- 313 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Yezidi Oral Tradition in Iraqi Kurdistan

About this book

The Yezidis are a Kurdish-speaking religious minority, neither Muslim, Christian nor Jewish. Their ethnicity has been disputed, but most now claim Kurdish identity. Their heartland, including their holiest shrine, is in the Badinan province of Northern Iraq, and it is the communities in this area which are the main focus of this book. Their highly

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Yezidi Oral Tradition in Iraqi Kurdistan by Christine Allison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

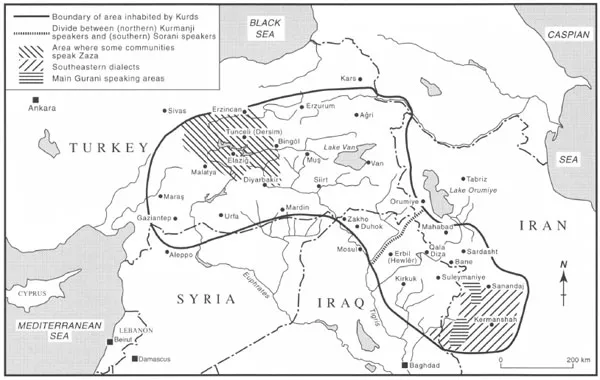

Map 1: Areas inhabited by Kurds

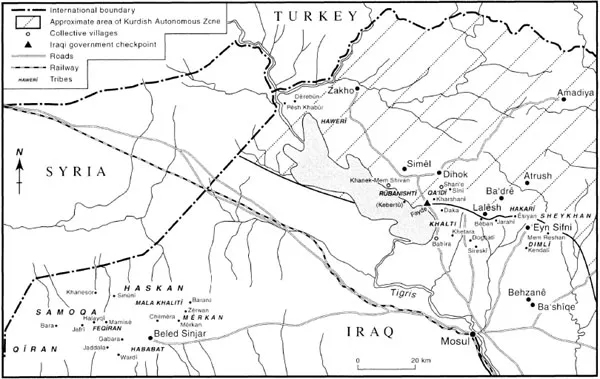

Map 2: Yezidi communities in Northern Iraq: Badinan and Sinjar

Chapter One

Interpreting Yezidi Oral Tradition: Orality in Kurmanji and Fieldwork in Kurdistan

Introduction

For centuries Orientalists have been fascinated by the Yezidis of Kurdistan and their curious religion. A great deal has been written, much of it speculative, about their origins, their beliefs and their more arcane practices. Both Oriental and Western scholars and travellers of the past, conditioned by contact with ‘religions of the Book’, usually came to the Yezidis with a preconceived scheme of religious categories in their minds, into which they sought to fit the Yezidis. The Yezidis’ answers were determined by the researchers’ questions, and where entire Yezidi accounts of events or beliefs were collected, these were not interpreted in the light of the Yezidis’ world-view, but according to the researchers’ own preconceptions. Until the recent emergence of an educated younger generation, they only reached a reading public at second hand, via others’ descriptions. As a result, the Yezidis became one of the more misunderstood groups of the Middle East, the exotic ‘devil-worshippers of Kurdistan’.

Within the last generation there has been a move towards a fuller study of the Yezidis’ own discourses. This has partly been done through ethnography (al-Jabiri 1981, Murad 1993, Ahmad 1975) but also by means of considering their religious ‘texts’ as examples of oral tradition (Kreyenbroek 1995). Oral tradition is crucially important for the Yezidis, as amongst their many religious taboos was a traditional ban on literacy. They communicated with their neighbours, and passed on their community history, literature, wisdom and religious texts to their descendants, orally. There is an intimate relationship between the spoken forms and methods of transmission of this oral material and its content. This book seeks to analyse the way this community, so often described by outsiders, describes the key subjects of war, love and death through oral tradition, the only form of literature available to the entire community. These traditions are intimately related to the Yezidis’ perception of their own identity.

This is not the first study of Yezidi oral ‘texts’; academic understanding of the religion has advanced considerably through recent publications on Yezidi cosmogonies, and on the orally transmitted sacred hymns or qewls and their place in the religion (Kreyenbroek 1992, 1995). However, it is the first study of Yezidi, and indeed of Kurdish, secular oral traditions within their social context. Although this book concentrates on secular oral tradition, it should be emphasised that, since Yezidism is a religion of orthopraxy, practising Yezidis are living out their religion in their everyday life; every aspect of the traditional life is associated with taboos, observances or devotions. Thus even those secular oral traditions which will be discussed here contain many allusions to Yezidi religious themes, and should not be divorced from their religious context. The traditions under consideration in this book are historical, that is, they are generally believed to be about real individuals who lived in the past. The performances of oral literature in which they are couched are not only a major source of factual knowledge of the past for Yezidis, but for the outsider their analysis can also yield a great deal of information, not only about Yezidi aesthetics and poetics, but also about their current preoccupations. What the Yezidis choose to tell, or to withhold, about the past, reveals much about their present attitudes.

This study, then, hopes to come closer to the Yezidis’ identity than the approaches of the older Orientalists, though, as the work of an outsider, it cannot claim to understand the community’s comment on itself at every level. It is fully appreciated that the concept of ‘social context’ is itself ethnocentric; which social and cultural elements are emphasised and which ignored are at the discretion of the researcher. For reasons of space, this study cannot discuss every single form of oral tradition used by the Yezidis, and it is a matter of particular regret that the music of the traditions will not be analysed. Nevertheless, the material presented here has never before been the subject of academic study, and those few traditions which I will discuss in detail are certainly considered by the Yezidis to be important. Since not only the content of the traditions, but also the forms used, the modes of transmission and, wherever possible, the styles of performance will be considered, it is hoped that this work will be a starting-point for new methodologies in Kurdish studies. No study can be fully objective; later in this chapter I shall declare my own preconceptions as far as possible by outlining the methodologies to be used.

