1

Scenes from the Nonlinear House of Panic

Our understanding of social groups and organizations has progressed by gradual increments over the last century and then, suddenly, there was a very different theory—one that emphasizes the footprints of change and the many shapes and sizes that there could be. Nonlinear dynamical systems theory (NDS), which is also known colloquially as chaos theory or complexity theory, is the study of the events that change over time and space. By nonlinear we are calling attention to the uneven change of events over time, and the disproportionate responses that systems make when we try to affect or control them in some manner. Sometimes a small intervention has a dramatic impact. Sometimes a large plan accomplishes very little.

THE RISE AND FALL OF BUREAUCRACY

NDS’s contributions to organizational theory are best appreciated against a backdrop of the previous major landmarks in organizational science. Less than a century ago, bureaucracy was considered an improvement over the way organizations had been managed previously (Weber, 1946). Bureaucracy meant that there was a division of labor. Each member of the organization performed tasks that began somewhere and ended somewhere else. The ambiguity regarding who was responsible for what was, in principle, extricated.

Bureaucracies assigned clear responsibility for decisions to job roles. By making clear assignments, it was possible to make decisions efficiently within the boundaries of policies that were set by people in other job roles. The definition of policies for the use by other organizational members removed the necessity of restating a policy every time an example of a decision had to be made. It also produced a hierarchical structure.

The nature of a role meant that there was a disconnection between the set of actions denoted by the role and the human being who was incumbent in that role. This disconnection was thought to ensure that decisions were results of policy rather than individual whim, nepotism, or other kinds of organizational politics. The system of roles would also provide equal treatment of personnel and clients. Bureaucracy delivered on its expectations to a great extent, although the extrication of politics from organizations was a fantasy. There were human costs to this efficiency as well.

Bureaucracy and its system of roles were based on a value for rationality. Rationality was the basis of efficiency, and was in turn based on an assumption of a mechanistic system. We are thus confronted with some glaring psychological questions:What is rationality? What is irrationality? Is one always better than the other? Why do we think so? Why do bureaucracies occasionally produce irrational or counterproductive results?

The beginnings of two long answers to the foregoing questions first appeared in the 1950s. One response was that of bounded rationality, whichstates that humans can only process so much information well, and beyond that point we should not expect much more in the way of rationality. The artificial intelligence movement tried to plug the holes in human rationality.

The other response to the gap in bureaucratic rationality was the humanization movement. People have feelings, emotional reactions, and personalities, none of which are going to disappear through any act of management. Rather, it is the not-traditionally-rational aspects of human nature that are critical to great accomplishments. Emotional reactions can be rational responses to irrational situations. As a result, more of an organization’s objectives can be accomplished with less managerial command and control, rather than more. The nature of bounded rationality, contributions of artificial intelligence, and humanization approaches to organizational management are unpacked in later chapters.

The structure of bureaucracy and the liquidity of humanization eventually melted together into what might be called organic forms of organizations. Now there was an awareness that a work organization was a life form, rather than a machine. The organization was still driven by its rationality, but it was kept alive by its subrational verve.

In the wave of thinking that culminated in the late 1990s, the organization is a complex adaptive system, which recognized nonlinear patterns of behavior (Anderson, 1999; Dooley, 1997; Guastello, 1995a). Now that organizations are recognized as being alive, we can proceed to questions regarding how they stay that way. How does an organization interpret signals and events in its environment? More importantly, how does it utilize the events in its environment to its own benefit? How does it harness its capabilities as a living system to make effective responses? How and when does it change itself from one form to another in order to enhance its viability as a big collective living organism? How is it affected by other organizational life forms?

Conventional psychology and organizational science have tackled these questions to some extent. Much more is left to NDS, which has produced new knowledge about organizations. Ultimately, the objective of the following chapters is to produce a viable theory of organizations that integrates NDS principles with the best findings from other sources.

ENTER THE HOUSE OF PANIC

A city is a complex system. Every morning people roll out of bed, run some water, jump into some clothes, and head off to work. Trucks and horse-drawn carts make deliveries and fight for parking spaces. Switches turn on. The block smells like bread and pastry—or maybe it’s the smell of the brewery getting started for the day. The sky is still dark.

