1

INTRODUCTION

The basic situation

The central Asiatic Pamir region was, until well into the last decades of the nineteenth century, one of the least explored areas of the world. Apparently poor in resources and at first strategically unimportant, the high mountain country had remained, until the beginning of the ‘Great Game’ around 1870, at the periphery of historical events. The defence capabilities of its inhabitants may have contributed to the fact that neither the Chinese, the Hellenic Bactria, the Islamic expansion forces, the Mongols under Ghengis Khan and his successors, nor even the Moghul rulers, could (or would) bring the Pamir under their direct control. Even when in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the Emirate of Bukhara and the Afghani kingdom took possession of parts of the Pamir, it hardly constituted an annexation as such but rather a nominal rule, more or less confirmed by the tribute delivered by the otherwise independent local lords.

The first concrete reports on the Pamir available in Europe were probably from Marco Polo, who at least crossed the highlands on his voyage to the Great Khan of the Mongols from 1273 to 1274 (Lentz 1933b: 1–31). After the Venetian, no European returned to the region until Father Benedict Goez in 1603, who, however, failed to leave a detailed description and therefore added nothing to our previous knowledge (see p. 86). Thereafter, for almost two and a half centuries, the Pamir remained of no interest at all to Europeans until Lieutenant Wood of the Indian Navy delivered the first detailed report of this area in 1841. A Journey to the Source of the River Oxus is about a ride in the eastern Pamir in 1838 in order to search for the source of the Pyandsh (also to be found in the literature as Pjansh, Pandsh, etc.) that is also the Oxus of Antiquity (Wood 1872). Despite a few treatises in geographical circles, the journey initially had few consequences, and the Pamir and its population remained unnoticed for some decades more.

This situation changed dramatically when, in the late 1860s, indications of Russian expansion into central Asia became apparent to British India. At the same time a weak point on their northern border in the Hindu Kush was diagnosed and, after some preliminary research, the British realised with some surprise that the Pamir region represented, in terms of global politics, a no-man’s land between China, Russia and British India. In consequence, the following years witnessed increasing competition between the British and the Russians, at first in the exploration of the so-far geographically practically unknown Pamir region. This was followed by 25 years of fighting over spheres of influence and borders whose value was perceived according to imaginary or actual security interests: the so-called ‘Great Game’ had begun and would occupy British Indian and Russian politicians for almost three decades. Ironically at the end of 1895, and after considerable trouble, almost exactly the same borders were established as had already been suggested in 1873. However, exploration of the region contributed greatly to filling out the ‘white stain on the map’.

Thanks to the ‘Pamir Convention’ of 1895, the border between British India and Tsarist Russia was definitively set along the artificial partition line of Wakhân (see Chapter 3). The result was that, after a few years in which old frictions between Afghanistan and the Russian protectorate of Bukhara over parts of the Pamir slowly subsided, political and scientific interest in the Pamir declined. The Great Game was over and the emergence of the Soviet Union in 1917 turned an apparently uninteresting area into a practically unreachable one. Thus, although small-scale studies in and about the Pamir were still conducted, the region remained – barring a few Russian, German and one or two French expeditions – once more outside any sphere of interest, specialist circles excepted (Figure 1.1).

This situation changed once more when the first signs of a second Great Game appeared. By 1979 the Pamir had already been turned by Soviet forces into a secondary deployment point for the occupation of Afghanistan. But it would be another decade or more before the Pamir, or rather the former Soviet and present Tajik Gorno-Badakhshan, made it once again onto the front pages of the international press. With the fall of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan declared its independence on 9 September 1991. Over the following years, frictions emerged between individual political or rather regional power- and interest-based factions in the country that ultimately resulted in a devastating civil war. This really only ended in 1997.

