- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

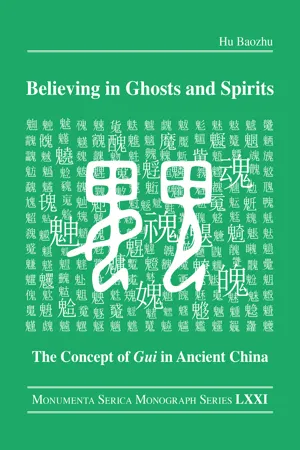

The present book by Hu Baozhu explores the subject of ghosts and spirits and attempts to map the religious landscape of ancient China. The main focus of attention is the character gui ?, an essential key to the understanding of spiritual beings. The author analyses the character gui in various materials – lexicons and dictionaries, excavated manuscripts and inscriptions, and received classical texts. Gui is examined from the perspective of its linguistic root, literary interpretation, ritual practices, sociopolitical implication, and cosmological thinking. In the gradual process of coming to know the otherworld in terms of ghosts and spirits, Chinese people in ancient times attempted to identify and classify these spiritual entities. In their philosophical thinking, they connected the subject of gui with the movement of the universe. Thus the belief in ghosts and spirits in ancient China appeared to be a moral standard for all, not only providing a room for individual religiosity but also implementing the purpose of family-oriented social order, the legitimization of political operations, and the understanding of the way of Heaven and Earth.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1.1 Erya: Gui 鬼 as Gui 歸

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedicated

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface (Roderich Ptak)

- Chronological Table of Chinese History

- Conventions

- Abbreviations

- Keys to the Tables

- A Note on the Translation of the Character Gui

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The Preliminary Understanding of Gui

- Chapter Two: The Original Meaning of the Character Gui: An Examination of Jiaguwen and Jinwen

- Chapter Three: What’s in a Character? Definition and Variegated Characteristics of Gui in the Zuozhuan and Liji

- Chapter Four: Confucian, Daoist, and Mohist Perspectives on the Concept of Gui

- Chapter Five: Folk-oriented Usages of Gui in the Rishu Manuscript

- Conclusion

- Appendix I: Table of the Radical Gui and Its Related Characters

- Appendix II: Gui-related Oracle Bone Inscriptions

- Appendix III: Investigation: Annotated Translation of the “Jie” 詰 Section

- Bibliography

- Index with Glossary