eBook - ePub

Improving Statistical Reasoning

Theoretical Models and Practical Implications

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book focuses on how statistical reasoning works and on training programs that can exploit people's natural cognitive capabilities to improve their statistical reasoning. Training programs that take into account findings from evolutionary psychology and instructional theory are shown to have substantially larger effects that are more stable over time than previous training regimens. The theoretical implications are traced in a neural network model of human performance on statistical reasoning problems. This book apppeals to judgment and decision making researchers and other cognitive scientists, as well as to teachers of statistics and probabilistic reasoning.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Statistical Reasoning: How Good Are We?

SUMMARY: An influential line of research about judgment under uncertainty, the process of making judgments in uncertain conditions, suggests that people cannot avoid making reasoning fallacies. Because it has been claimed that these fallacies might have severe consequences for people in daily life, this research has attracted much attention outside of the field. This chapter reviews the evidence. Research about statistical reasoning commonly starts with a normative model against which people’s answers are evaluated and with a text problem that corresponds to this model. The three models most often used in this research are equations or inequalities that describe conjunctive probabilities, conditional probabilities, and Bayesian inference. A fourth model refers to the impact of sample size. Representative research relating to these four models is described in this chapter. Moreover, common misunderstandings in the interpretation of the results of significance tests, which rely on conditional probability judgments, and whose results are highly sensitive to sample size, are addressed. Although there is an abundance of research demonstrating so-called reasoning fallacies, thorough analysis affords a more complex picture of human reasoning.

Statistical reasoning, sometimes called judgment under uncertainty, has received a great deal of attention in academic circles and in the media since Kahneman and Tversky’s seminal work on the subject in the early 1970s (e.g., Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). What is the reason for this unusually strong interest in psychological research results? Perhaps the interest is because the conclusions drawn have been serious: Human minds “are not built (for whatever reason) to work by the rules of probability” (Gould, 1992, p. 469). Instead, we poor “saps” and “suckers” often “stumble along ill-chosen shortcuts to reach bad conclusions” (McCormick, 1987, p. 24). In more scientific terms, people apply heuristics that lead them to biases or cognitive illusions that might have severe consequences for judgments and decisions (e.g., Arkes & Hammond, 1986; Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982). The problem is viewed as a general one: “Quite without distinction, politicians, generals, surgeons, and economists as much as vendors of salami and ditchdiggers are all, without being aware of it, and even when they are in the best of humors and while exercising their professions, subject to a myriad of such illusions” (Piattelli-Palmarini, 1994, p. x).

How do we know when people’s judgments are indeed in error? In much re-search in this area, there is assumed to be only one correct way to solve a problem, which is derived from logic, probability theory, or statistics (e.g., Kahneman & Tversky, 1982). Usually, researchers have a model in mind according to which they construct a task. This model is normative because it specifies the correct answer. If participants’ answers do not conform to this model, the participants are assumed to have committed reasoning errors. A model can be as simple as the rule that the occurrence of a conjunction of two events is at most as likely as the occurrence of one of the events.

Before this book more closely examines these models and their corresponding tasks, let us return to the sweeping conclusion that we are all poor probabilistscan this be right? This conclusion is certainly wrong in its generality. Christensen-Szalanski and Beach (1984) reviewed a large body of studies about decision making, judgment, and problem solving in the period between 1972 and 1981, in which the performance of participants was compared to some normative model derived from probability theory. They found that about 44% of all studies reported results that reflected positively on human reasoning. These studies, however, were only cited 4.7 times on average in the sampled period, whereas those that put human reasoning in a bad light were cited an average of 27.8 times in the same period. Lopes (1991) attributes this citation bias to the rhetoric associated with the heuristics-and-biases literature and to secondary gains to authors outside psychology (e.g., sociology, political science, law, economics, business, and anthropology) who evoke interest and attention by relating bias problems to substantive issues in their own fields. Indeed, it appears to be more interesting to demonstrate errors than good judgment, which might be obvious or uninteresting. Imagine giving friends or students some tasks to solve and finding that all are able to solve them easily. This result would probably not provoke a lively discussion. However, if people give solutions that they later accept (or do not accept) as wrong, interest in the topic is likely to be high.

