eBook - ePub

Temperament and Personality Development Across the Life Span

- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Temperament and Personality Development Across the Life Span

About this book

This is the third book in a series of Across the Life Span volumes that has come from the Biennial Life Span Development Conferences. The authors--well known in their fields--present theoretical and research issues important for the understanding of temperament in infancy and childhood, as well as personality in adolescence and adulthood. Current findings placed within theoretical and historical contexts make each chapter distinctive. The chapter authors focus on their work and its implications for temperament and personality issues across the life span. In addition, they include summaries of research by other investigators and theorists, placing their work and that of others in a lifespan perspective.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Temperament and Personality Development Across the Life Span by Victoria J. Molfese,Dennis L. Molfese,Robert R. McCrae in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Temperamental Substrates of Personality Development

H. Hill Goldsmith

Kathryn S. Lemery

Nazan Aksan

Kristin A. Buss

University of Wisconsin - Madison

Kathryn S. Lemery

Nazan Aksan

Kristin A. Buss

University of Wisconsin - Madison

The chapter title implies that a set of attributes called temperament is basic to later personality and uses the chemical term substrates to refer to the relationship. Our use of the term substrates has a sense analogous to its use in chemistry. Substrates are substances that are acted on and modified by other influences — in chemistry, by enzymes and in human development, by the biological and social environment. That is, from an individual difference perspective, temperamental traits represent raw material that is modified —and sometimes radically changed —to yield the recognizable features of mature human personality. Like chemical substrates, which are generally synthesized from other compounds, behavioral temperamental substrates do not come ready-made with the neonate. They too are constructed from other substrates. In some cases, the substrates of temperament might be even more basic perceptual and motor characteristics; however, we typically think of temperament as a basic behavioral level of organization that has biological substrates.

As we see it, there are three readily researchable issues that make the case for temperamental substrates of later personality. First is the question of origins of temperament. We focus mainly on biological variables, with full cognizance that some biological processes can be correlated with temperament without acting causally on its development. Second is the question of continuity of temperament. Unless temperament itself is stable under common conditions, it appears ill-suited for the role of personality substrate. We consider different meanings and different degrees of continuity. The third question is perhaps the most important one: What evidence can we adduce that temperament is crucial for development — does it hold functional significance for other aspects of personality and adaptation?

In this chapter, we do not dwell on definitional issues, which are treated by Goldsmith et al. (1987), Kagan (1998), and Rothbart and Bates (1998), among others. We simply define temperament as early developing individual differences in tendencies to experience and express emotions, including their regulatory aspects. To make our task in this chapter manageable, we consider the three questions posed earlier. We focus only on four substantive areas of temperament: fearfulness, anger proneness, positive affectivity, and emotion regulation and pay particular attention to fearfulness and emotion regulation.

These four substantive domains require some specification. Fearfulness is the broadest category; it is a "family" that includes some members that we might eventually learn are unrelated. (See Kagan 1994, chapter 3 for more detail.) Some results that we review or report use Kagan's (1994) concept of behavioral inhibition, which refers to initial fear and avoidance in response to unfamiliar events. Other studies concern shyness, which is social fear or anxiety exhibited when unfamiliar persons are present (see Rubin & Stewart, 1996 for review). Behaviorally inhibited children are generally shy, but shyness is a narrower construct. One measure that we employ is the Children's Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart & Ahadi, 1994; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994), which has both Shyness and Fear scales, with items such as "Seems to be at ease with almost any person (reversed)" (Shyness) and "Is afraid of elevators" (Fear). Yet another member of the fear family is evaluation anxiety, which has a social context but is more concerned with how the self is viewed by others. Anger proneness is perhaps a less heterogeneous family, or perhaps it has simply not been investigated enough for us to appreciate its nuances.

Positive affectivity is the label for a complex family of emotional states or individual differences, some of which are independent. Researchers differentiate positive affectivity into contentment and exuberance on a basis of intensity of expression and types of evoking stimuli, a characterization very similar to Rothbart's distinction between low pleasure and high pleasure on the CBQ (Rothbart, 1989). High pleasure overlaps with the construct of sensation seeking (Zuckerman, 1984), whereas low pleasure refers to the enjoyment of low intensity stimulation, expressed in ways that do not involve high activity level. The positive affectivity domain can also be parsed into pregoal attainment and postgoal attainment positive affect (Davidson, 1994). The concept of pregoal attainment positive affect incorporates approach motivation and holds implications for a large literature in that area (Depue & Collins, in press; Wise, 1988). Emotional regulation is perhaps the broadest, most complex, and least fully conceptualized aspect of temperament. One definition is that "Emotion regulation consists of the extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one's goals" (Thompson, 1994, pp. 27-28). Regulation can be conceptualized in many ways; in this chapter, we are concerned primarily with attentional processes and the ability to intentionally inhibit ongoing behaviors.