Already brought to the edge of economic collapse by national independence, the impact of the war on Tajikistan was to cause a complete implosion of the economy and a humanitarian catastrophe of far greater proportions than in any of the other former Soviet republics. The fact that the ‘opposition’, which after losing the fight for the capital Dushanbe continued the war partly from Afghanistan and partly out of Gharm and Gorno-Badakhshan, was controlled by Islamic forces immediately attracted Western attention. In fact, from the end of 2001 Tajikistan became a deployment point for the US in its fight against international terrorism in its Afghan guise of the Taliban and al-Qaîda. This war is in reality nothing other than the continuation of the fight for the oil reserves of Central Asia, which had already been introduced at the beginning of the 1990s when the US still expected support from the Taliban (see Rashid 2002).

The humanitarian catastrophe that had already begun to develop in Tajikistan in 1992 undoubtedly reached its regional peak in the Pamir region of the Autonomous Oblast of Gorno-Badakhshan (Gorno-Badakhshanskaja Avtonomnaja Oblast = GBAO)1 from 1993 onwards. In order to appreciate the scale of the catastrophe, some brief background is required. The high valleys of the Pamir and the deep-cut valleys of the Pyandsh and its inflows have supported a small Indo-European (Indo-Aryan) mountain folk for at least 3,000 years. These people, after centuries of oppression and internal fighting, had by 1990 finally achieved a minimal state of wealth, first through integration into the Tsarist empire but more particularly through Soviet improvements after the Second World War. Yet this wealth was not entirely due to their own diligence, but included substantial transfer payments from the Soviet central government as well. Consequently, in 1993 only 10–20 per cent of Gorno-Badakhshan’s food needs were still produced locally.

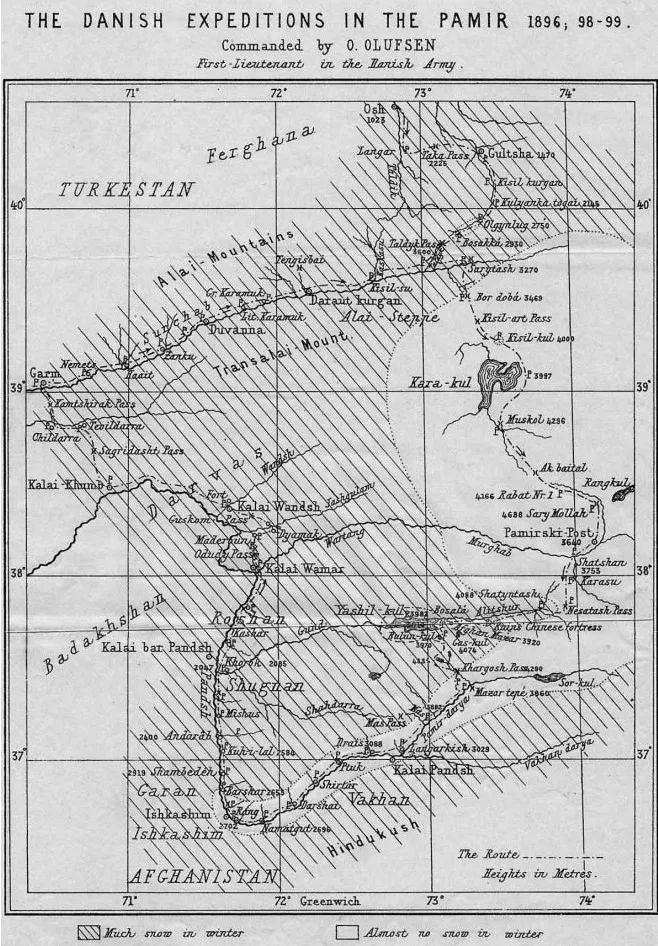

Figure 1.1 Map of Badakhshan, under Afghan, Bukhara and Russian dominion, 1896–9 (Olufsen 1904).

