![]()

Part 1

Insights from Black theology for group exercises and Bible study

![]()

1

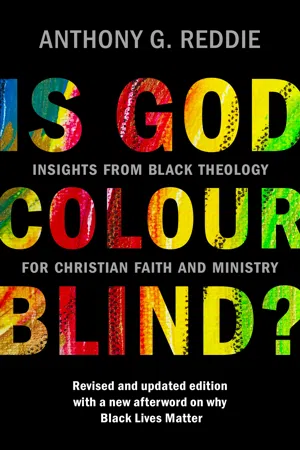

Affirming difference: avoiding colour-blindness

This chapter offers a creative and participative approach to addressing issues of racial justice within the context of adult Christian education and theological education. In the past twenty years that I have worked as a theological educator, I have developed a range of theological resources for addressing various issues in pastoral ministry and Christian discipleship. Since the mid 1990s, I have become a source of specialist theological knowledge and insight, for example in the areas of racial justice, consciousness-raising and Black empowerment, by means of Black theology and Christian education.

One of my primary aims has been to assist in raising the consciousness/awareness and commitment of ministers and lay people to justice issues, and the creation and development of the following exercise has been influenced by such concerns. However, it should not be construed as being a specific or dedicated racial-justice training initiative per se. Rather, this exercise is essentially a contextual and applied theological approach to transforming individuals and churches, and our assumptions about the nature and role of the Christian faith in predominantly Western technological, liberal democratic nations. I am interested in creating learning opportunities for lay and ordained people (principally those who have leadership responsibilities), in order that they may affirm and empower others in the Christian faith.

An exercise in affirming difference

This exercise has been developed to help participants realize that difference is positive and that we do not all need to be subsumed into one (White) culture. Do not let on to participants that this is the purpose of the exercise until the end of the exercise!

The meal test

Ask each person to imagine the following scenario:

•You are a member of a club or organization. That club expresses its identity and togetherness by means of a weekly formal meal. The meal is held on a specific day and time in the week, every week.

•Every member of the club is invited to the meal and has a major decision to make when they arrive at the entrance of the room where the meal is being held. You can now choose between two meals, and as a member there is no difference in cost, and everyone eats together:

1On the one hand, you can choose the ‘set meal’. This is the standard accepted meal. It has already been prepared and is already on the menu.

2Alternatively, you can eat your favourite meal. This has been prepared for you in exactly the way you want and has been cooked to perfection.

•Which meal do you choose? The one everyone else might be eating or your own special meal? You have absolute choice, and as a full member of the club, you are there at the meal on the same terms as everyone else. Which meal?

Instructions for the facilitators

•The group are never told what the standard meal is, but do tell them that:

1At any given time most of the members of the club will be eating the standard meal as many do not have a favourite or could not be bothered to choose it.

2The meal is thought to be perfectly acceptable to and adequate for most of the existing members.

•The facilitator should stand in front of each individual as they are asked the question and repeat the following phrase: ‘Are you really sure you want to choose that meal?’ (whether it is their favourite or the standard). The purpose of doing this is to put doubt into the mind of each individual. Part of the aim of the facilitator is to get them to change their mind.

•When you have asked the question a number of times, go back through the conversations. Who chose what? Who changed their minds? How many stuck with their favourite meal?

•Why did certain individuals change their minds? What was the relationship between the standard and the favourite meal?

•Does everyone need to eat the same meal in order for the club to be united? What happens if everyone decides to eat their favourite meal?

Reflecting on the exercise

The above exercise has been used on numerous occasions in formal educational settings (theological/seminary students training for ordained ministry) or informal ones (lay people in adult education groups in local churches). On those occasions when I have used it a number of salient features have emerged from the resultant reflections.

We choose certain meals because they suit us, we like them, they meet our needs. Those meals say something about our culture and personality. They speak of an emotional response, a sense of identity. We all want to be fed in a manner that meets our needs. For those who chose their favourite meal, it in no way represents a disparaging of the other meal. Simply, it is an expression of one’s preference, for that which is authentic and preferable to that individual.

This exercise serves as a metaphorical way of entering into the dynamics of ‘race’, power and difference, which have always be-devilled Christian communities and the Church as a whole. Often, in order to deal with the fractures of ‘race’, ethnicity, gender and sexuality (as we shall see them arise in the exercises in the later chapters of this book), Christian theology has sought to spiritualize the central heart of the gospel. This spiritualization has been effected in order to overcome notions of physical or embodied difference, which often asserted a form of White, Euro-American normality in the propagation and interpretation of the gospel.

This can be seen in the way in which the standard meal is surreptitiously (or not so subtly depending upon how the exercise has been enacted) used as the norm by which the various favourite meals are defined. The favourite is invariably challenged and undermined by the facilitator.

