- 520 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded

About this book

A clear and concise survey of the major themes and theories embedded in the history of life science, this book covers the development and significance of scientific methodologies, the relationship between science and society, and the diverse ideologies and current paradigms affecting the evolution and progression of biological studies. The author d

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded by Lois N. Magner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Medicine1

THE ORIGINS OF THE LIFE SCIENCES

Modern biology encompasses both the oldest and newest scientific disciplines, but the term biology was first introduced at the beginning of the nineteenth century to signify a departure from the ancient conventions of natural philosophy. Most simply defined as the science of living things, biology includes anatomy and physiology, embryology, cytology, genetics, molecular biology, evolution, and ecology. Like all the sciences, biology has roots reaching back into prehistory. Indeed, the most important lessons of all to human survival are aspects of biology—agriculture, animal husbandry, and the art of healing. Innovations in these areas among prehistoric peoples would involve the most ephemeral products of human endeavor. Stone tools, weapons, pottery, glass, and metals leave a more permanent record than a new understanding of the cycles of nature, or the relationship between the breath and the beat of the heart to life itself. Yet it is ultimately on such biological wisdom that human survival and cultural evolution depended.

Driven by necessity, the earliest human beings must have been keen observers of nature. Anthropologists and ethnobotanists have discovered that so-called primitive peoples establish fairly sophisticated classification schemes as a means of understanding and adapting to their environment. Objects may be divided into categories such as the raw and the cooked, the wet and the dry, but the subdivisions within such schemes may reflect keen insights into the medicinal properties of plants and animal products. Even such a seemingly simple division as edible and inedible requires considerable experimentation. Primitive people also learned from experience that a series of operations could transform things from one class to another, For example, in the preparation of manioc both a food and a poison are produced.

Biology as the study of living things probably began with the emergence of Homo sapiens sapiens some 50,000 years ago. Ancient human beings living as hunter-gatherers during the Paleolithic Era, or Old Stone Age, manufactured crude tools made of chipped stones. Presumably these ancient people also produced useful inventions that were fully biodegradable and left no trace in the fossil record, such as digging sticks, ropes, bags, and baskets for carrying and storing food. But the inventions of the utmost importance in the separation of human beings from the ways of their ape-like ancestors were fire, speech, abstract thought, religion, and magic. At this stage, conscious of themselves as special entities, human beings could begin to confront the fundamental problems of existence—birth and death, health and disease, pain and hunger—in new ways.

Since the transition from “prepeople” to fully modern human status, cultural evolution, a phenomenon unique to humankind, has taken precedence over biological evolution, a process shared with the rest of the organic world. Another great transition took place about 10,000 years ago when agriculture was invented. The transition from the hunter-gatherer mode of food production to farming and animal husbandry is known as the Neolithic Revolution. In the process of domesticating piants and animals, human beings, too, became domesticated and enmeshed in ways of living, thinking, and planning that revolved around the natural forces and cycles controlling their new enterprises. Scientists and historians were once most interested in the when and where of the emergence of agriculture, but given the fact that hunter-gatherers may enjoy a better diet and more leisure than agriculturists, the greater puzzle is actually the how and why. In other words, when progress became a concept to be analyzed rather than an inevitable step in human history, the Neolithic transformation could no longer be seen as an early and inevitable step along the road to modernity.

Anatomy, both human and animal, was one of the earliest components of biological knowledge. Among ancient peoples, fear and respect for the dead led to elaborate funerary rites involving the manipulation and perhaps mutilation of corpses. Bodies might be cremated, buried, or preserved after removal of certain organs. Burial customs may reflect compassion and respect, as well as attempts to placate the spirits of the dead and make it impossible for them to return, as they sometimes seemed to do in dreams. Once death could be anticipated and rationalized, attempts could be made to ward it off by both magical and rational means. Primitive attempts at wound management and surgery would provide knowledge of human anatomy and the location of vulnerable sites on and in the body. Observations made while caring for the sick and the dying would have provided important physiological information, such as the importance of the breath, heartbeat, pulse, blood, and body heat.