Let us assume (until the end of this chapter) that there is only one normative model, meaning rule or principle, for the solution to every task described in the following section, against which people’s solutions can be compared. In this book, we will consider the four models which are probably the most commonly used in the literature about judgment under uncertainty. They specify how conjunctive and conditional probabilities should be treated, how probabilities should be revised given new information (Bayesian inference), and how the size of a sample should influence one’s confidence in the mean or proportion of that sample. This chapter discusses text problems that elicit both poor and good solutions according to each model.1

CONJUNCTIVE PROBABILITIES

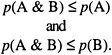

Consider two events: You receive a rise in salary (A) and you fall in love (B). The probability that both events occur, that is, that you receive a rise in salary and fall in love (A & B) in a given period, cannot exceed the probability of either event during the same period. More formally,

|

This model is often referred to as the conjunction rule. Ample research, stimulated by an article by Tversky and Kahneman (1983), has shown that people re-liably often disobey the conjunction rule, a violation typically referred to as the conjunction fallacy. The best known example of a conjunction task is the Linda task (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983). In its simplest form, it reads:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Please indicate which of the two following statements is more likely: Linda is a bank teller.

Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement. (p. 299)

The probability of a conjunctive event (e.g., being a bank teller and in the feminist movement) is commonly judged by a vast majority of participants to be more likely than the probability of a component event (e.g., bank teller), which is a violation of the conjunction rule.

Frequency Format Versus Probability Format

Now let us change the question slightly without changing the description of Linda:

Imagine women who fit the description of Linda.

How many of these women are bank tellers?

How many of these women are bank tellers and active in the feminist movement?

In about 80% to 90% of all cases, participants now adhere to the conjunction rule, as compared to the 10% to 30% usually observed for the first version (Fiedler, 1988; Hertwig, 1995; Tversky & Kahneman, 1983). Even children are able to solve conjunction tasks if the problem information is given in terms of frequencies. Inhelder and Piaget (1959/1964) used pictures showing objects (e.g., yellow primulas and primulas of other colors) that could be brought into inclusion relations (e.g., yellow primulas are included in primulas, which in turn are included in flowers). Most 8-year-olds recognized that conjunctive sets (e.g., flowers that are both yellow and primulas) cannot be more numerous than component sets (e.g., primulas). Why do the results differ when tasks are formulated in terms of frequencies versus probabilities? There are at least two explanations for this effect. One rests on the difference between natural language and the language of probability. For instance, in natural language, many intended meanings are not stated explicitly, but can be easily inferred from the context. In an everyday conversation, and in the context of Linda’s personality description, the statement “Linda is a bank teller” can be understood as “Linda is a bank teller but not a feminist.” This inference may be blocked by a frequency formulation (see chapter 2). The other explanation for this startling effect rests on the observation that over millennia, the human mind was exposed to raw frequencies and not to single-event probabilities. Therefore, evolution tuned cognitive algorithms to frequency formats, wherein numerical information is expressed in terms of frequencies (as in the second version of the Linda task), and not to probability formats, wherein numerical information is expressed in ...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Statistical Reasoning: How Good Are We?

- 2 Are People Condemned to Remain Poor Probabilists?

- 3 Prior Training Studies

- 4 What Makes Statistical Training Effective?

- 5 Conjunctive-Probability Training

- 6 Conditional-Probability Training

- 7 Bayesian-lnference Training I

- 8 Bayesian-lnference Training II

- 9 Sample-Size Training I

- 10 A Flexible Urn Model

- 11 Sample-Size Training II

- 12 Implications of Training Results

- 13 Associationist Models of Statistical Reasoning: Architectures and Constraints

- 14 The PASS Model

- 15 Statistical Reasoning: A New Perspective

- Appendix A Variations of Bayesian Inference

- Appendix B The Law of Large Numbers and Sample-Size Tasks*

- Appendix C Is There a Future for Null-Hypothesis Testing in Psychology?

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Improving Statistical Reasoning by Peter Sedlmeier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.