eBook - ePub

Monitoring Bathing Waters

A Practical Guide to the Design and Implementation of Assessments and Monitoring Programmes

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Monitoring Bathing Waters

A Practical Guide to the Design and Implementation of Assessments and Monitoring Programmes

About this book

This book, which has been prepared by an international group of experts, provides comprehensive guidance for the design, planning and implementation of assessments and monitoring programmes for water bodies used for recreation. It addresses the wide range of hazards which may be encountered and emphasizes the importance of linking monitoring progra

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Monitoring Bathing Waters by Jamie Bartram,Gareth Rees in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architettura & Metodi e materiali in architettura. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1*

INTRODUCTION

From 1993 to 1998 the World Health Organization (WHO) worked on the progressive development of its Guidelines for Safe Recreational-Water Environments (WHO, 1998). The Guidelines comprise a health risk assessment of recreational water use to be published in two volumes (Volume 1: Coastal and Fresh-Waters and Volume 2: Swimming Pools, Spas and Similar Recreational-Water Environments). This present book is designed to complement the Guidelines for Safe Recreational-Water Environments, providing a practitioners’ guide to the monitoring and assessment of coastal and freshwater recreational environments. It presents, in a methodological format, the information necessary to design and implement a monitoring and assessment programme for recreational water environments.

Surface and coastal waters are used for a variety of leisure and recreational activities, and for other purposes including transport, food production, hydroelectricity generation, as a transport medium and as a repository for sewage and industrial waste. Such activities are not always compatible with one another. Water and its recreational use have long been recognised as major influences on health and well being. The health benefits of bathing in saltwater were, and still are, promoted with enthusiasm. Sea water was once considered as an alternative medicinal treatment to spa water. Water-based recreation is an important component of leisure activities and tourism throughout the world. Tourists are responsible for the significant movement of economic resources both within and between countries. This may be typified by the annual influx of tourists from northern European countries to the countries surrounding the Mediterranean. A similar effect may occur within some countries where certain regions are favoured holiday destinations by those from other regions within the country.

Recreational use of the water environment may offer a significant financial benefit to the associated communities but it also has implications for health and for the environment. Visitors exert a variety of pressures on the very environment that attracts them. Water-based recreation and tourism can also expose individuals to a variety of health hazards, ranging from exposure to potentially contaminated foodstuffs and potable water supplies, through to exposure to sunshine and ultra violet (UV) light and to bathing in polluted waters. Water, however clean, is an alien environment to humans and thus it can pose hazards to human health even when it is of pristine quality.

The varied nature of the hazards to human health and well-being posed by recreational waters demands a full audit of the relative importance of the resultant health effects and the resources required to mitigate those effects. Undoubtedly, the public health outcomes of accidents (including drowning and trauma associated predominantly with diving incidents) and potential infections acquired from contaminated waters are those that demand most attention world-wide.

All the trends indicate that leisure activities, including water-based recreation, will continue to increase. Thus the effects of the health hazards that face recreational water users are likely to gain more prominence in the future. Those responsible for monitoring the likely health impacts of recreational water use are going to face increasingly complex challenges as recreational uses diversify and the number of users increases.

1.1 Health hazards in recreational water environments

Amongst the unequivocal adverse health outcomes resulting from recreational water exposure are drowning and near-drowning. Such injuries account for a significant annual death toll, often associated with reckless behaviour and/or alcohol consumption. Unsafe diving into water bodies can lead to a range of traumatic injuries, including spinal injury, which ultimately may result in quadriplegia. More common, but less severe, incidents include those arising from discarded materials, such as glass, cans and needles on beaches and on the bottom of the bathing zone. Of particular concern is the presence of medical waste, particularly hypodermic needles. Chapter 7 addresses the dangers due to accidents and injuries including those associated with drowning and spinal injury.

