eBook - ePub

Encyclopedia of AIDS

A Social, Political, Cultural, and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic

- 650 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Encyclopedia of AIDS

A Social, Political, Cultural, and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic

About this book

The Encyclopedia of AIDS covers all major aspects of the first 15 years of the AIDS epidemic, including the breakthroughs in treatment announced at the International AIDS Conference in July 1996. The encyclopedia provides extensive coverage of major topics in eight areas: basic science and epidemiology; transmission and prevention; pathology and treatment; impacted populations; policy and law; politics and activism; culture and society; and the global epidemic. With more than 300 entries written by 175 specialists and illustrated with more than 100 photographs and charts, the Encyclopedia of AIDS is an essential reference work for students at the undergraduate and graduate levels, professionals in a wide variety of medical, service, and care fields, academics, researchers, journalists, and general readers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Encyclopedia of AIDS by Raymond A. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Health Care DeliveryA

Abstinence

Abstinence refers to the practice of refraining from particular behaviors, typically those construed as being negative for or injurious to the person who performs them. In the context of HIV/AIDS, abstinence generally refers to the avoidance of HIV risk behaviors, including injecting drug use or certain sexual activities such as oral sex, vaginal intercourse, and anal intercourse.

In absolute terms, complete abstinence from risk behaviors is the single most effective manner in which to avoid any potential danger of HIV transmission through sex or injecting drug use. This approach to managing risk behavior, referred to as “harm elimination,” is reflected in programs that urge people, particularly adolescents, to “just say no” to all drug use as well as any pre- or extramarital sexual activity.

Harm-elimination approaches to drug use are typically enforced by prohibitionist laws that criminalize not only the use of illegal drugs but also the possession and distribution of needles and syringes. As regards sexual risk behavior, proponents of harm elimination typically endorse abstinence-only educational curricula, resist the distribution of condoms and contraceptives in schools, oppose teaching about homosexuality, and reject sex education in general and safer-sex education in particular. This approach is strongly advocated by religious conservatives, for whom drug use and sex outside heterosexual marriage are viewed not only as public health concerns but also as moral transgressions.

Complete abstinence from risk behaviors may be an attainable goal for some people, but many others may not be able to control their actions while under such powerful influences as sexual attraction and drug dependence or when they are under emotional stress or psychological pressure from others. Further, some who might be capable of controlling their actions may believe that certain risks are inevitable and that quality of life is dramatically compromised by the elimination of all risk. Such individuals may be helped by approaches that emphasize “harm reduction” over harm elimination.

The harm-reduction approach would argue that prevention of the sexual transmission of HIV need not involve abstinence from all sex, but rather only from certain unprotected sexual behaviors. Indeed, this is the fundamental message behind the concept of safer sex. From this perspective, sexual contact of various sorts can be continued as long as potentially infectious bodily fluids are not exchanged. Such a goal could be achieved by abstaining from all penetrative sex while continuing external sexual contact such as mutual masturbation and frottage (non-penetrative rubbing). Another, somewhat riskier alternative to total abstinence is the correct and consistent use of latex condoms during penetrative sex, particularly vaginal and anal intercourse.

In the case of injecting drug use, harm-reduction models usually begin with the reality of a given status quo: that a substantial number of people do, in fact, inject drugs and are likely to continue doing so for the foreseeable future. Although treatment programs designed to end drug dependence are often part of harm-reduction approaches, the greater emphasis is on dealing with the current practices of injecting drug users. The prototypical harm-reduction strategy has been the distribution of clean needles, usually in exchange for used needles. The distribution of bleach kits and information about how to clean used needles would be a distant second choice from the harm-reduction perspective, a strategy to be followed mainly when needle distribution is impossible.

