![]()

Part I

EARLY LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

![]()

Chapter 1

The Role of Modality and Input in the Earliest Stage of Language Acquisition: Studies of Japanese Sign Language

Nobuo Masataka

Kyoto University

There is no single route to the acquisition of language, and children, particularly in early childhood, show a large range of individual variation both in their speed of development and in the strategies they employ. Their progress through early language might be thought of as a journey through an epigenetic landscape rather than a passage through a linear succession of stages. This notion is most convincingly demonstrated along studies that compared the language development of deaf children with that of hearing children. Recent studies of signed language development in children growing up in a signing environment from birth reported that the language is acquired by much the same route as spoken language (Caselli, 1983, 1987; Volterra, 1981; Volterra & Caselli, 1985). First signs appear at a similar time to first words. When deaf children first use signs, they do so to refer to objects, individuals, and events with which they become familiar within the social-interactional context, just as hearing children initially use words. The learning of early sign combinations is also comparable to the learning of early word combinations as is the mastery of syntax.

However, as to how this is accomplished, little is known yet, and this is particularly the case during early infancy. Thus, I devote this chapter to consider the role of both modality (speech vs. sign) and input (deaf vs. hearing) in the earliest stage of language acquisition. This chapter actually consists of two major sections, motherese and babbling. First, the perception of linguistic input typically characteristic during early infancy is compared between deaf and hearing infants, and then the effects of the presence or absence of such input are examined.

PREVIOUS FINDINGS ABOUT MOTHERESE

It is a commonplace observation that adults tend to modify their speech in an unusual and characteristic fashion when they address infants and young children. Charles Ferguson (1964) first offered a coherent description of the linguistic features of this modified speech known as motherese. Since that study, our knowledge about paralinguistic or prosodic features of parental speech to infants has been accumulating (Garnica, 1977; Newport, Gleitman, & Gleitman, 1977; Papousek, Papousek, & Bornstein, 1985). The linguistic modifications of motherese include fewer words per utterance, more repetitions and expansion, better articulation, and decreased structural complexity (Ratner & Pye, 1984; Snow, 1977). Prosodic features include higher overall pitch, wider pitch excursions, more distinctive pitch contours, slower tempo, longer pauses, and increased emphatic stress (Garnica, 1977; Masataka, 1992a). Gross-linguistic research has documented common patterns of such exaggerated features in parental speech to infants younger than 8 months of age across a number of European languages and Japanese (Fernald et al., 1989; Masataka, 1992b) and in maternal speech in Mandarin Chinese (Grieser & Kuhl, 1988). The various earlier studies suggest that motherese may have universal linguistic and prosodic features.

Interest in the structure and function of motherese stems from the possibility that such speech may enhance the young child’s language learning. Indeed, several experimental studies investigated the salience of motherese for young children and, up to now, the features were assumed to serve three functions, all of which are related to spoken language development. First, the enhanced acoustic features of motherese may differentially elicit and, perhaps, maintain the infant’s attention. Three- to 4-month-old infants are more likely to pay attention to motherese than adult-directed speech. Fernald (1985) demonstrated that infants turned their heads more frequently in the direction necessary to activate a recording of female infant-directed speech than female adult-directed speech, using a conditioned head-turning procedure. A more recent study by Cooper and Aslin (1990) showed that infants’ preference for exaggerated prosodic features was present when tested at the age of 2 days. Second, a possible affective role of motherese has been reported. The linguistic relevance of affect in spoken language acquisition is demonstrated by findings that 4- to 9-month-old infants are responsive to meaning conveyed by prosodic contours long before they respond to the segmental content of utterances by adults (Papousek et al., 1985; Sullivan & Horowitz, 1983). The infants’ direct and affective responding to the prosodic features of the vocalizations around this age does not require linguistic comprehension because the phonetic form becomes gradually decontextualized from its typical prosodic pattern at a later point of development. Rather, the earliest signs of comprehension of speech are mainly mediated by affect. This interpretation is supported by the finding that 4- to 5-month-old and 7-to 9-month-old infants who watched videotapes of a woman talking to an infant or talking to an adult demonstrated more positive affect while watching the infant-directed tape (Werker & McLeod, 1989). Furthermore, the magnitude of this effect was greater in the case of younger infants. These results indicate that infants find infant-directed speech less affectively ambiguous than adult-directed speech. They appear to show more readiness for social engagement when listening to motherese than when listening to adult-directed speech, and this tendency is more robust in younger infants. Finally, a potential linguistic benefit of motherese may exist. Motherese facilitates the infant’s detection and discrimination of major linguistic boundaries. Certain characteristics of motherese make these boundaries more noticeable, thereby “instructing” infants about language (Karzon, 1985). No doubt, not all of these three functions are necessarily active at the same time. The particular function such input serves could change with the developmental status of the infant and, probably, the attention-getting properties and the affective roles of motherese are mainly called for before the infant is old enough to process the syntactic form of the speech directed toward him or her.

Taken together, the available data indicate that motherese is a prevalent form of language input to infants, at least in speech, and that the salience of motherese for the preverbal infant results both from the infant’s attentional responsiveness to certain sounds more readily than others and from the infant’s affective responsiveness to certain attributes of the auditory signal. In this chapter, I describe the results of a series of experiments in which I have attempted to identify these characteristics of motherese in mother-infant communication in Japanese Sign Language (JSL). The results reveal that a phenomenon quite analogous to motherese in maternal speech is present in the signing behavior of deaf mothers when communicating with their deaf infants. Although humans apparently possess some innately specified capacity for language (e.g., Chomsky, 1975), flexibility exists with respect to the modality in which the capacity is realized in each individual. This leads to the possibility that the specifically patterned linguistic input that is expressed as motherese might enhance infants’ acquisition of the basic forms of the language equally in either the signed or spoken modalities. This is indeed the case as revealed by the studies I describe.