The pathogenic micro-organisms that can be found in water bodies have a wide range of sources. These include sewage pollution, organisms naturally found in the water environment, agriculture and animal husbandry and the recreational users themselves. Sewage of domestic origin comprises a particularly unhealthy mixture of micro-organisms. The microbiological hazards encountered in water-based recreation include viral, bacterial and protozoan pathogens. Primary concern has usually been directed towards gastro-intestinal illnesses acquired from recreational waters, although acute febrile respiratory illness and infections of the eye, ear, nose and throat have all been identified as acquired through bathing. The link between recreational water use and more serious infections such as meningitis, hepatitis A, typhoid fever and poliomyelitis is difficult to determine unequivocally.

A key environmental effect of sewage discharges is nutrient enrichment largely, but not exclusively, attributable to phosphate and nitrate in the sewage. This nutrient enrichment can lead to localised eutrophication, which in turn is associated with more frequent or severe algal blooms. Prolonged and excessive eutrophication has also been responsible for algal blooms on a regional basis, such as those in the Adriatic and Baltic Seas in recent years.

A review of human health effects arising from exposure to toxic cyanobacteria, as well as discussion of the detailed analysis of toxic cyanobacteria in water and of their monitoring and management, is available in a companion volume in this series, Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water (Chorus and Bartram, 1999). Chapter 10 in this book deals with the monitoring and assessment of toxic cyanobacteria and algae in recreational waters and also provides a framework for assessing under what circumstances such organisms may pose a priority hazard.

A number of other health hazards may be encountered during recreational water use but which are typically local or regional in distribution. These include: chemical contaminants, arising principally from direct waste or wastewater discharge; non-venomous disease-transmitting organisms (e.g. mosquitoes as malaria and arboviral disease vectors and freshwater snails as intermediate hosts of the schistosomes that cause bilharzia or schistosomiasis); hazardous animals encountered near water (such as crocodiles and seals) and venomous invertebrates (such as sponges, corals, jellyfish, bristleworms, sea urchins and sea stars); and venomous vertebrates (catfish, stingrays, scorpionfish, weaverfish, etc.). The health risks associated with these hazards are outlined in the WHO Guidelines for Safe Recreational-Water Environments (WHO, 1998). Approaches to monitoring and management of these health hazards are often strongly influenced by local factors and for this reason the issue is dealt with here in generic terms, allowing the reader to make informed responses to circumstances where such hazards may arise (Chapter 11).

Excessive exposure to UV, although not exclusive to water-based recreation, may pose a significant health risk if recreational water users do not take appropriate care. Acute effects, such as the discomfort and injury associated with sunburn, or delayed effects (which may include malignant melanoma) are direct adverse health outcomes. Cold water is an important contributory factor in many cases of drowning, and excessive exposure to heat and/or cold can also be associated with adverse health outcomes. These issues are fully addressed in the WHO Guidelines for Safe Recreational- Water Environments (WHO, 1998). Hazards attributable to physical components, such as exposure to extremes of temperature or to excess UV radiation, are not included in this book due to the limited contribution that monitoring and assessment can make to risk management in this context.

1.2 Factors affecting recreational water quality

The health risks posed by poor quality recreational waters generally relate to infections acquired whilst bathing. A range of pollutants enters recreational waters from a number of sources—coastal waters can be regarded as the ultimate sink for the by-products of human activities. In terms of the quality of coastal recreational waters and the resultant impact on human health, the key sources of pollutants are riverine inputs of domestic, agricultural and industrial effluents and direct sewage discharges from the local population. Apart from regular discharges through short and long sea outfalls, irregular discharges may occur through storm water and overflow outfalls, and through unregulated private discharges. Freshwater bathing sites are subject to the same polluting sources as coastal sites, although the scale and extent of these sources may be easier to predict in more clearly delimited freshwater sites.

In both coastal and freshwaters the point sources of pollution that cause most health concern are those due to domestic sewage discharges. Diffuse outputs and catchment aggregates of such pollution sources are more difficult to predict. Discharge of sewage to coastal and riverine waters exerts a variable polluting effect that is dependent on the quantity and composition of the effluent and on the capacity of the receiving waters to accept that effluent. Thus enclosed, low volume, slowly-flushed water systems will be affected by sewage discharges more readily than will water bodies that are subject to rapid change and recharge.