Proponents of abstinence-based programs argue that, in the long run, harm-reduction programs simply serve to deepen fundamental underlying social problems such as drug use and sexual activity outside heterosexual marriage. They argue that making condoms readily available in schools or decriminalizing needle possession is tantamount to legitimating and even condoning such activity. Thus, they contend that non-abstinence-based programs in schools send mixed messages to youth and, in the end, lead more youth to have sex or to experiment with drugs than would be the case with abstinence-only programs. Proponents of abstinence also argue that the distribution of condoms and clean needles in prisons would be a tacit acknowledgment of the prevalence of prohibited activities such as sex and drug use among inmates. Opponents of harm-reduction approaches make pragmatic arguments, such as that many people are unable to control their sexual behavior once in a state of arousal and thus may engage in risky behaviors anyway. They also point out that condoms can and do sometimes rupture, slip off, and leak and thus are not foolproof.

The many ethical and policy debates regarding the question of abstinence have been stormy and sometimes characterized as part of a larger “culture war” being fought between groups with ideologically irreconcilable positions. Advocates of abstinence tend to believe that social leniency engendered the HIV/AIDS epidemic and that it can only be resolved by a return to stricter standards of behavior. Those who view abstinence as only one possible approach of many to HIV prevention tend to focus instead on the rights of individuals to make autonomous decisions.

RAYMOND A.SMITH AND SAMANTHA P.WILLIAMS

Related Entries: Adolescents; Educational Policy; Harm Reduction; Injecting Drug Use; Injecting Drug Users; Interventions; Monogamy; Needle-Exchange Programs; Safer Sex; Safer-Sex Education

Key Words: abstinence, celibacy, harm elimination, harm reduction, monogamy, sex education

Further Reading:

Bullough, V.L., and B.Bullough, eds., Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia, New York: Garland Publishing, 1994

Douglas, P.H., and L.Pinsky, The Essential AIDS Fact Book, New York: Pocket Books, 1996

Kalichman, S.C., Answering Your Questions about AIDS, Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 1996

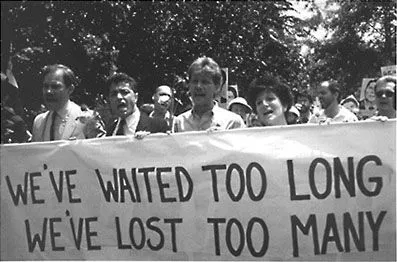

ACT UP

ACT UP, the commonly used acronym for the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, is a grassroots AIDS organization associated with nonviolent civil disobedience. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, ACT UP became the standard-bearer for protest against governmental and societal indifference to the AIDS epidemic. The group is part of a long tradition of grassroots organizations in American politics, especially those of the African American civil rights movement, which were committed to political and social change through the practice of “unconventional politics.”

In its effort to attract media attention through direct action, the African American civil rights movement embraced various elements of unconventional politics, including boycotts, marches, demonstrations, and nonviolent civil disobedience. Like other grassroots organizations, ACT UP has been influenced by the civil rights movement to the extent that it, too, has used boycotts, marches, demonstrations, and nonviolent civil disobedience to attract media coverage of its direct action.

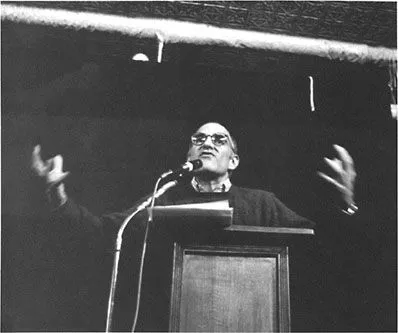

ACT UP was founded in March 1987 by playwright and AIDS activist Larry Kramer. In a speech at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center of New York, Kramer challenged the gay and lesbian movement to organize, mobilize, and demand an effective AIDS policy response. He informed the audience of gay men that two-thirds of them might be dead within five years. To Kramer, the mass media were the central vehicle for conveying the message that the government had hardly begun to address the AIDS crisis. As a part of his speech, he asked this question: “Do we want to start a new organization devoted solely to political action?”

Kramer’s speech inspired another meeting at the New York center several days later, which more than 300 people attended. This event essentially signaled the birth of ACT UP. Thereafter, ACT UP/New York routinely drew more than 800 people to its weekly meetings and thus became the largest and most influential of all the chapters. By early 1988, active chapters had appeared in various cities throughout the country, including Los Angeles, Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco. At the beginning of 1990, ACT UP had spread throughout the United States and around the globe, with more than 100 chapters worldwide.

