eBook - ePub

Food Packaging

Advanced Materials, Technologies, and Innovations

- 394 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Food Packaging

Advanced Materials, Technologies, and Innovations

About this book

Food Packaging: Advanced Materials, Technologies, and Innovations is a one-stop reference for packaging materials researchers working across various industries. With chapters written by leading international researchers from industry, academia, government, and private research institutions, this book offers a broad view of important developments in food packaging.

- Presents an extensive survey of food packaging materials and modern technologies

- Demonstrates the potential of various materials for use in demanding applications

- Discusses the use of polymers, composites, nanotechnology, hybrid materials, coatings, wood-based, and other materials in packaging

- Describes biodegradable packaging, antimicrobial studies, and environmental issues related to packaging materials

- Offers current status, trends, opportunities, and future directions

Aimed at advanced students, research scholars, and professionals in food packaging development, this application-oriented book will help expand the reader's knowledge of advanced materials and their use of innovation in food packaging.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Food Packaging by Sanjay Mavinkere Rangappa, Jyotishkumar Parameswaranpillai, Senthil Muthu Kumar Thiagamani, Senthilkumar Krishnasamy, Suchart Siengchin, Sanjay Mavinkere Rangappa,Jyotishkumar Parameswaranpillai,Senthil Muthu Kumar Thiagamani,Senthilkumar Krishnasamy,Suchart Siengchin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Physics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Bio-Based Materials for Active Food Packaging

Dream or Reality

Ângelo Luís, Fernanda Domingues, and Filomena Silva

Contents

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Active Food Packaging: General Definitions and Some Examples

1.2.1 Antioxidant Packaging

1.2.2 Water Absorbers/Scavengers

1.2.3 Ethylene Scavengers/Absorbers

1.2.4 Antimicrobial Packaging

1.3 European Directive on Circular Economy: The Change from Plastics to Bio-Based Materials

1.4 Bio-Based Packaging Materials: Obtention of Materials Commercially Available and Their Degradation Path

1.4.1 Polysaccharides

1.4.1.1 Starch

1.4.1.2 Agar

1.4.1.3 Alginate

1.4.1.4 Chitin/Chitosan

1.4.1.5 Xanthan Gum

1.4.1.6 Xylans

1.4.1.7 Pullulan

1.4.1.8 Carrageenan

1.4.1.9 Pectin

1.4.1.10 Cellulose-Derived

1.4.2 Proteins

1.4.2.1 Whey

1.4.2.2 Casein

1.4.2.3 Zein

1.4.2.4 Gelatin

1.4.3 Flour-Based

1.5 Bio-Based Active Packaging Materals: Focus on Examples Tested In Vivo

1.5.1 Chitosan-Based Active Packaging Materials

1.5.2 Cellulose and Cellulose-Based Packaging Materials

1.5.3 Gelatin-Based Packaging Materials

1.5.4 Starch-Based Packaging Materials

1.5.5 Other Protein-Based Packaging Materials

1.5.6 Alginate-Based Packaging Materials

1.5.7 Other Bio-Based Active Packaging

1.6 Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

1.1 Introduction

The use of plastic packaging is on the rise, explained by the need to reduce food waste and the increased demand due to population growth and market expansion (Groh et al., 2019; Narancic and O’Connor, 2019). However, there are also increasing concerns about the damage caused to the environment and human health (Groh et al., 2019; Narancic and O’Connor, 2019). These concerns include littering and accumulation of nondegradable plastics in the environment (Andrady, 2011), generation of secondary micro- and nano-plastics (Hernandez et al., 2019), and release of hazardous chemicals during manufacturing and use, as well as following landfilling, incineration, or improper disposal leading to pollution of the environment (Groh et al., 2019; Narancic and O’Connor, 2019).

Advances in food packaging have played a vital role across the world (Marsh and Bugusu, 2007). Simply stated, packaging maintains the benefits of food processing after the process is completed, enabling foods to travel safely for long distances from their point of origin and still be wholesome at the time of consumption (Lee et al., 2015; Sohail, Sun, and Zhu, 2018). However, packaging technology must balance food protection with other issues, including energy and material costs, heightened social and environmental consciousness, and strict regulations on pollutants and disposal of solid waste (Marsh and Bugusu, 2007).