Water-based recreation and leisure activities contribute relatively little to pollution inputs and associated adverse health outcomes when compared with other sources of aquatic pollution, such as sewage outfalls. Pollution originating from water-based recreation and leisure craft includes sanitation discharges, fuel spillages, the environmentally toxic effects of antifouling compounds and general debris. Because water-based recreational activities often occur in estuaries or embayments, any polluting effects may be exaggerated due to the enclosed nature of the system and the subsequent accumulation of pollutants. This is particularly evident in the large number of boating marinas that have been developed over recent years, where there is often a high density of craft and the associated crew, adjacent to bathing waters. Appropriate controls on sanitation discharges from pleasure craft are dependent on suitable holding tanks and port reception facilities. The contribution that such vessels make to the total sewage inputs may be small, but may become more significant in the situations described above where vessels aggregate.

Environmental hazards attributable to pleasure craft may also arise from fuel spillages or discharges. Oil, petrol and diesel may be spilt at filling barges and bilge waters may be discharged, adding to pollution of the coastal environment. Two-stroke outboard engines are thought to exert an annual polluting effect several times greater than that attributable to high profile oil-tanker disasters such as that of the Exxon Valdez (Feder and Blanchard, 1998). Apart from the fuels themselves, the emissions from the engines may be harmful and the oil and petrol mix in two-stroke fuels has been implicated in the tainting of fish and shellfish products. This type of pollution, therefore, can pose an indirect threat to health.

The toxic nature of antifouling paints applied to prevent the attachment and subsequent growth of organisms on pleasure craft hulls and on coastal installations defines them as environmental pollutants. They may thus have an effect on water quality, particularly where vessels are concentrated or the area is enclosed. Such effects are usually considered to affect the marine biota rather than human health.

Pleasure craft and their users undoubtedly contribute significantly to the load of marine debris. Plastics, fishing gear, packaging, food and other wastes are discarded overboard, even when there are controls to prevent this. About 70–80 per cent of marine debris comes from land-based sources and the rest comes from vessels and installations. Such materials rarely affect water quality and human health but do have environmental effects and contribute enormously to aesthetic pollution.

1.3 Effective monitoring for management

Particular types of recreational activities may be associated with certain hazards and therefore discrete patterns of action may be taken to reduce the risk of these hazards. For example, untreated sewage discharges will pose one type of risk—that of infection to bathers; glass discarded on a beach will pose a different type of hazard—injury to walkers with bare feet. Effective sewage discharge procedures can address the former and regular cleaning of the beach coupled with provision of litter bins and educational awareness campaigns can reduce the latter hazard. Therefore, each type of recreational activity should be subject to assessment to determine the most effective control measures. This assessment should include factors that may have a moderating effect on the particular type of risk, such as local features, seasonal effects and the competence of the participants in the activity where the risk is encountered.

The importance of effective use of information from monitoring must be stressed. There is little point in generating monitoring data unless they are to be used. The eventual use of the information products resulting from monitoring should guide and determine all the stages of the monitoring process from the setting of objectives through to design and implementation, reporting and to co-ordination of follow-up. The principal components of management of recreational water use areas for the protection of public health are described in Chapter 5.

For any monitoring and assessment programme to be effective there must be clear management outcomes from the use of the data produced. Effective monitoring requires collection of adequate quantities of data of the appropriate quality, and an understanding of the link between monitoring and management (and therefore to whom, in what format and when information would be best provided). Subsequent actions may be remedial, may provide public information or may inform planning. For example, microbiological monitoring data can be used to justify improved treatment of coastal sewage discharges or, alternatively, to indicate that a small investment in injury and prevention measures will yield more substantial public health benefit. The information links between regulators, government and industry, and those that can provide the financial support for remedial initiatives, must be based on good quality data.

In order for individuals to be able to make knowledgeable decisions about their ultimate recreational destinations, based on the existing facilities and the environmental quality of the available options, they must be aware and informed. Ideally, such judgements should be based on good quality, readily understandable and easily accessible information. Individual choice of site of recreational activity may indirectly result in improved levels of recreational water and bathing beach management by local and national governments. Furthermore, individuals can take responsibility for some important actions to protect their own health and well-being whilst involved in water-based recreation.

