus as ‘endangered’, five as ‘vulnerable’ and six as ‘rare’ (WCMC, 1999). In the light of the environmentalist concerns in the 1990’s, the collection of wild bulbs has been addressed by the industry. However, there is a need to maintain vigilance in the conservation of wild species and of their many variants, to establish genetic collections for future breeding programmes, and to develop sustainable production systems for their utilisation in commercial horticulture.

Hybridisation has resulted in commercial narcissus cultivars that are in most cases larger and more robust than their wild parents. Trumpet cultivars with coloured perianth and corona originated from N. pseudonarcissus and its varieties, and trumpet cultivars with white perianth and coloured corona from N. pseudo-narcissus ssp. bicolor. Large-cupped cultivars were the result of crosses between N. pseudonarcissus and N. poeticus, back-crossed with N. poeticus to yield the small-cupped cultivars. Multiheaded cultivars (the ‘Poetaz’ group) comprise mainly hybrids of N. poeticus and N. tazetta (Doorenbos, 1954).

Information about the commercial horticulture of narcissus can be found in Rees (1972, 1985b, 1992) and Hanks (1993). Texts on the genus include Bowles (1934), Jefferson-Brown (1969, 1991), Blanchard (1990) and Wells (1989).

THE GROWTH CYCLE UNDER NATURAL CONDITIONS

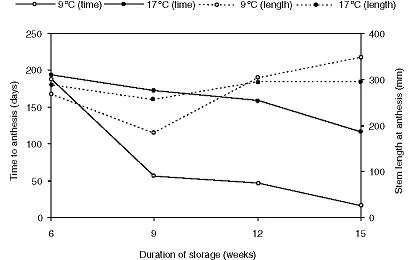

The native habitats of Narcissus species are very varied, and include grassland, scrub, woods, river banks and rocky crevices, in both lowland and mountain sites (Webb, 1980), and the ecology of natural populations of wild daffodil (N. pseudonarcissus) has been intensively studied (Caldwell and Wallace, 1955; Barkham, 1980a,b, 1992; Barkham and Hance, 1982). The bulk of Narcissus species are synanthous and spring-flowering. Shortly after flowering rapid leaf senescence occurs, followed by a summer underground (or ‘dormant’) period that allows the bulb to conserve moisture and avoid predators (the alkaloids which are largely the subject of the present volume may give further disincentive to predation). Although the term ‘dormancy’ is used, this refers mainly to the lack of any obvious external growth, for there is little physiological dormancy because, once the leaves and roots have died down, there is intense activity of primordia within the bulb (Kamerbeek et al. , 1970; Rees, 1971, 1972). There is a requirement for a cold period before normal growth resumes in the spring, an arrangement that avoids most damage due to frosts in winter. The cold requirement, however, is not particularly long nor cold, so that in climates like the UK or the Netherlands it is easily satisfied by normal winters. The flowering date is then dependent on spring temperatures being sufficiently high for growth, the resultant variations in flowering date being described by Rees and Hanks (1996). The cold requirement is not an obligate one for stem extension, as stem growth will proceed even without a cold treatment, albeit slowly and with a gradual loss of flowers due to bud abortion or other causes (Rees and Hanks, 1984). The effect of the cold period is to produce rapid, synchronous stem extension and progress to anthesis (Figure 1.1). In nature, this occurs at a time when competition for pollinator insects is low and growth is relatively unhindered by shading or other competition from grasses or deciduous trees (Caldwell and Wallace, 1955; Shmida and Dafni, 1990).

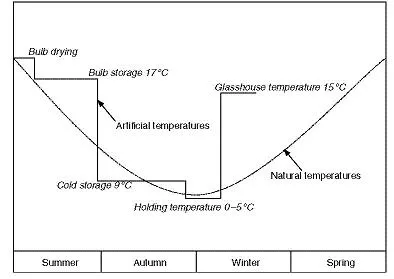

The growth cycle just described has been utilised in commercial horticulture, being manipulated by controlled-temperature storage (Figure 1.2) to obtain ‘forced’ flowers in glasshouses over an extended season (ADAS, 1985; De Hertogh, 1989; Anon., 1998). Geophytic plants such as bulbs and corms lend themselves to horticultural usage, since their storage organs can be conveniently treated (whether by pesticides or environmental treatments), transported and traded, yet can be brought into flower in a relatively short time. The rapid growth and flowering of spring bulbs is dependent on the conversion of insoluble reserves, such as starch, into readily translocatable soluble sugars. In order to understand these processes and develop improved methods of flower forcing, carbohydrate metabolism and the related hormone-mediated processes have been investigated in flower-bulb crops, although less so in the case of narcissus than in species such as tulip and iris, perhaps because of the presence in narcissus of mucilaginous sap, which interferes with chemical extraction and separation. Carbohydrate metabolism in narcissus has been studied by Grainger (1941), Thomas et al. (1995) and Ruamrungsri et al. (1999), and the polysaccharides by Balbaa et al. (1980) and Rakhimov and Zhauyn-baeva (1997). The auxins of narcissus have been studied by Edelbluth and Kaldewey (1976), gibberellins by Aung et al. (1969), cytokinins by van Staden (1978) and Belynskaya et al. (1990) and ethylene by Staby and De Hertogh (1970).

Figure 1.1 The effect of bulb storage at 9 or 17 °C for 6–15 weeks on (left axis) the time to anthesis (days in a glasshouse at 16 °C) and (right axis) stem length at anthesis for narcissus ‘Fortune’ (data from Rees and Hanks, 1984).

Figure 1.2 The temperature sequence during bulb forcing, compared with natural temperatures (after A.R. Rees, personal communication).