Among developed countries, the European Union (EU) has the strictest arsenal of rules. “EU Framework Regulation 1935/2004/EC” makes risk assessment and risk management compulsory for the introduction of any new substance, material, or industrial practice (active/intelligent packaging system, recycling) regardless of whether the material is plastic or not (Zhu, Guillemat, and Vitrac, 2019). While not mentioning design, “EU Regulation 2023/2006/EC” encourages the developments of good manufacturing practices and quality assurance systems at all stages of production and handling for each of the 17 groups of materials and their combinations accepted for food contact (Zhu, Guillemat, and Vitrac, 2019). The reduction of the environmental impact of packaging and its wastes has been enforced in the EU for the past 25 years via the “Directive 94/62/EC” (Zhu, Guillemat, and Vitrac, 2019).

New packaging systems are an effective way to extend and/or maintain the shelf life of foods and to preserve the quality of a range of fresh products such as vegetables, fruits, meat, and fish (Lee et al., 2015; Janjarasskul and Suppakul, 2018). Active packaging (AP) systems have been developed by the food industry, and their effectiveness in extending the shelf life of fresh foods has been reported in several studies (Lee et al., 2015; Janjarasskul and Suppakul, 2018; Al-Tayyar, Youssef, and Al-hindi, 2020). For example, active packaging inhibits microbial contamination and spoilage in fresh foods by employing antimicrobial packaging materials or gaseous agents or antimicrobial inserts in the package headspace (Lee et al., 2015; Janjarasskul and Suppakul, 2018; Pellerito et al., 2018).

Polymer biocomposites are novel materials that have gained increased interest from researchers in polymer science and engineering, since they are novel, high-performance, lightweight, and eco-friendly materials that can replace traditional nonbiodegradable plastic packaging (Al-Tayyar, Youssef, and Al-hindi, 2020).

Therefore, the major aim of this chapter is to make an overview of bio-based materials for active food packaging keeping also in mind the circular economy and the degradation path of these materials.

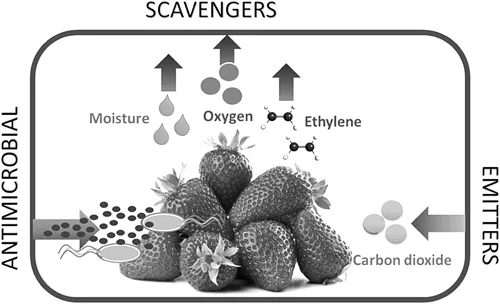

1.2 Active Food Packaging: General Definitions and Some Examples

Food packaging, in a broad sense, refers to the barrier that protects food products from environmental disturbances such as oxygen, moisture, light, dust, chemical, and microbiological contamination. At its beginnings, packaging materials were inert polymers made of cardboard, glass, and, ultimately, plastic that only served this protection purpose; but over the years, packaging has evolved to incorporate technologies such as vacuum (VP) and modified atmosphere packaging (MAP). These technologies have long been used to maintain product freshness and increase its shelf life by controlling the gas atmosphere of the packaged food, delaying oxygen-dependent processes such as food oxidation and microbial growth. Despite the success attained by such technologies, the food industry still requires newer and better performing technologies to decrease food losses and extend even further the shelf life of packaged products, which resulted in the introduction of active packaging. According to “European Regulation (EC) No 450/2009,” active packaging systems “deliberately incorporate components that would release or absorb substances into or from the packaged food or the environment surrounding the food” (European Commission, 2009). In general, active packaging systems can be divided into two main groups: absorbers (active scavenging systems) and emitters (active-releasing systems) (Yildirim et al., 2018) (see Figure 1.1).

Furthermore, AP can be divided according to the main problem they are supposed to tackle in the food product, such as oxidation (antioxidant packaging), microbial growth (antimicrobial packaging), increased moisture (moisture absorber) and ripening control (ethylene absorber) (see Table 1.1).