In the exercise, food is the metaphor for culture and humanity. Too often, the wider societies in many predominantly White Western countries have neither reflected nor met the cultural and emotional world of Black people. While some have utilized Black cultural practices, such as tapping into their music, popular culture, fashion, art, expression and so on (often for commercial gain), they have not affirmed the peoples themselves.2

Some people may have chosen to eat the standard meal. If that was their choice and they genuinely do not mind not giving up their favourite and would really prefer to eat the standard meal, then that is fine. But there are many Black people who would genuinely prefer to eat their favourite meal but cannot bring themselves to admit this in public for fear of being identified as being ‘separatist’ or accused of not wanting to ‘integrate’.

Often, in White majority Christian-influenced societies, the emphasis is upon ‘integration’ and a ‘colour-blind’ doctrine as a means of handling contentious issues of difference. In the context of the meal-test exercise this involves Black people being persuaded to eat the standard meal; that is, to be less like themselves and to be the same as that which is characterized as the standard or the norm, namely White people. This move is often demanded of them in order that we may all be one. In effect, for the body of Christ to function as one unified entity it is necessary that the ‘meal’ become one where differences are sublimated and, rather, a homogeneous ‘standard’ is effected, where alternative meals (represented difference in terms of ‘race’ and ethnicity are ignored) are coercively outlawed by pressure from those with power (the seemingly genial host). When I have been the facilitator I have often played the genial host mirroring the often surreptitious way racism operates in the UKi – often through an implicit conflation of alleged ‘high culture’, cultural norms and traditions (‘We’ve always done it like this’) and a seemingly polite but nevertheless insistent imposition that one ‘becomes more like us’ in order to belong.

Marginalized and oppressed people get it every time

Perhaps the most striking point to make is the fact that those who are marginalized or oppressed within many Western societies, whether on grounds of ‘race’ (the central point of departure in this study), gender, class, sexuality or disability, have immediately caught sight of the underlying truth of the metaphor. The meal test is not about a meal. It has been interesting to witness the number of predominantly White, middle-class, articulate males (particularly clergy) who have been, as we say in Britain, ‘a little slow on the uptake’, meaning they have not caught on very quickly.

If those who are representative of powerful, privileged and advantaged backgrounds do not ‘catch on’ very quickly, then why should that be the case?

The answer I believe lies in the experiential subjectivity of those on the margins. It is my contention that those who are marginalized have, through their enforced position and experience, learnt how to operate within a double-consciousness framework. This is one where the repressed and marginalized subject is able to ‘read’ the values of the dominant world while juxtaposing this often enforced reality alongside their innate subjectivity. Charles Foster and Fred Smith see notions of double consciousness as an essential paradigm and narrative thread in the work of Grant Shockley, one of the pioneers of a liberative approach to Christian education in the African American experience.3

The failure of often White middle-class professionals to see what was happening in the exercise has for me, as the facilitator and educator, been an interesting point of analysis. In the first instance, this form of reversal of the normal locus or location of authority within the dynamic of community formation is reflective of some of my previous work in the area of pedagogy in Christian learning contexts.4 In fact I would assert that one of the most powerful and important ‘learning outcomes’ of this exercise has been the extent to which those with power who normally predominate in the usual dynamics that govern community formation are often the ones who feel disadvantaged in this seemingly innocent experiential exercise. As I will demonstrate when reflecting on the important transformative truths to be discerned from this exercise, the very reversal of these habitual and seemingly fixed constructed norms of White normality and hegemony (or all-embracing power) are reversed – if only in part. The first can become last and the last become first.

Those who are used to having their perspectives construed as at best ‘second best’, and are often completely demonized and without worth, are usually the ones who see the truths of the exercise with greater clarity, and are usually some time in advance of their more powerful and privileged peers. When the facilitator stands before the participant and asks repeatedly, ‘Are you sure you want to choose that favourite meal? Are you really, really sure? The standard meal is ever so sophisticated and I am sure you would like it much better than your perfectly nice, I am sure, favourite meal’, most Black folk know that type of discourse like a form of hypnotic mantra.

As a Black British-born citizen, I have grown up with the allegedly ‘well-intentioned’ rhetoric of integration ringing in my ears, which has sought to convince me that my own cultural heritage and ethnically derived practices were somehow deficient and lacking sophistication. In the politely veneered climate of British racism, this form of effortless cultural superiority is not spelt out in the visceral and polemical terms that have characterized the USA. Rather, within the British context the politeness of the rhetoric has sought to disguise the underlying ethnocentric and patrician arrogance of White institutional power.

The experience of marginalized peoples in the context of the exercise is one that attempts to mirror the dynamics and realities of many societies in the West. Many of us have been on the receiving end of subtle and not so oblique forms of cultural superiority at the hands of White elitism. Black cultural forms, at once exotic or commercially rewarding, are also significantly less aesthetically pleasing or august than the material practices of White power. While some of the normal power imbalances are reversed within the reflective processes of the exercise, it is important that I also report that the experiential dynamics of the participative framework also contain an inbuilt ambivalence in the actions of the various players.

Althou...