Social Change in Japan, 1989-2019

Social Status, Social Consciousness, Attitudes and Values

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Social Change in Japan, 1989-2019

Social Status, Social Consciousness, Attitudes and Values

About this book

Based on extensive survey data, this book examines how the population of Japan has experienced and processed three decades of rapid social change from the highly egalitarian high growth economy of the 1980s to the economically stagnating and demographically shrinking gap society of the 2010s. It discusses social attitudes and values towards, for example, work, gender roles, family, welfare and politics, highlighting certain subgroups which have been particularly affected by societal changes. It explores social consciousness and concludes that although many Japanese people identify as middle class, their reasons for doing so have changed over time, with the result that the optimistic view prevailing in the 1980s, confident of upward mobility, has been replaced by people having a much more realistic view of their social status.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

Deciphering the “middle”

Subtle change behind the scenes

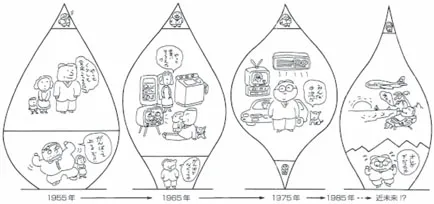

2 Images of social stratification and the “Gap Society”1

1 Considering society from the “shape of society”

1.1 What is the shape of society?

1.2 Reasons to explore the shape of society

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Introduction

- Part I Deciphering the “middle”: subtle change behind the scenes

- Part II Adapting to change: social consciousness over the Heisei period

- Index