A newspaper editor and a reporter slurp coffee. They were up most of the night finishing a story that seemed important. It was too late to go to bed and wake up again, so they just stayed up. They wisecracked about something you had to be there to appreciate. A vibration rattled coffee cups that no one was touching. Waitresses disappeared. The editor and the reporter stifled their jokes in midsyllable.

Over the previous 50 years, the 400,000 residents of San Francisco had become used to ground tremors that would have terrorized the tourists. Citizens had once debated whether wood frame houses were safer than brick and steel structures. Their preferences eventually leaned toward brick and steel. The post office had recently built an elaborate new facility on land that was reclaimed from the nearby water. Hills around the city were lowered to bring a vast low-lying area above sea level. Some street level building entrances became subcellars while other became third story windows as a result of the regrading. The city’s gas and water lines were set in pathways of reclaimed ground, which some people characterized as “jelly.”

The city had grown to 10 times its original size during the gold rush of 1849 and shortly afterward. The luck of the prospectors, and the instability that went with it, generated an economy that centered on living in the present and living well whenever possible. The lives and futures of San Franciscans were less predictable than lives in other cities of that era, but for many the slim chance of something great happening was a step up from the certainty of going nowhere. San Francisco was a vibrant center for worldwide immigration. By 1906 it had amassed the largest population of Chinese outside of China itself. The occasional devastation from earthquakes and the steady growth of a luckless and unemployed population contributed to the mentality of living in the present.

Farmers and merchants eventually followed, mostly from the Eastern direction. The land supported large and successful crops of fruits and vegetables. Some people amassed great wealth and channeled it into fine real estate, social development, and institutions of art, science, and higher education. Perhaps the transition toward stable architecture was as much a reflection of the growing stability of the society as it was the result of lessons learned from the quakes.

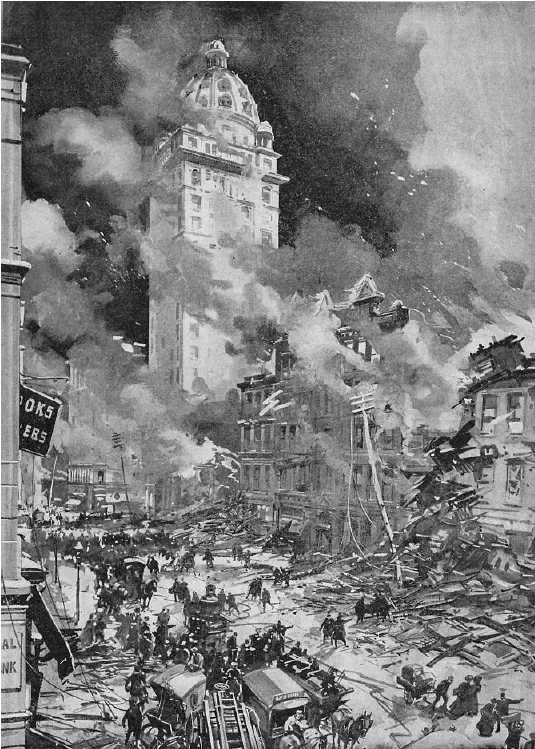

The tremors permeated the region and lasted nearly 3 minutes. During those 3 minutes the earth opened its mouth and swallowed large sections of San Francisco, and continued to do so over the next week as the tremors returned in 30-second bursts at irregular intervals. By all accounts, the greatest damage was caused by fires, which raged instantly all over the city. The ruptured gas lines fueled they fires, which fed on themselves as they spread. In the early hours of the disaster, the fire response was able to pump water from the harbor to quell the fires closest to the water. The water could not be pumped nearly as far as it was needed, or to nearly as many locations; the water lines around the city were instantly ruptured along with the gas lines.

Figure 1.1 is a scene from Market Street that was depicted in a photograph (from Morris, 1906). People evacuated themselves as best as they could with no motorized transportation. Frame buildings crashed around them. “Mr. J. P. Anthony, as he fled from the Ramona Hotel, saw a score or more people crushed to death, and as he walked the streets at a later hour saw bodies of the dead being carried in garbage wagons and all kinds of vehicles to the improvised morgues, while hospitals and storerooms were already filled with the injured” (Morris, 1906, p. 115). Other eyewitnesses gave reports that were every bit as gruesome.