The Yezidi community in Northern Iraq lends itself particularly to this type of study. They are a discrete community among other groups, but their religious and social structure ensures a degree of social and cultural uniformity which, given the variety of cultures found in Kurdistan, is greater than might be expected from a group spread over an area stretching from Jebel Sinjar to ʿAqra in Iraq. During fieldwork, done between March and mid-October 1992 in the area of Northern Iraq controlled by the Kurds, Yezidi informants claimed that the important stories were uniform throughout the community as they represented the ‘true’ and distinctive Yezidi history. However, this book will not only present material collected during fieldwork. Published collections of Kurdish ‘folklore’ have included Yezidi material collected in Armenia and Syria earlier this century and in Badinan and Jezîre Botan at the end of the nineteenth century; these offer opportunity for comparative study, and have been used accordingly.

The Yezidis of Northern Iraq, with the exception of a few Arabic speaking villages, have Kurmanji Kurdish as their mother-tongue, and their oral traditions include a great deal of material describing past events in what is now Eastern Turkey. Despite their notions of separateness, they have never been a community in isolation from the rest of Kurdish tribal politics. Some of the observations one can make about Yezidi discourses also hold good for those of other Kurdish groups, and before we can describe the special nature of Yezidi orality (which will be discussed in the next chapter), we must place the Yezidis in sociolinguistic context, by discussing what ‘orality’ and ‘literacy’ mean, and how they apply, in the context of Kurmanji. It will then be necessary to contextualise this work, by outlining its relationship to past studies of Kurmanji material, its theoretical stance within the multidisciplinary field of oral studies, and the fieldwork environment which influenced the methodologies used.

The Kurmanji Context

It is unfortunate that despite a number of very useful studies of Near and Middle Eastern oral poetry and folktales (e.g. Slyomovics 1987, Muhawi 1989, Reynolds 1995), and a few outstanding accounts of the role of oral traditions within certain groups (e.g. Abu Lughod 1988, Grima 1992, Mills 1990, Shryock 1997), oral traditions remain irrevocably associated in many academic minds with ‘folklore’ in its most pejorative sense, with picturesque but obsolete customs and spurious accounts of the past. This is a narrow and outmoded view of both oral tradition and folklore, of which oral tradition forms a part. With some honourable exceptions, scholars of the Near and Middle East lag behind those working on other regions, notably Africa, in their appreciation of the political dimensions of oral tradition. Orientalists in general seem to show a reluctance to move on from their perception of ‘folklore studies’ as merely a matter of classically inspired oral-formulaic analyses of reassuringly obscure and irrelevant genres. Yet in the authoritarian states of the Near and Middle East, where written material is rigorously censored, points of view which contradict the government are usually by necessity expressed orally. Oral communication is often the vehicle of minority discourses, of tendencies deemed to be subversive; oral tradition, with its hallowed accounts of the people’s past, provides a whole fund of folkloric examples which can be used to justify political courses of action, to rouse a rabble, or to fuel a revolution. During the 1990s, the Newroz myth of the Iranian New Year (as told in Kurdish tradition rather than the Persian version of the Shah-name) was used as a symbol of Kurdish liberation in Turkey, sparking widespread unrest in towns and cities every March. Governments also use folklore in their own propaganda; Turkey, for instance, claims Nasruddin Hoca as its own, though he is found in the traditions of many countries in the region (Marzolph 1998). Oral tradition, along with other aspects of folklore, is an important element in discourses of nationalism and of identity all over the modern Middle East; Kurdistan is not exceptional in this respect, though circumstances have conspired to make Kurmanji in particular more ‘oral’ and less ‘literary’ than many other languages of the region.

Despite the long tradition of Kurdish scholars and authors, many of whom used Arabic, Persian or Turkish as well as Kurdish in their writings, the great majority of Kurds in the past have not been literate enough to be able to read ‘literature’. Kurmanji, the northern dialect of Kurdish, is spoken by Kurds living in Eastern Turkey, Northern Iraq, Northern Syria, Iran, and Transcaucasia. It is the dialect of the first Kurdish written literature, the works of Melayê Jezîrî and Ehmedê Khanî,1 and is spoken by more people than the other major dialect, Sorani. However, its influence has been lessened in the twentieth century by government repression of the language in those states where Kurds live. In the last years of the Ottoman empire, literacy overall must have been relatively low among the Kurmanji speakers of Eastern Anatolia by comparison with other provinces.2 Kurdish had not hitherto been proscribed, but in the new Republic of Turkey it was outlawed in the 1920s, beginning with its prohibition for all official purposes in 1924. Even education in Turkish was out of the question for most Kurds at this time; only 215 of the 4,875 schools in Turkey were located in Kurdish areas (MacDowall 1996: 192). Educational opportunities in Eastern Anatolia grew far more slowly than those elsewhere in Turkey as the century passed, but what State education was available was in Turkish. Education in Kurmanji was never officially permitted; this situation continues today. Not only were publication and broadcast in Kurmanji forbidden for most of the twentieth century, but at times of greatest repression Kurds could be fined, or otherwise punished, for speaking the language. Along with the renaming of Kurds as ‘mountain Turks’ came spurious classification of Kurmanji as a deviant Turkish language (e.g. Firat 1961). With the exception of a few years during the 1960s, and the years since 1991 when Kurmanji was once more ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Map 1: Areas inhabited by Kurds

- Part I

- Part II: Kurdish Texts and Translations

- Notes to Chapters 1–6

- Appendix: Informants and Performers

- Bibliography

- Index