Knowledge of animal anatomy and behavior is important to the hunter, herdsman, butcher, cook, healer, and shaman, Animals have served as totems of tribes or clans, and animal organs and behavior have been used as omens. Because divination and prophecy depended on the appearance and behavior of various animals, any peculiarity of shape, color, or behavior could decide the fortunes of the tribe and the fortune-teller, Following the natural migrations of animals forces hunters and herders to study their natural behavior, but the domestication of animals would encourage more detailed observations and attempts to select and breed the best of the herd.

Human cultural evolution was profoundly influenced by the domestication animals, especially the horse. Dogs, pigs, cattle, sheep, and goats were probably domesticated long before humans successfully captured, domesticated, and bred horses. The earliest evidence of the domestication of horses appears about 6,000 years ago in central Asia. Horses were widely dispersed throughout the Eurasian steppes some 35,000 years ago. They began to decline about 10,000 years ago. Archaeological sites in Ukraine and Kazakhstan from about 6,000 years ago contain the remains of horses, including some with tooth wear that was probably caused by the use of bits. Although other animals were primarily valuable as sources of food, horses provided the power to transform work, transportation, trade, and warfare. The increased danger posed by men with horses might have stimulated the construction of cities as a way of providing protection from horse-based armies.

In search of the ancestors of domesticated horses, scientists have looked for a common ancestor, an equine Eve, among the diverse family lines of modern horses. Some scientists believe that the large diversity found in modern horses means that they did not derive from a single population. Studies of DNA from modern horses and DNA recovered from the bones of horses preserved in the Alaskan permafrost suggest highly diverse and ancient lines of descent. Interactions between humans and horses might, therefore, have taken place well before the first archaeological evidence of domestication.

BIOLOGY AND ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS

The invention of science is generally credited to the Greek natural philosophers who lived during the sixth century B.C. This assumption may be largely a product of Eurocentric bias and ignorance about other ancient civilizations. It is not clear how much Greek civilization was influenced by the great civilizations that developed along the valleys of the Nile, Tigris-Euphrates, Yellow, and Indus rivers as much as 5000 years ago. Although these cultures left their mark in terms of archeological monuments, artifacts, and texts, only a small portion of what they achieved was recorded and preserved. Because of the paucity of sources, we undoubtedly have a greatly distorted view of their real accomplishments.

The emphasis on the traditional Western heritage from Greek culture has resulted in the neglect of earlier civilizations and other traditions. Traditionally, India and China were virtually excluded from the general history of science and medicine, except for accounts of exotic medical practices and the invention of printing and gunpowder. Over the course of thousands of years, these complex civilizations developed unique approaches to fundamental questions about the nature of hutnan beings and their relationship to nature. Scholarly explorations of science and philosophy in the context of Chinese and Indian history are relatively new.

Pioneering studies of science and civilization in China led some scholars to suggest that no system of knowledge equivalent to Western “biology” appeared in classical Chinese science or medicine, but biology did not exist as a distinct field in Western science until the nineteenth century. Certainly observations and theories concerning human health and disease, plants and animals, the natural world in general can be found in ancient Chinese writings. They were, however, dispersed throughout a scholarly tradition very different from that of the West. Ideas about vital phenomena and chemical processes can be found in the writings of ancient Chinese alchemists, physicians, and philosophers. Chinese alchemy, especially the ideas of the Taoists, could be considered part of the science of life. Alchemists are often thought of as mystics engaged in the impossible quest for the philosopher’s stone that would allow them to transform lead into gold. Taoist alchemists, however, were more concerned with the search for the great elixirs of life, drugs that would provide health, longevity, and even immortality. While the writings of the alchemists were often obscure, the knowledge accumulated by illiterate craftsmen, herbalists, folk healers, and fortune-tellers generally remained outside the scholarly tradition and has been lost to history.