The tall white building furthest from the camera in Fig. 1.1 was comparatively unscathed, as were the post office, the mint, and customs house. The telegraph facility in the post office turned out to be a crucial link to the outside world along with newspapers and reporters who moved their base of operations to Oakland during the crisis. City Hall, on the other hand, was a total loss.

Municipal fire fighters quickly determined that they were unable to control the spread of the fires by conventional means, and the path of the fire indicated that the devastation was only going get worse in a hurry. Fortunately, Mayor Eugene Schmitz made contact with General Funston at the nearby Presidio. Funston responded with a team of demolition experts who were able to control the spread of the fire by blowing up blocks of buildings that lay in the path of the spreading fire. Figure 1.2 is a portrait of Mayor Schmitz. The original caption read: “Mayor Schmitz, by his untiring efforts and great executive ability, brought order out of chaos” (Morris, 1906, p. 104).

The tourists, who were staying at the hotels, were the first to pack their belongings and leave if they could do so. Their first response was to head for the harbor to catch a ferry to Oakland. The ferry could only accommodate a small number of people at a time.

FIG. 1.1. San Francisco under siege from earthquake and fire. Reprinted from Morris (1906). In the public domain.

FIG. 1.2. Mayor Eugene Schmitz of San Francisco. Reprinted from Morris (1906). In the public domain.

Citizens who survived responded first by securing their own lives, those of their families and neighbors, and their homes. The shock of the disaster drove some people insane, and they too had to be counted as casualties. Disaster relief teams suddenly appeared. There is no clear record of exactly how they appeared. Some were outgrowths of civic organizations that were already organized. Others emerged for the occasion. The police and military conscripted any freely roaming men to the nearest rubble pile to dig out survivors.

The maintenance of law and order was given a high priority and a clear enforcement policy. The military and the police were under orders to shoot looters on sight. In the early days of the ordinance, common citizens were also given the power to terminate looters. It soon became apparent, however, that the citizens had little skill in law enforcement and that they had coagulated into lynch mobs. The revised directive assigned all execution powers to the police or military.

The criminal challenge was at least as formidable as the other challenges of the situation. One team of bandits was apprehended while trying to break into the mint. An eyewitness discovered the body of a woman in a hotel’s wreckage. A looter who wanted the gem stone it must have held had amputated her ring finger. It was unclear whether she was already dead or just unconscious when her finger was cut off. In spite of the best intentions of the police and military, mistakes were still made. People who were rummaging through what was left of their own homes were unfortunately shot as looters too.

Food was scarce. A loaf of bread, if a store was lucky enough to still have one, sold for 20 times the usual price. Again, police intervened to liberate food supplies for the starving. As soon as news of the earthquake escaped the city, food and medical supplies poured in from sources all over the United States and Canada. Businesses with headquarters in foreign countries made contributions as well. City parks were turned into lodging for the homeless and food distributions centers (Fig. 1.3).