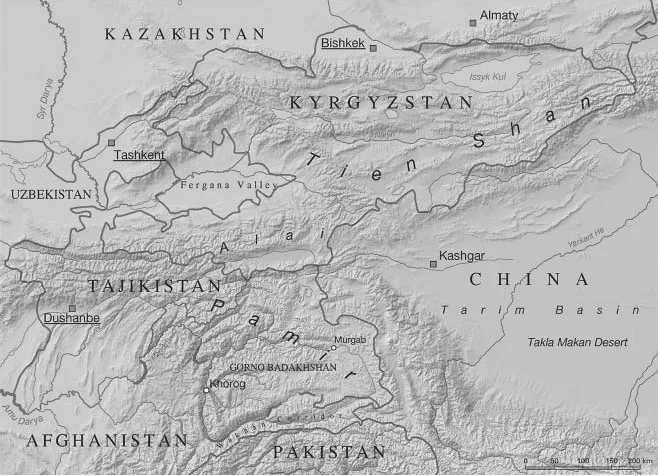

Moreover, the 180,000 or so mountain people, as well as several tens of thousands of refugees from the civil war, were effectively cut off from the rest of Tajikistan in the winter of 1992–3. The only direct route from Dushanbe through the Tavildara (Gharm) valley and over the passes of the Darwâs range to Khorog, the capital of GBAO, had been bombed in several places so that, apart from beaten tracks, every sort of direct connection to the Pamir region was cut. A third-class road through Kulyab along the Afghan border to Darwâs was equally unusable due to a landslide and military blockades. Thus until 1998 the only feasible route led through Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan (Ferghâna valley, Osh) and then the Murghâb (Pamir highlands) to Khorog, in a detour of 1,400 km (see Figure 1.2).

An open road would definitely have made the provision of humanitarian help more feasible, yet in 1993 direct support from the central government would hardly have been possible. Apart from the fact that Gorno-Badakhshan had found itself on the wrong side in the war, the economic plight in the rest of Tajikistan was anyway very severe. For example, it was supposedly not rare for 11- to 12- year-old girls to be sold for a sack of wheat (see Bruker 1997: 3). Consequently only nine – according to other sources seven – per cent of the previous supply of food reached Gorno-Badakhshan from the rest of Tajikistan. Gorno-Badakhshan therefore found itself in a situation similar to that of a ‘lost world’ in an unreachable region of the planet.

A glance at the people’s pre-existing situation may provide a better understanding of the gulf that now confronted them. Between 1950 and 1990, a backward region of central Asia had been brought, for various reasons2 and with substantial effort and at enormous cost, to a level of material wealth at least five times greater than that of neighbouring Pakistan, China and Afghanistan. Even though there existed substantial differences in income between a sovkhoz director and a simple worker in Gorno-Badakhshan, the average standard of living of most families was substantial. Every third household owned a car and almost all families had a TV set. Our interview partners (teachers for example) talked about learning holidays they had taken in the 1970s and 1980s in far-off areas of the Soviet Union and even in Eastern Europe. Each larger town had its own high school and hospital. For a rural region, the proportion of academics to the general population was exceptional. Even in the smallest villages, German (at least) was taught as a second language, while cinemas were already to be found in middle-sized villages. Plays by Schiller and Goethe were performed alongside those of Soviet poets such as Gorki – not only in the capital, Khorog, but on tour in provincial towns as well.

Figure 1.2 Area map of Tajikistan, Gorno-Badakhshan and neighbouring countries, 2003. Reprinted with permission of the author. Copyright Markus Hauser, the Pamir Archive.

Agriculture was mechanised as much as possible under local conditions (slopes, small scattered fields) and the most important workers in the sovkhozes and kolkhozes were fully trained agronomists as well as mechanical and agricultural engineers. In contrast, only 100 m away on the Afghan side of the Pyandsh, Stone Age tools were still in use. Almost all the houses had electricity, many of them running water as well. In the space of one generation, heating and cooking went from relying on wood to using electricity or coal. In Khorog there were cheap rental apartments with bathrooms and central heating. In other words, even though the population had no civil freedoms in the Western sense, people enjoyed, even according to modern standards, relatively happy and materially secure lives, especially after certain religious as well as other social freedoms were accorded in the 1980s.