Our review of the literature is selective and largely eschews historical perspective. We focus on a series of recent results from our own research group. We conducted several studies of temperament and emotional development using children ranging in age from early infancy into the school years. Some of our studies included twins and their families, whereas others involved singletons.

Biological Origins of Temperament

Behavior-Genetic Studies of Temperament

Because they are the only entity reliably transmitted with a secure biological mechanism between generations, genes are a fundamental underpinning of the biology of behavior. Therefore, a comprehensive study of temperament must take genetics into account. Temperament has been studied extensively although somewhat narrowly throughout infancy and childhood using behavior-genetic methodology. The narrowness of this research stems from the widespread use of parental report of temperament that has recognized strengths and weaknesses reviewed by us (Goldsmith & Rieser-Danner, 1990; Rothbart & Goldsmith, 1985) and many others. Another source of narrowness is the use of twins in the great majority of studies rather than relying on siblings or adoptees as subjects. Between 1979 and 1994 there have been only a few observational studies of temperament (e.g., Goldsmith & Campos, 1986; Lytton, 1980; Plomin & Foch, 1980; Plomin & Rowe, 1979; Wilson & Matheny, 1983), with a trend for behavioral inhibition (DiLalla, Kagan, & Reznick, 1994; Matheny, 1989) and activity level (Eaton, McKeen, & Lam, 1988; Saudino & Eaton, 1991) to be most intensely studied. Observational and laboratory-based studies are becoming more common and larger in scale (Emde & Hewitt, in press; Matheny, 1984).

In one of the more interesting analyses, DiLalla et al. (1994) examined the heritability of inhibition using both a dimensional and a categorical, extreme group approach. They used data collected from over 100 same-sex 24-month-old twin pairs from the MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study (Emde & Hewitt, in press). Under the dimensional approach, DiLalla et al. found that heritability for inhibited behavior for the entire sample was significant, yielding intraclass correlations of .82 for monozygotic twins and .47 for dizygotic twins. Using the categorical approach, they identified probands whose scores on inhibition were in the top 20% of the distribution. Using DF regression (DeFries & Fulker, 1985), the heritability estimate obtained by DiLalla et al. for the extreme group was higher—but not significantly so —than the estimate obtained from the total sample. In addition, when they used different thresholds to define more extreme groups, heritability estimates increased. This study (DiLalla et al., 1994) tentatively supports the hypothesis that extreme inhibition is influenced more by heredity than mid-range inhibition, but it certainly does not conclusively demonstrate this phenomenon.

Viewing this literature as a whole, variation in temperamental traits appears to be moderately genetically influenced, with only rather modest and scattered evidence for shared environmental effects. Negatively valenced temperamental traits (e.g., fear, anger proneness) are primarily genetically influenced, whereas more positively valenced temperamental traits (e.g., pleasure) show evidence for shared environmental effects as well (Goldsmith, Buss, & Lemery, 1997, Goldsmith, Lemery, Buss, & Campos, 1999). Behavioral inhibition also has moderate genetic underpinnings, with little evidence for the effects of the shared environment.