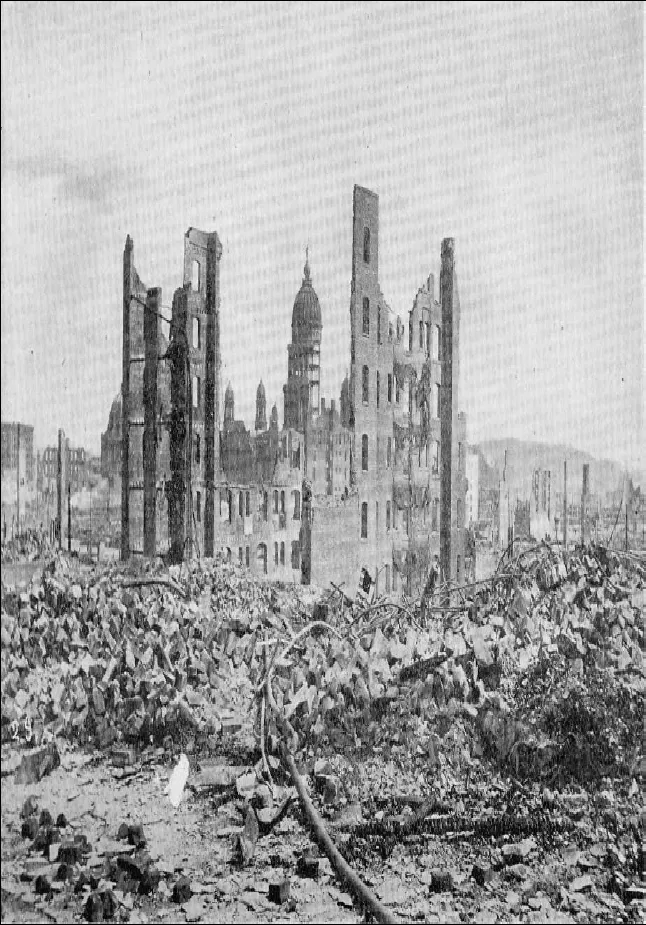

The reconstruction of the city was an equally formidable task, and one that required a very different set of management requirements. Figure 1.4 is a view of what was left of Van Ness Avenue. The shell of city hall appears in the distance. Fortunately, Mayor Schmitz was successful in framing attractive offers to architects, engineers, and other professionals of exceptional talent who poured into the city region to rebuild its physical presence and social fabric.

PRINCIPLES OF NONLINEAR DYNAMICS, CHAOS, AND COMPLEXITY

The foregoing tale of the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 captures a number of issues that face managers and social architects in less dramatic, but more widespread, circumstances. NDS is a general systems theory, which means that it contains general principles that describe and predict events that are very different in their obvious appearances. Parallels inevitably exist between the functioning of business organizations nonhuman ecology, biological structures, and other collectives of humans or animals that form around different objectives. General systems thinking (e.g., Miller, 1978; L. von Bertalanffy, 1968) thus identifies common themes regarding the behavior of living systems and for generating explanations for phenomena that had not been forthcoming through the conventional analysis of localized problems.

FIG. 1.3. Care for the homeless of San Francisco in the aftermath of the earthquake. Reprinted from Morris (1906). In the public domain.

FIG. 1.4. Ruins of San Francisco. Reprinted from Morris (1906). In the public domain.

General systems theories often begin, or culminate, in relationships that can be mathematically defined. Some theorists emphasize the mathematical content more than others do, depending on what they are trying to accomplish. NDS is clearly of mathematical origin. Fortunately, however, we will use the products of its mathematics in our study of organizations. The products take the form of relationships that we can describe in pictures. The specialized math promotes the analysis of data that we observe in the laboratory or in real-world situations. In other words, we can test our claims in a scientific manner that can tell us whether our specific principles of dynamics apply to the situations we are trying to study.

Principles of Elementary Dynamics

NDS’s central principles can be grouped into those that pertain to elementary dynamics, and those the address complex systems and emergent phenomena. The elementary dynamics include the particular phenomenon of chaos, which gave rise to the name “chaos theory.” The second group, which is usually invoked under the rubric of “complexity theory,” cannot be fully appreciated without elementary dynamics.

The consensus today is that the subject matter of NDS can be traced to the pivotal work of Henri Poincaré, a mathematician from the 1890s. His study of astrophysical dynamical processes produced the first observation of mathematical chaos on the one hand, and a highly visual approach to mathematics on the other. Many of the topologies that he studied were so complex that it was not possible to write equations for them. It was not until the development of differential topology that it was possible to fill in this major gap.

Poincaré’s phenomena did not have a cute name, like “chaos.” Mathematicians did not revisit this group of phenomena until the early 1960s, when Lorenz, a meteorologist, drew our attention to the strange attractor. Li and Yorke (1975) introduced “chaos” into the general systems vocabulary; the formal definitions of chaos and other key terms will be saved for the next chapter. In any case, we arrive at the first two principles:

1. Many seemingly random events are actually the result of deterministic processes that we can describe using simple equations. It is no small trick to find the equations.

2. Small differences in the initial conditions of a situation can evolve into radically different system states later on in time.

The next NDS principle pertains to catastrophes. Catastrophes are sudden and discontinuous changes in events. The underlying math and the original exposition about how they can be used is attributed to René Thom (1975). Many of the first applications in the social sciences are credited to E. C. Zeeman (1977).

3. All discon...