International Perspectives on Digital Media and Early Literacy

The Impact of Digital Devices on Learning, Language Acquisition and Social Interaction

- 198 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

International Perspectives on Digital Media and Early Literacy

The Impact of Digital Devices on Learning, Language Acquisition and Social Interaction

About this book

International Perspectives on Digital Media and Early Literacy evaluates the use and impact of digital devices for social interaction, language acquisition, and early literacy. It explores the role of interactive mediation as a tool for using digital media and provides empirical examples of best practice for digital media targeting language teaching and learning.

The book brings together a range of international contributions and discusses the increasing trend of digitalization as an additional resource in early childhood literacy. It provides a broad insight into current research on the potential of digital media in inclusive settings by integrating multiple perspectives from different scientific fields: (psycho)linguistics, cognitive science, language didactics, developmental psychology, technology development, and human–machine interaction. Drawing on a large body of research, it shows that crucial early experiences in communication and social learning are the basis for later academic skills. The book is structured to display children's first developmental steps in learning in interaction with digital media and highlight various domains of early digital media use in family, kindergarten, and primary schools.

This book will appeal to practitioners, academics, researchers, and students with an interest in early education, literacy education, digital education, the sociology of digital culture and social interaction, school reform, and teacher education.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part 1

Learning and interaction with digital devices

Chapter 1

Promising interactive functions in digital storybooks for young children

Introduction

Digital storybooks version 2.0

Interactivity in first-generation digital books

Theory and principles of interactivity in 2.0 digital books

Multimedia learning theories

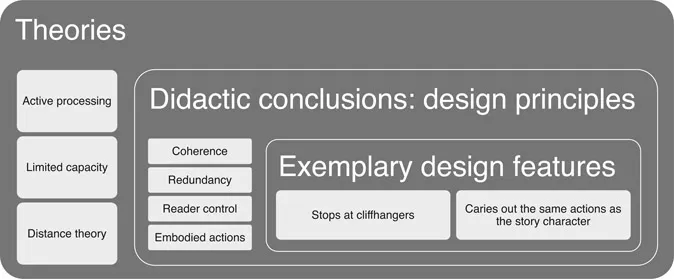

- Active processing: Humans are not passive processors who seek to add as much information as possible to memory (Mayer, 2005a). They are active processors who seek to make sense of new information. This typically includes paying attention, selecting from all incoming information, and integrating information with their prior knowledge (Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1997). The child applies cognitive processes to incoming narrative and other information to make sense of the storyline (Glenberg, Gutierrez, Levin, Japuntich, & Kaschak, 2004). We do not want children to lean back and listen; we want them to actively make attempts to interpret the presented information – the main reason to add interactive functions. Interactivity is a strength of digital media that, if intertwined with a narrative, may be a strong tool to promote effective problem solving.

- Capacity theory: However, the interactive embedded content may come at a cost for performance. Because the human information processing system has a limited capacity, distributing cognitive resources across both the narrative and the embedded content may be problematic. A person’s ability to process both simultaneously depends on how much capacity separate sources require. Adverse outcomes may result from limited resources being available for processing both narrative and embedded content (Kahneman, 1973). When the embedded content is tangential to the narrative, the two parallel processes of comprehension compete for limited resources in working memory. The result may be that the narrative cannot be processed as deeply as it might otherwise be, and that children may attend to only part of it, thus potentially distorting understanding of the narrative content and resulting in less detailed representations (Yokota & Teale, 2014).

- Distance theory: However, outcomes may be different when interactive functions are intertwined with the narrative. By studying educational television content, Fisch (2000) introduced the idea that distance between the narrative and embedded content will contribute to clear-cut distinctions between problematic and promising embedded content, suggesting that if the distance between the narrative and the embedded content in digital books is small, these elements can complement one another rather than compete for resources, thereby functioning to increase meaning-making of the narrative.

Do’s and don’ts of interactive quality design

- Coherence principle: It is important that children are involved only in the interactive functions striking the very core of the narrative, and that we bypass interactive functions related only to story themes that would risk introducing extraneous material that might distract children from the storyline. For instance, we may expect adverse effects on story comprehension when an on-demand dictionary provides word definitions. However useful word definitions may be for vocabulary learning, cognitive load theory warrants concern when embedding dictionaries in narratives because additional processing may reduce the amount of attention available for understanding narrative content. Processing word definitions reduces the available resources in working memory for processing the narrative, thereby raising the risk that children will not understand the story or miss important details. Only when interactive functions highlight the or...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Introduction to international perspectives on digital media and early literacy

- Part 1 Learning and interaction with digital devices

- Part 2 (Early) literacy learning with digital media

- Index