Cultivars derived from the N. tazetta group are unusual in that, while still ‘summer dormant’, they have no cold requirement and growth and anthesis can occur before winter if all other conditions are favourable (although cold treatments can increase stem length and speed anthesis; Roh and Lee, 1981; Rees and Hanks, unpublished data in Hanks, 1993). Tazetta narcissus, unlike most narcissus, respond to ethylene, which promotes flowering (Imanishi, 1997). These characteristics have enabled horticulturists to exploit Tazettas for flower production over a long season.

A few species – N. elegans, N. serotinus, N. viridiflorus and N. humilis – are autumn-flowering and generally hysteranthous. Studies on N. tazetta and other geophytes suggest that the syanthous-hysteranthous habit is facultative, with hysteranthy tending to be expressed in xeric habitats (Evenari and Gutterman, 1985; Halevy, 1990). The autumn-flowering species have not yet been exploited horticulturally, probably because their flowers are small or insignificant, although they clearly have potential for producing new types of commercial cultivars (Koopowitz and Kaye, 1990).

MORPHOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT

The flowering plant

Detailed reports of the morphology and development of the narcissus plant have been given by Huisman and Hartsema (1933), Chan (1952), Okada and Miwa (1958) and Rees (1969, 1972), from which the following description has largely been compiled.

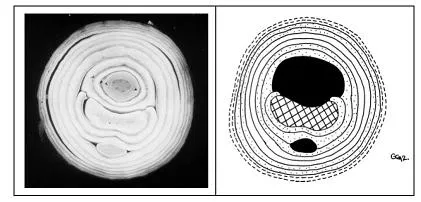

Bulb structure and bulb unit development

The ‘dormant’ narcissus bulb in autumn consists of a more-or-less disc-shaped stem plate (base or basal plate) bearing adventitious roots below and storage organs (bulb scales) surrounding a bud above. The bulb ‘scales’ consist of true scales, which are almost entirely within the bulb and serve a purely storage function, and the bases of foliage leaves; after anthesis the base of the flower stalk becomes flattened and is also scale-like in function. Leaf bases can be distinguished from bulb scales because the former have a thicker tip and a scar where the leaf lamina became detached. In the ‘model’ case of a narcissus bulb with a single, terminal growing point (a ‘single nosed round’ bulb), a transverse section of the bulb in autumn shows a series of concentric ‘scales’ surrounding the old flower stalk base and a terminal bud (Figure 1.3). The exception to the concentric nature of the ‘scales’ is that the inner leaf, which subtends the flower, has a semi-circular base with keeled margins only partly enclosing the flower stalk. The terminal bud consists of bulb scales surrounding leaves and a flower. In addition to the terminal bud, there is also a lateral bud.

Figure 1.3 Left: transverse section of single-nosed, flowering-size narcissus ‘Carlton’ bulb in autumn. Right: diagram showing the generations of bulb units with their component parts. Shaded areas: the terminal (above) and lateral (below) units with next spring’s leaves and flower (individual bulb scales, leaves and flower not shown). The unit that bore last spring’s leaves and flower comprises the flattened remains of the stem (cross-hatched), three leaf bases (the innermost semi-sheathing) (stippled) and two bulb scales (unshaded). Beyond these scales are the remains of bulb scales and leaf bases of previous generations of bulb units, which are eventually shed as dry tunic (broken lines). (After Hanks (1993); reprinted from The Physiology of Flower Bulbs, ©1993, page 466, with the permission of Elsevier Science.)

The narcissus is a perennial branching system, and Rees (1969, 1972, 1987) used the term ‘bulb unit’ to describe each annual increment of growth, thereby distinguishing these structures from shorter lived entities such as the bulbs of tulip, where new bulbs (daughter bulbs) become separate entities each year. In narcissus, the growing point produces a new bud with bulb scales and le...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PREFACE TO THE SERIES

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- FIGURES

- PLATES

- 1. THE BIOLOGY OF NARCISSUS

- 2. THE FOLKLORE OF NARCISSUS

- 3. CLASSIFICATION OF THE GENUS NARCISSUS

- 4. COMMERCIAL PRODUCTION OF NARCISSUS BULBS

- 5. ECONOMICS OF NARCISSUS BULB PRODUCTION

- 6. ALKALOIDS OF NARCISSUS

- 7. PRODUCTION OF GALANTHAMINE BY NARCISSUS TISSUES IN VITRO

- 8. NARCISSUS AND OTHER AMARYLLIDACEAE AS SOURCES OF GALANTHAMINE

- 9. STUDIES ON GALANTHAMINE EXTRACTION FROM NARCISSUS AND OTHER AMARYLLIDACEAE

- 10. GALANTHAMINE PRODUCTION FROM NARCISSUS: AGRONOMIC AND RELATED CONSIDERATIONS

- 11. EXTRACTION AND QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF AMARYLLIDACEAE ALKALOIDS

- 12. SYNTHESIS OF GALANTHAMINE AND RELATED COMPOUNDS

- 13. COMPOUNDS FROM THE GENUS NARCISSUS: PHARMACOLOGY, PHARMACOKINETICS AND TOXICOLOGY

- 14. GALANTHAMINE: CLINICAL TRIALS IN ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

- 15. SCREENING OF AMARYLLIDACEAE FOR BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES: ACETYLCHOLINESTERASE INHIBITORS IN NARCISSUS

- 16. NARCISSUS LECTINS

- 17. NARCISSUS IN PERFUMERY

- 18. HARMFUL EFFECTS DUE TO NARCISSUS AND ITS CONSTITUENTS

- 19. REVIEW OF PHARMACEUTICAL PATENTS FROM THE GENUS NARCISSUS