TABLE 1.1

Types of Active Packaging and Examples of Strategies Used

Types of Active Packaging and Examples of Strategies Used

1.2.1 Antioxidant Packaging

Antioxidant compounds can be divided into two groups according to their function: primary or chain breaking antioxidants and secondary or preventive antioxidants (Mishra and Bisht, 2011). Primary antioxidants can accept free radicals (e.g., lipid or peroxyl radicals) leading to the delay of autooxidation initiation or the interruption of its propagation by converting free radicals to stable radicals or non-radical products usually through the donation of hydrogen atoms (Mishra and Bisht, 2011). In contrast, secondary antioxidants act by preventing oxidation processes by a variety of routes such as binding transition metal ions, scavenging oxygen, replenishing hydrogen atoms to primary antioxidants, absorbing UV light and inhibiting oxidizing enzymes (Silva, Becerril, and Nerin, 2019). For instance, phenolic compounds and hydroxylamines act as multi-functional antioxidants (Ambrogi et al., 2017) as they can function either as primary or secondary antioxidants through different mechanisms (Mishra and Bisht, 2011). In terms of antioxidant packaging (AOXP) technologies, the two main types available are oxygen scavengers/absorbers and free radical scavengers. Oxygen absorbers react with the oxygen in the packaging atmosphere, ceasing its action on the food product. The most widely used oxygen scavenger is ferrous oxide although there are other compounds available such as catechols, ascorbic acid, sulfites, and enzymes such as glucose oxidase or catalase (Nerin, Vera, and Canellas, 2018; Kerry, O’Grady, and Hogan, 2006). Free radical scavengers such as synthetic ones like selenium nanoparticles, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) or natural ones such as plant extracts and essential oils react with free radicals so that they are unable to engage in further oxidative chain reactions. Over the years, AOXP has evolved from using synthetic antioxidants incorporated in plastic materials such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET) or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) to using natural antioxidants incorporated in the same plastic materials and, finally, the most recent tendency is the incorporation of natural antioxidants (green tea, olive leaf extracts, resveratrol, alpha-tocopherol, essential oils, etc.) in more eco-friendly and sustainable materials such as bioplastics (e.g., poly(lactic acid)) and biopolymers (starch, protein, chitosan, etc.). These packages with antioxidant properties have been applied to a vast array of food products that are susceptible to oxidation such as fatty foods (peanuts, cereals, butter, oils), meat (beef, pork, chicken), fish and vegetables (mushrooms) (for a more detailed review, please refer to Silva, Becerril, and Nerin (2019).

1.2.2 Water Absorbers/Scavengers

Although moisture control can be achieved with modified atmosphere and vacuum packaging and the use of low barrier polymers (micro-perforated films, enhanced permeability films), only the use of desiccants or absorbers can be designated as active moisture packaging. Other strategies are known as passive moisture packaging (Yild...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Editors

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Bio-Based Materials for Active Food Packaging: Dream or Reality

- Chapter 2 Biodegradable Films for Food Packaging

- Chapter 3 Recent Advances in the Production of Multilayer Biodegradable Films

- Chapter 4 Environmental Issues Related to Packaging Materials

- Chapter 5 Antimicrobial Studies on Food Packaging Materials

- Chapter 6 Biodegradable Eco-Friendly Packaging and Coatings Incorporated of Natural Active Compounds

- Chapter 7 Biodegradable Polymer Composites with Reinforced Natural Fibers for Packaging Materials

- Chapter 8 Electrospun Nanofibers: Fundamentals, Food Packaging Technology, and Safety

- Chapter 9 Influence of Nanoparticles on the Shelf Life of Food in Packaging Materials

- Chapter 10 Optoelectronic and Electronic Packaging Materials and Their Properties

- Chapter 11 Processing and Properties of Chitosan and/or Chitin Biocomposites for Food Packaging

- Chapter 12 Chitosan-Based Hybrid Nanocomposites for Food Packaging Applications

- Chapter 13 Medium Density Fiberboard as Food Contact Material : A Proposed Methodology for Safety Evaluation from the Food Contact Point of View

- Chapter 14 Applications of Nanotechnology in Food Packaging

- Index