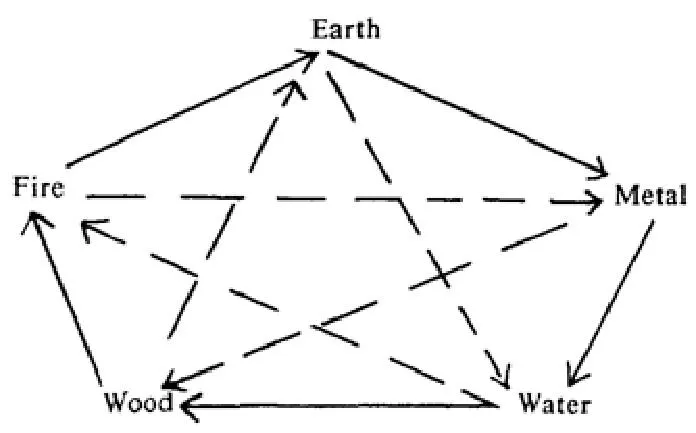

Within Chinese classical science and philosophy, the body of ideas and observations belonging to medicine would come closest to providing knowledge corresponding to the life sciences. Classical scholars explained the unity of nature, life, health, disease, and medicine in terms of the theory of yin and yang and the five phases. The five phases are sometimes called the “five elements,” but this is generally considered a mistranslation based on a false analogy with the four elements of ancient Greek science. The Chinese term actually implies transition, movement, or passage rather than the stable, homogeneous chemical entity implied by the term element. Accepting the impossibility of translating the terms yin and yang, scholars simply retain the terms as representations of all the pairs of opposites that express the dualism of the cosmos. Thus, yang corresponds to that which is masculine, light, warm, firm, heaven, full, and so forth, while yin is characterized as female, dark, cold, soft, earth, empty. Rather than simple pairs of opposites, yin and yang represent relational concepts; that is, members of a pair would not be hot or cold per se, but only in comparison to other entities or states. Applying these concepts to the human body, the inside is relatively yin, whereas the outside in relatively yang, and specific internal organs are associated with yang or yin.

The five phases. As individual names or labels for the finer ramifications of yin and yang, the five phases represent aspects in the cycle of changes. The five phases are linked by relationships of generation and destruction. Patterns of destruction may be summarized as follows: water puts out fire; fire melts metal; a metal ax will cut wood; a wooden plow will turn the earth; an earthen dam will stop the flow of water. The cycle of generation proceeds as water produces the wood of trees; wood produces fire; fire creates ash, or earth; earth is the source of metal; when metals are heated they flow like water.

According to scholarly tradition, the principle of yin-yang is the basis of everything in creation, the cause of all transformations, and the origin of life and death. The five phases—water, fire, metal, wood, and earth—may be thought of as finer textured aspects of yin and yang. The five phases represent aspects in the cycle of changes. Classical Chinese medical practice was based on the theory of systematic correspondences, which linked the philosophy of yin and yang and the five phases with a complex system that purportedly explained the functions of the constituents of the human body. Thus, the goal of classical Chinese anatomy was to explain the body’s functional systems and the Western distinction between anatomy and physiology was essentially irrelevant. Within this philosophical system, Chinese scholars were able to accept the relationship between the heart and pulse and the ceaseless circulation of the river of blood within the human body. It was not until the seventeenth century that these concepts were incorporated into Western science through the experimental physiology of William Harvey (1578–1657).

Many aspects of the history of the Indian subcontinent are obscure before the fourth century B.C., but archaeologists have discovered evidence of the complex Indus River civilization that flourished from about 2700 to 1500 B.C. The sages of ancient India had little interest in chronology or the separation of mythology and history, but traces of their ideas about the nature of the universe and the human condition can be found in the Vedas, sacred books of divinely inspired knowledge. Brahma, the First Teacher of the Universe, one of the major gods of Hindu religion, was said to be the author of a great epic entitled Ayurveda, The Science of Life. After oral transmission through a long line of divine sages, fragments of the sacred Ayurveda were incorporated into the written texts that now provide glimpses into ancient Indian concepts of life, disease, anatomy, physiology, psychology, embryology, alchemy, and medical lore. A striking difference between Indian religions and those of the West is the Hindu concept of a universe of immense size and antiquity undergoing a continuous process of development and decay. Indian scholars excelled in astronomy and mathematics, especially the ability to manipulate the large numbers associated with mythic traditions concerning the duration of the cosmic cycle.