ACT UP’s original goal was to demand the release of experimental AIDS drugs. In doing so, it identified itself as a diverse, nonpartisan group, united in anger and commitment to direct action to end the AIDS crisis. This central goal is stated at the start of every ACT UP meeting. ACT UP’s commitment to direct activism emerged as a response to the more conservative elements of the mainstream gay and lesbian movement. Underlying ACT UP’s political strategy is a commitment to radical democracy. No one member or group of members had the right to speak for ACT UP; this was a right reserved for all members. There were no elected leaders, no appointed spokespeople, and no formal structure to the organization.

Throughout its existence, ACT UP has made an effort to recruit women and minorities into the organization. Women in ACT UP organized a series of national actions aimed at forcing the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to change its definition of AIDS to include those illnesses contracted by HIV-positive women. ACT UP/New York attempted, without great success, to recruit African Americans and Latinos as part of its organization.

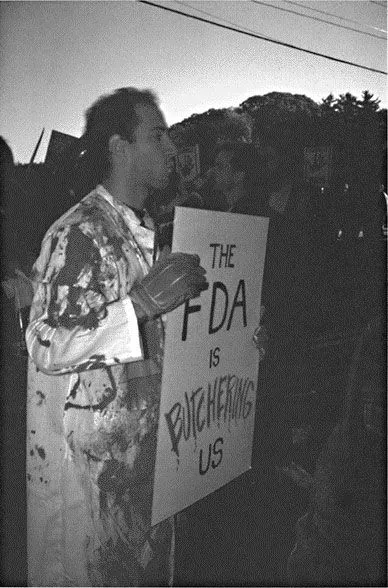

ACT UP members staged their first large-scale demonstration at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) building in 1988. The group was protesting clinical trials of the antiviral drug azidothymidine (AZT) in which some participants were being given placebos rather than the drug itself.

Playwright and AIDS activist Larry Kramer launched ACT UP with an impassioned call to action in March 1987 at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center of New York. This image is taken from the only set of photos taken during Kramer’s speech.

Over the years, ACT UP has broadened its original purpose to embrace a number of specific and practical goals. It has demanded that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) release AIDS drugs in a timely manner by shortening the drug approval process and has insisted that private health insurance as well as Medicaid be forced to pay for experimental drug therapies. Ten years into the AIDS crisis, ACT UP questioned why only one drug, the highly toxic azidothymidine (AZT), had been approved for treatment. The organization demanded answers from policy elites. ACT UP also demanded the creation and implementation of a federal needle-exchange program, called for a federally controlled and funded program of condom distribution at the local level, and asked for a serious sex education program in primary and secondary schools to be created and monitored by the federal Department of Education.

Since its creation in 1987, ACT UP has also publicized the prices charged and profits garnered by pharmaceutical companies for AIDS treatment drugs. The goal was to put considerable pressure on pharmaceutical companies to cut the prices associated with AIDS treatment drugs so that they would be more affordable to people with HIV/AIDS from all class backgrounds. Class and political economy concerns are not central to ACT UP’s ideology, however, but are raised only to the extent that they inform the larger public of the specific ways in which the group believes that pharmaceutical companies pursue profits at the expense of lives.

Thousands of people joined ACT UP chapters in response to what they perceived to be an outrageous lack of governmental support for addressing AIDS. Many were motivated by anger but also shared Kramer’s belief that direct political action on behalf of their lives should be a key element of any organizing strategy. The media were a central target of the group, led by ACT UP members with experience in dealing with the media through professional backgrounds in public relations and reporting.

On June 1, 1987, ACT UP organized a coalition of activists to converge on the White House to demand real action against AIDS. The previous evening, President Ronald Reagan had given his first public address on the six-year-old epidemic, discussing hemophiliacs, blood-transfusion recipients, and spouses of injecting drug users but never once mentioning gay men.