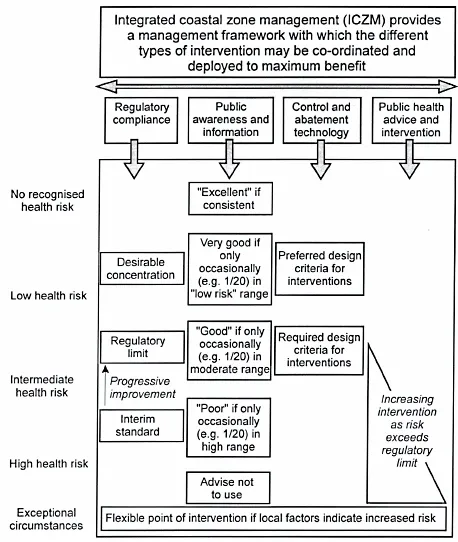

The WHO Guidelines for Safe Recreational-Water Environments (WHO, 1998) describe management actions that support improved safety in recreational water use in four broad areas under the umbrella of integrated coastal or basin management (Figure 1.1). All four broad areas rely on the output of sound monitoring and assessment processes for effective implementation. Several activity levels can be defined at international, national, regional and local levels. Actions that may be taken at international and national level consist primarily of the setting of standards, and such actions are the province of government. There are many local actions that can be undertaken and which may have a significant impact on the well-being of recreational water users. These include basic beach management schemes, comprising lifeguard provision, appropriate sanitation facilities, potable water, parking, medical facilities, beach cleaning, emergency communication and zoning of activities to avoid conflict. These initiatives are largely the domain of local municipalities or of the owners of private beaches. Although all these management measures have attributable direct costs, they may have major indirect benefits in the form of increased recreation and leisure at the location. Beach award schemes (see Chapter 6) harness the willingness of municipalities to provide such facilities.

Figure 1.1 Management framework and types of intervention in relation to different types and degrees of hazard associated with recreational water use

Effective monitoring also requires the participation of all authorities, organisations, industries etc. with a vested interest. This implies that an agency involved in monitoring should ensure and maintain effective channels of communication with non-governmental organisations, industry (especially tourism), local and central government, trade associations, resort and tourism operators and elements of the media. Often monitoring and regulatory agencies are concerned with the quality and veracity of data, but are less aware of the need to package the information and display the results in ways that are easily understood by participating partners, i.e. the same partners with which they are trying to maintain links.

Many uses of the water environment have the capacity to conflict with each other. Such competing pressures must be monitored in a coherent fashion to minimise conflict and, where appropriate, risk to health. Conflict may arise between different groups of water users or between local users and those visiting an area. It is one of the primary roles of effective management to accommodate competing, and often conflicting, uses. When tourism and leisure-based activities are major revenue sources in a region, it is important to strike the correct balance between the demands of water-based recreation and the needs of the environment. Different recreational activities can also interact in a counter-productive fashion—angling, boating, surfing, bathing and waterskiing cannot all take place on the same area of water at the same time without some form of regulation. It is essential that effective planning and consultation processes exist to ensure that appropriate management practices are implemented and monitored. Such planning may enable what is generally a limited resource to be channelled into the most appropriate activities at a particular location. Visitor pressure can be managed more effectively by such means and the health and well-being of the individual and the environment is usually best served in this way.

1.4 Good practice in monitoring

The chapters of this book each include an element of good practice in the monitoring and assessment of recreational waters. Together these elements constitute a Code of...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Design of Monitoring Programmes

- Chapter 3: Resourcing and Implementation

- Chapter 4: Quality Assurance

- Chapter 5: Management Frameworks

- Chapter 6: Public Participation and Communication

- Chapter 7: Physical Hazards, Drowning and Injuries

- Chapter 8: Sanitary Inspection and Microbiological Water Quality

- Chapter 9: Approaches to Microbiological Monitoring

- Chapter 10: Cyanobacteria and Algae

- Chapter 11: Other Biological, Physical and Chemical Hazards

- Chapter 12: Aesthetic Aspects

- Chapter 13: Epidemiology