Health, illness, and physiological functions were explained in terms of three primary humors, which are usually translated as wind, bile, and phlegm, in combination with blood. The concept of health as a harmonious balance of the primary humors is similar to fundamental Greek concepts, but the Ayurvedic system provided further complications. The body was composed of a combination of the five elements—earth, water, fire, wind, and empty space—and the seven basic tissues. Five separate winds, plus the vital soul, and the inmost soul also mediated vital functions. Ayurvedic writers also expressed considerable interest in the fundamental question of conception and development. According to the Ayurvedic classics, living creatures fall into four categories as determined by their method of birth: from the womb, from eggs, from heat and moisture, and from seeds. Within the womb, conception occurred through the union of material provided by the male and female parents and the spirit, or external self. The development of the fetus from a shapeless jelly-like mass to the formed infant was described in considerable detail in association with the signs and symptoms characteristic of the stages of pregnancy.

The Ayurvedic surgical tradition presents an interesting challenge to the Western assumption that progress in surgery follows the development of systematic human dissection and animal vivisection. Religious precepts prohibited the use of the knife on human cadavers, but Ayurvedic surgeons performed major operations such as couching the cataract, amputation, trepanation, lithotomy, cesarean section, tonsillectomy, and plastic surgery. The study of human anatomy, or the science of being, was justified as a form of knowledge that helped explicate the relationship between human beings and the gods. Despite barriers to systematic dissection of human cadavers, Indian scholars developed a remark-ably detailed map of the body including a complex system of vital points, or marmas. Injuries at such points could result in hemorrhage, permanent weakness, paralysis, chronic pain, deformity, loss of speech, or death. Obviously, knowledge of such points was critical to ancient physicians and surgeons, who had to take the system into account when performing operations, treating wounds, or prescribing bloodletting and cauterization. Knowledge of the system is also of interest to certain contemporary healers, such as those who use the points as a guide to therapeutic massage. Indeed, Ayurvedic medicine is a living tradition that brings comfort to millions of people, while the ancient classics provide valuable medical insights and inspiration for modern physicians and scientists.

MESOPOTAMIA AND EGYPT

Along the great river valleys of Mesopotamia and Egypt, human life and welfare depended on the cyclic flooding and retreat of the great rivers. Complex agricultural and engineering activities had to be planned, directed, and supervised by knowledgeable authorities. The priests and nobles who directed this system dominated the way their subject populations thought about nature. The ancient myths of the separation of chaos into dry land and water and the development of living things from the mud are in essence the life story of these first civilizations. These myths served powerful central governments in dealing with the mundane problems of agriculture—land surveying, irrigation and flood control, storing food for bad years—and in explaining the capriciousness of nature. For the privileged members of the priesthood, knowledge of biological and astronomical phenomena was a valuable professional monopoly, not the subject matter for secular scientific inquiry.

Unpredictable and dangerous waters played a prominent role in Mesopotamian cosmology, as might be expected in an area subject to unpredictable flooding. Early Mesopotamian myths described the earth and heavens as flat disks supported by water. Somewhat later the heavens were described as a hemispherical vault which rested on the waters that surrounded the earth. The heavenly bodies were gods who dwelt beyond the waters above the heavens and came out of their dwelling places for their daily journey through the heavens, Since the gods controlled events on earth, the motions of the heavenly bodies were closely studied to reveal the intentions and designs of the gods.

According to Egyptian cosmology, the world was rather like a rectangular box. The earth was at the bottom, making that part of the box somewhat concave. Four mountain peaks at the corners of the earth supported the sky, while the Nile was a branch of a universal river that flowed around the earth. This river carried the boat of the sun god on his journey across the sky. Seasonal changes and the annual Nile flood were explained by deviations in the path taken by the boat.

Creation myths explained how the world came into existence from a primeval chaos of waters. Matings between male and female gods in the time of chaos brought forth the heavens, earth, air, and the natural forces that were personified by various gods. The gods organized the universe out of the original chaos, separating the land from the waters much as the first settlers had reclaimed the earth from the waters. Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, in their political organization, scientific interests, and religions, reflect the differences in the patterns of the great rivers. The Nile floods were predictable, beneficent, and eagerly anticipated. Egyptian dynasties were generally long-lived, rigid, and complacent. Great efforts were expended in creating appropriate tombs for the mummified remains of the Pharaohs. The floods of the Tigris and Euphrates, in contrast, were unpredictable and frightening events. Governments in Mesopotamia were more transient and the future always uncertain. Astrology and divination were the tools and weapons with which Mesopotamian priests wrestled with the gods and the chaotic forces of nature.