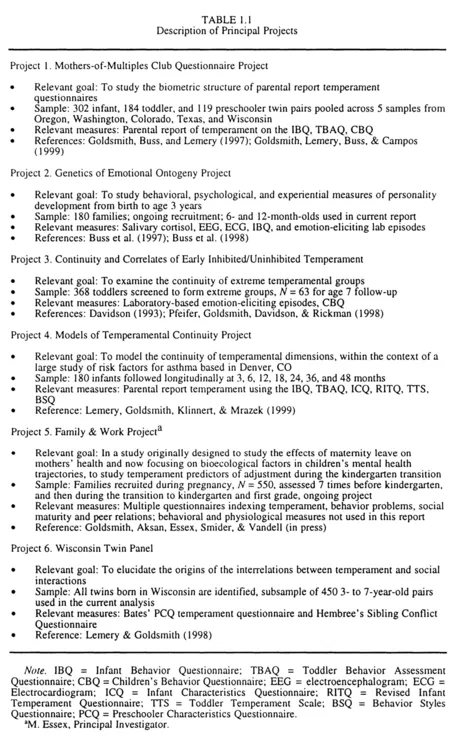

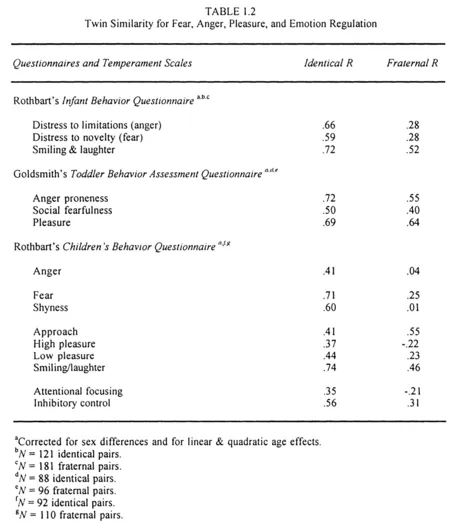

Turning to our own research, in Project 1 (see Table 1.1) we documented heritable influences on a variety of maternally reported temperamental dimensions from infancy to preschool-age ranges (Goldsmith et al., 1997; Goldsmith, Lemery, et al., 1999). In contrast to instruments on which prior literature was based, the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ; Rothbart, 1981), the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ; Goldsmith, 1996) and the CBQ offer assessment of positive affectivity (separately from negative affectivity) and of emotional regulation. Table 1.2 summarizes the findings from these studies. As expected, we found evidence for additive genetic effects for temperament scales and factors related to negative affect (e.g., fear, anger proneness) with little or no evidence for the shared environment.

Two other findings were relatively novel. First, we found evidence for moderate shared environmental variance for scales related to positive affect for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. This finding does have precedence. There is evidence for shared environmental effects on examiner ratings of person interest during cognitive testing (Goldsmith & Gottesman, 1981); on videotaped laboratory-based measures of smiling (Goldsmith, 1986; Goldsmith & Campos, 1986); on home-based observations of positive activity (Lytton, 1980); and on questionnaire measures of zestfulness (Cohen, Dibble, & Graw, 1977). What are the experiential processes underlying this

shared environmental variance? Of course, we do not know the number, much less the identity, of these processes. The leading candidate may be some feature of maternal behavior jointly experienced by the twins. We speculate that twin similarity for attachment security in respective twin-mother relationships might play a role because attachment security is related to positive affectivity (Mangelsdorf, Diener, McHale, & Pilolla, 1993). On the other hand, other features of maternal personality such as extraversion could be influential as sources of common experience for the twins. We must also acknowledge the possibility of a social desirability (on the part of the parent who completed the questionnaires) explanation because preliminary research indicates that the TBAQ Pleasure scale is more strongly related to a trial measure of content-balanced social desirability than other TBAQ scales (Goldsmith, 1996).

Our second novel finding concerned genetic contributions to emotion regulation. The Effortful Control factor of the CBQ represents another understudied area in the behavior-genetic literature. The two CBQ scales (Attention Focusing and Inhibitory Control) that load most highly on this factor play crucial roles in the regulation of emotion. For instance, the ability to allocate attention flexibly allows children to modulate or regulate their exposure to stressful situations (Rothbart, 1989; Rothbart, Posner, & Rosicky, 1994; Ruff & Rothbart, 1996). The domain of emotion regulation is currently one of the most intensively studied areas in the developmental literature (see Fox, 1994, for review). Despite the surge of recent interest in the topic, the origins of emotion regulation remain largely unexplored (Mangelsdorf, Shapiro, & Marzolf, 1995). Our findings offer the initial evidence of heritable variation ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Temperamental Substrates of Personality Development

- 2. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Temperament in Preschoolers

- 3. Linking Nutrition and Temperament

- 4. Stability of Temperament in Childhood: Laboratory Infant Assessment to Parent Report at Seven Years

- 5. The Meaning of Parental Reports: A Contextual Approach to the Study of Temperament and Behavior Problems in Childhood

- 6. Temperament and Parent-Child Relations as Interacting Factors in Children's Behavioral Adjustment

- 7. Madness Beyond the Threshold? Associations Between Personality and Psychopathology

- 8. Personality and Subjective Well-Being Across the Life Span

- 9. Personality Development From Adolescence Through Adulthood: Further Cross-Cultural Comparisons of Age Differences

- 10. A New Approach to Modeling Bivariate Dynamic Relationships Applied to Evaluation of Comorbidity Among DSM-III Personality Disorder Symptoms

- Author Index

- Subject Index