SIGN CHARACTERISTICS OF DEAF MOTHERS INTERACTING WITH THEIR DEAF INFANTS

An important characteristic of motherese is that mothers substantially alter the acoustic characteristics of their speech when they address their infants. Therefore, as a first step in my studies of the sign motherese phenomenon, I examined the possibility that a similar phenomenon might occur in a signed language by comparing the movements associated with each sign when deaf mothers were interacting with their deaf infants and when they were interacting with their adult deaf friends.

Preliminary evidence suggesting the existence of motherese in signed languages was previously found by Erting, Prezioso, and O’Grady-Hynes (1990). They focused on the sign for MOTHER produced by two deaf mothers, who had acquired American Sign Language (ASL) as their first language, during interaction with their deaf infants when the infants were between 5 and 23 weeks of age as well as during interaction with their adult friends. When a total of 27 MOTHER signs directed to the infants were compared with the same number of the signs directed to the adults, the mothers were found to (a) place the sign closer to the infant, perhaps the optimal signing distance for visual processing, and (b) orient the hand so that the full handshape was visible to the infant. Moreover, (c) the mother’s face was fully visible to the infant, (d) eye gaze was directed at the infants, and (e) the sign was lengthened by repeating the same movement. These results appear to support the claim that parents use special articulatory features when communicating with infants, including parents from a visual culture whose primary means of communication is visual-gestural rather than auditory-vocal.

In a series of experiments investigating sign motherese, I attempted to replicate the finding with a larger sample of participants who live in a different cultural background from those studied by Erting et al. (1990) with a more extensive methodology for analysis of signs. The mothers I studied had all acquired JSL as a first language. In all, 14 mothers participated in the recordings. Eight of them were observed when freely interacting with their deaf infants and when interacting with their deaf adult friends (Masataka, 1992a). The remaining 5 were instructed to recite seven prepared sentences either toward their infants or toward their adult friends (Masataka, 1996). Recordings were made with each mother and her infant or friend seated in a chair in a face-to-face position. The height of each chair was adjusted such that eyes of the mother, her infant, and her friends were about 95 cm above the floor. The infant’s body was fastened to the seat by a seat belt. The mother’s behavior was monitored with two video cameras. One of the two provided the frontal view and the other captured the profile. At the beginning of each recording session, the mother was instructed to interact with her infant or friend as she normally might when they were alone together. She was also told not to move her head during the session. Nearly all signed languages studied to date, including ASL, are known to use head movement as well as facial expression for linguistic as well as affective purposes. However the role of such cues from a grammatical perspective is not fully understood in JSL at this time.

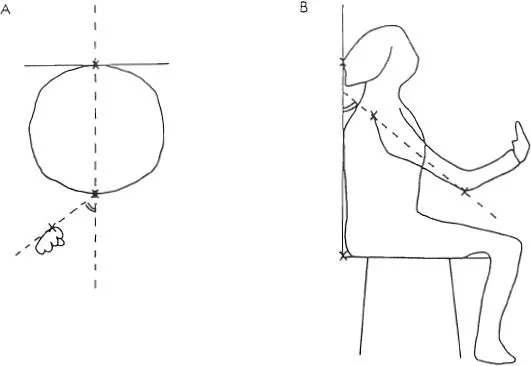

For each recognizable sign recorded on the tape, the following four measurements were performed: (a) duration (number of frames), (b) average angle subtended by the right hand with respect to the sagittal plane of the mother, (c) average angle subtended by the right elbow with respect to the body axis of the mother, and (d) whether the mother repeated the same sign consecutively or not. For measuring the positions of the hand and the elbow, each of the frames was projected by a movie projector onto a digitizer, which was connected to a minicomputer. By plotting the position of the hand and the head or the position of the elbow and the body axis on the digitizer with a light pen, the computer measured the angle between them with an accuracy of 0.5° (see Fig. 1.1). Subsequently, measured values were averaged for each sign by the mother. These measurements were calculated to analyze the degree of exaggeration of signing by the mother. Whereas spoken languages are processed by hearing infants mainly by the auditory mode, signed languages are processed by deaf infants in the visual mode. Thus, it was hypothesized that the degree of exaggeration of signing should be elucidated by measuring the position of the hand and the elbow; that is, when exaggeration occurred in making the signing gestures, it was expected to become most robust in the pattern of movements of hands and arms.

FIG. 1.1. Schematic representation of the plane view (A) and the side view (B) of the mothers as recorded on film. The points marked by a light pen on the digitizer are indicated by an X (from Masataka, 1992a).

As shown by Table 1.1, striking differences were found with regard to all four of the parameters measured. All the differences were statistically significant. For analysis of the duration of signs, values were averaged across participants for each condition. The duration was longer in the case of signs directed to infants than in the case of signs directed to adult friends. When the angle of the hand and elbow subtended to the sagittal plane or body axis was calculated across participants for each condition, the same tendency was apparent. Mean scores for maximum values of angles for each sign directed to infants significantly exceeded those for signs directed to adults with respect to both the hand and the elbow. Similarly, mean scores of averaged values of angles for each sign directed to infants significantly exceeded those for signs directed to adults. With regard to all three of these parameters, post hoc comparisons revealed that each participant demonstrated a significant increase in these scores when she interacted with her infant. Comparison of the rates of repetition for infant-directed and adult-directed signs also indicated that the mean repetition rate for the 13 mothers was greater when they interacted with their infants than when they interacted with their adult friends, and that each individual mother demonstrated a significant increase in repetitions when she interacted with her infan...