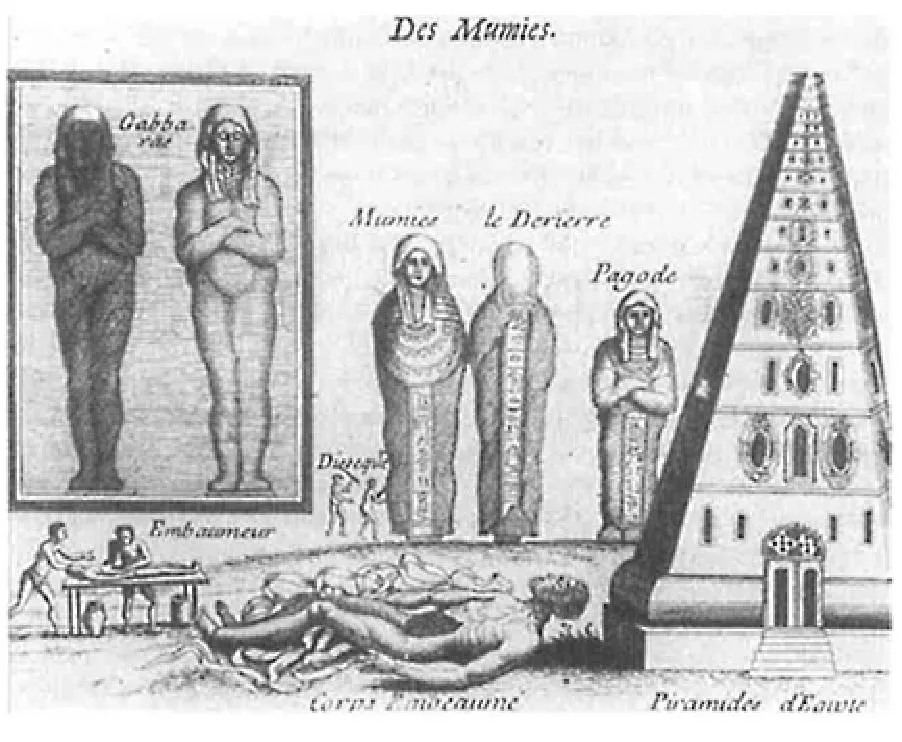

Egyptian mummies, pyramids, and the embalming process as depicted in a seventeenth-century French engraving

Despite great accomplishments during the high Bronze Age, these civilizations remained essentially static while various technological innovations transformed cultures that had been at the fringes of Bronze Age civilization. The smelting of iron and the use of a simple alphabetic script created a new cultural revolution. Sometime in the second millennium B.C., a tribe in the Armenian mountains developed an efficient method of smelting iron. Originally quite secret, the method became generally known after about 1000 B.C. Iron was used in weapons and for agricultural implements, which led to more efficient exploitation of the lands to the north. With iron weapons, barbarians like the Greek tribes were able to conquer rich Bronze Age cultures.

Long after the civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India had reached their peak and entered into periods of decline or chaos, Greek civilization seems to have emerged with remarkable suddenness, like Athena from the head of Zeus. This impression is certainly false, but it is difficult to correct because of the paucity of materials from the earliest stages of Greek history. What might be called the prehistory of Greek civilization can be divided into the Mycenaean period, from about 1500 to the collapse of Mycenaean civilization about 1100 B.C., and the so-called Dark Ages from about 1100 to 800 B.C. Fragments of the history of this era have survived in the great epic poems known as the Iliad and the Odyssey, traditionally attributed to the ninth-century poet known as Homer. Ancient concepts of life and death, the relatio...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- 1 The Origins of the Life Sciences

- 2 The Greek Legacy

- 3 The Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution

- 4 The Foundations of Modern Science: Institutions and Instruments

- 5 Problems in Generation: Preformation and Epigenesis

- 6 Physiology

- 7 Microbiology, Virology, and Immunology

- 8 Evolution

- 9 Genetics

- 10 Molecular Biology