The civil war destroyed everything, even though national independence and the end of subventions from Moscow had already sowed the seeds for material collapse. Although in 1992 and 1993 some food products, a little clothing and a few spare parts and fuel still arrived from central Tajikistan, by 1994 these flows had ebbed to an irrelevant trickle so that by 1995, when I arrived in Khorog to evaluate German participation in the humanitarian actions of the Aga Khan Foundation, regional and individual reserves had been exhausted. In the area of agricultural production and in the upkeep of the infrastructure, this meant that for want of spare parts and fuel hardly any tractors could still run, and thus practically all the industries in Khorog had come to a standstill. Neither the factories nor governmental institutions paid wages and, indeed, until the introduction of the Tajik rouble (TJR), there wasn’t even a currency. Bundles of Russian roubles were worthless, not just because of inflation but also because there simply was nothing left in the markets to buy.

City children who had previously been clothed and cared for in the secondary schools had to go in rags, whereas village people who were used to working with books began to sew primitive boots out of untanned leather. In one village we met a young widow with four children who, in the autumn, owned no more than two blankets. The winter, with its temperatures of –25°C was already approaching. Everything in the house had already been used up or exchanged against food. A few potatoes had come from supportive neighbours who barely had anything themselves. The concrete paving around the city blocks and in the squares of Khorog had been wrenched up to plant potatoes. In the parks of the capital and in backyards, barley was sown or herb beds planted. The fact that young men drifted in search of work and asked their elders for help in building an ox plough only showed how much the economy had collapsed. It also indicates that people had begun to see their situation clearly and no longer regarded it as a temporary lull.

The ‘Agricultural Reform’ programme that, starting in 1996/7, was supposed to lead to privatisation of agriculture and a production revolution, at least confirms this view. This was in strong contrast to the views of individual former high government and Communist Party functionaries who on the one hand lived on humanitarian help while on the other still believed in 1998 that the whole catastrophe was really only a temporary lull. In all seriousness, they insisted to us that help from Russia would be coming soon and that the socialist production system therefore need not be changed in any way. Without outside humanitarian help, practically none of those living in GBAO could have survived after 1993. Naturally, emigration out of Pamir would have been possible, but where would the people, who in part had just escaped the civil war in Tajikistan, have gone to?

Tajikistan seemed to have been forgotten by the international community. Apart from a few million dollars from the European Union and a few other donors, practically no support was provided by the rich countries of the West. It was truly fortunate for the inhabitants of GBAO that the Aga Khan, as head of the Ismaili religious community, intervened with an extensive assistance programme. Traditionally, the Pamiri in the eastern districts of Roshân, Shugnân, Ishkashim and Wakhân are Shiites, belonging to the subdivision of the ‘Seven Imâm-Shia’ (see Chapter 6). Although their relations with their religious leader in Bombay, India had been violently cut off under Stalin, perestroika during the 1980s had allowed a cautious rapprochement to take place. In 1993, the imâm, as the Ismailis call their leader, took equal responsibility for the Shiites and Sunnites of Pamir and introduced emergency measures through the Aga Khan Foundation in Geneva. These measures were later built up into a development programme.

The first task was to transport basic food products over 700 km via Kyrgyzstan and through the Murghâb into the side valleys of the Pyandsh, for which an enormous flotilla of trucks was rented. Further measures included providing agricultural inputs and cultivation counselling, as well as developing new agricultural land by building irrigation canals and privatising land ownership as the basis for increasing productivity. Since providing for over 230,000 people was too expensive even for the Aga Khan Foundation, a call for help was sent out to the international community. Among other agencies, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) announced it was ready to finance part of the humanitarian action. The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (German Technical Cooperation, or GTZ) was, as executing agency, charged to evaluate the humanitarian measures.

Study methods

Together with a staff member of the GTZ, I was able to travel to Pamir for such an evaluation for the first time in May 1995. The trip itself was already time-consuming. The flight landed in Tashk...