ACT UP embraced slogans such as “Silence=Death” and used political art as a way to convey its message to the larger society. In doing so, ACT UP secured media attention from the start and, as a result, communicated greater awareness of AIDS issues to both the gay and lesbian community and the larger society. The media covered ACT UP’s first demonstration, held on Wall Street in New York on March 24, 1987. The goal of this demonstration was to heighten awareness of the FDA’s inability to overcome its own bureaucracy and release experimental AIDS drugs in a timely fashion. This demonstration became a model for future ACT UP activities. It was carefully orchestrated and choreographed to attract media attention and to convey a practical political message.

Over the years, other ACT UP demonstrations received considerable media coverage. A 1987 protest at New York’s Memorial Sloan-Kettering Hospital called for an increase in the number of anti-HIV drugs. A demonstration targeted Northwest Airlines, also in 1987, for refusing to seat a man with AIDS, and the editorial offices of Cosmopolitan magazine were invaded in 1988 as protesters challenged an article which claimed that almost no women were likely to contract HIV or develop AIDS. In 1988, more than 1,000 ACT UP protesters surrounded the FDA’s Maryland building. In 1989, ACT UP activists demonstrated at the U.S. Civil Rights Commission’s AIDS hearings to protest its ineptitude in responding to AIDS. Also in 1989, ACT UP/New York’s “Stop the Church” demonstration disrupted Roman Catholic John Cardinal O’Connor’s Mass in St. Patrick’s Cathedral to protest his opposition to condom distribution. In one especially memorable action, ACT UP members invaded the studio of the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour on January 22, 1991, chained themselves to Robert Mac-Neil’s desk during a live broadcast, and flashed signs declaring “The AIDS Crisis is Not Over.”

In light of some of these actions, particularly the “Stop the Church” demonstration, ACT UP found itself responding to critics arguing that it had simply gone too far. The confrontational and, many felt, offensive “Stop the Church” demonstration strategy engendered considerable criticism of ACT UP from both within and outside the broader gay and lesbian movement. This and other actions exacerbated an already existing tension within the gay and lesbian movement, between those who favored more traditional lobbying activities and those who embraced the radical direct action associated with ACT UP. Many ACT UP activists became increasingly intolerant of those who worried that direct action alienated important policy elites. In addition, ACT UP came under renewed criticism from within for the chaotic, unwieldy, and often unfocused nature of its weekly meetings.

By 1992, there were also divisions within ACT UP over what should be appropriate political strategy. Since ACT UP’s creation in 1987, AIDS activists had directed their anger toward perceived enemies, including the U.S. Congress and president, federal agencies, drug companies, the media, religious organizations, and homophobic politicians in positions of power at all levels of society. The divisions within ACT UP undermined organizational and movement solidarity. These divisions helped spawn other organizations, whose membership was largely composed of individuals who had previous connections to ACT UP. Queer Nation, a short-lived, radical gay and lesbian organization, appeared in June 1991 with a goal of radicalizing the broader AIDS movement by reclaiming the word “queer” and embracing confrontational politics.

In 1992, those ACT UP activists committed to a political strategy emphasizing the treatment of individuals with HIV/AIDS left ACT UP/New York and formed the Treatment Action Group (TAG). Unlike ACT UP, which was characterized by a democratic organizational structure, TAG accepted members by invitation only, and membership could be revoked by the board. In addition, TAG members received salaries, and the group accepted a $1 million check from the pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome, the manufacturer of AZT, on behalf of TAG in the summer of 1992. TAG used this money to finance member travels to AIDS conferences throughout the world, to pay members’ salaries, to hire professional lobbyists, and to lobby government officials.

TAG’s central goal has been to force the government to release promising AIDS drugs more quickly and to identify possible treatments for opportunistic infections....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- A Caution to Readers

- Foreword

- Foreword

- Editor’s Note and Guide to Usage

- Editors and Contributors

- Alphabetical List of Entries

- Resource Guide

- The Aids Epidemic: An Overview (with thematic listings of encyclopedia entries)

- Encyclopedia Entries

- List of Commonly Used Terms and Abbreviations

- Notes on Editors and Contributors

- Index

- Photographic Acknowledgments