eBook - ePub

Calming the Brain

Benzodiazepines and Related Drugs from Laboratory to Clinic

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Calming the Brain

Benzodiazepines and Related Drugs from Laboratory to Clinic

About this book

This book covers the entire field of research in the area of minor tranquillizers and its application to current clinical practice in the treatment of anxiety and insomnia. These drugs are principally the benzodiazepines and related drugs with a similar mechanism of action, such as zolpidem and zopiclone. The molecular mechanism of action of benzodiazepines is described, focussing on the interaction of these drugs with the different isoform of the GABAA^O >receptor, and the consequences of this for brain function. Recent advances in this knowledge have provided a framework for defining the physiochemical nature of the interaction between such drugs and their receptor protein, and thus pave the way for the design of new anxiolytic and hypnotic drugs. The animal models available for evaluating the potential of such new therapeutic agents in the treatment of anxiety and insomnia are discussed. Furthermore, understanding of the physiological regulation of the GABAA receptor may provide insights into the aetiopathology of these diseases. The clinical use of benzodiazepines and related drugs in the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, epilepsy and as anaesthetics are explored. The advantages and limitations of such treatments are discussed, and the impact of drugs evaluated. A chapter is devoted to the issue of independence, the clinical pertinence of tolerence and dependence, and evaluates treatment options that may minimise the risk of dependence.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Calming the Brain by Adam Doble,Ian Martin,David Nutt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Pharmacology1

The story of modern tranquilliser drugs

BEFORE BENZODIAZEPINES

The origins of synthetic tranquilliser drugs

Although herbal medicines have been used throughout history for the treatment of what would now be considered anxiety disorders and insomnia, the advent of chemically derived drugs prescribed on the basis of a biological model of brain function and dysfunction can be identified as the introduction of bromides by Sir Charles Locock, president of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1865. Bromide salts were recommended in any condition in which the ‘calming of the brain’ was thought to be desired, for example epilepsy, anxiety, mania and insomnia.

Bromide salts were thought to replace chloride salts in the body, and thus influence chloride ion homeostasis and hence the excitability of the nervous system. Interestingly, this is rather a dirty way of doing exactly what modern benzodiazepine drugs do so selectively, namely, affecting the permeability of chloride ion channels in nerve cells and promoting neuronal inhibition.

Bromides are unsatisfactory sedatives and no longer used to any extent due to the availability of more suitable drugs. They have effects on chloride homeostasis on other organs than the brain, notably the heart and the kidney, and, since they are not readily eliminated from the organism, accumulate readily and provoke an intoxication.

Later in the nineteenth century, chloral hydrate and paraldehyde were introduced as sedatives, principally as sleeping draughts. The use of paraldehyde was indeed restricted to such use, since it makes the breath smell unpleasant. It is a long-lasting sedative drug which can produce a ‘hang-over’ effect the morning after use. Paraldehyde has all but disappeared from modern therapeutic practice. Chloral hydrate, which is better tolerated, is still, however, used to some extent, and has indeed enjoyed somewhat of a renaissance in the last fifteen years following widespread, if not always justified, publicity of the potential evils of benzodiazepine use.

The age of barbiturates

Barbituric acid was first synthesised by Adolph von Bäyer in 1864. Although this compound is biologically inactive, its derivatives were the first potent synthetic sedative drugs to be prepared. The first of these was diethylbarbituric acid in 1903, followed by phenobarbitone in 1912. These drugs rapidly acquired popularity for the treatment of epilepsy, for their calming effect in anxious subjects and for inducing sleep. The use of barbiturates (as well as bromides) increased enormously during World War I, when these drugs were widely distributed in the trenches for their calming effects, and used extensively to treat shell-shock.

After World War I, the barbiturates became the mainstay of sedative therapy, replacing the older drugs, and this remained the case up until the 1960s. A variety of different barbiturates were synthesised in the early part of the century. These newer drugs, such as pentobarbitone, amylobarbitone and secobarbitone, were more potent and had a quicker onset of action. These different barbiturates became used for different purposes, with longer-acting barbiturates, such as phenobarbitone, being used in the treatment of epilepsy, and shorter-acting agents such as amylobarbitone in the management of anxiety and insomnia. Ultra-short-acting barbiturates, such as thiobarbitone found a lasting prosperity as anaesthetic induction agents, until very recently, when they have been superseded by agents such as propofol.

There are many problems with the use of barbiturates which renders them dangerous. One of the most important is their potent induction of cytochrome P450 enzymes in the liver. As well as thereby inducing their own metabolism, leading to dose escalation, they will stimulate the metabolism of numerous other drugs. As well as this metabolic tolerance that develops during chronic barbiturate use, there is also a pharmacodynamic tolerance rendering the brain less sensitive to their sedative effects. These properties lead to regular increases in the quantities of drug administered, with the concomitant risks associated with barbiturate exposure, and hamper the process of stopping treatment.

Another major problem with barbiturates is their abuse liability. Addiction to their sedative effects is frequent, and leads to long-term dependence and difficulty in interrupting treatment. Sudden withdrawal from chronic barbiturate use can be dangerous, leading to a rebound excitation of the nervous system, manifested as a confusional state, or in extreme cases as convulsions. Recreational use of barbiturates was relatively frequent in the 1960s, and has recently seen something of a revival.

Finally, and most importantly, in overdose, barbiturate consumption can be fatal, due to terminal central nervous system depression and resulting respiratory arrest. When these drugs were the standard treatment for anxiety and insomnia, accidental death from overdose, as well as suicide, were frequent. Marilyn Monroe and Jimi Hendrix both went to early graves following a fatal overdose of barbiturates.

The use of barbiturates in the treatment of insomnia and generalised anxiety disorder is now very limited, since their replacement by benzodiazepines, which, generally speaking, neither cause liver enzyme induction nor kill in overdose. Long-acting barbiturates are still, however, sometimes used in the treatment of epilepsy, since benzodiazepines are not usually of lasting benefit in this indication.

A REVOLUTION IN PSYCHIATRIC PHARMACOTHERAPY

During the 1950s, innovative and highly efficacious chemical therapies were introduced for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. These advances revolutionised therapy, generated an important emulatory effort by medicinal chemists searching for new psychoactive drugs, and provided the tools and inspiration for a reappraisal of our understanding of the central nervous system in terms of neurotransmitter function, which remains the accepted paradigm today.

In 1952, Delay and Deniker (Delay et al, 1952) reported the calming effects of chlorpromazine, the first phenothiazine derivative, in hospitalised schizophrenic patients. This was the first time that any drug treatment had been shown to be of use in this population and led to a dramatic reduction in the number of chronically institutionalised psychotic patients, allowing them to be cared for in the community, and in many cases, resume active independent lives.

The introduction of chlorpromazine was followed by the discovery of the antidepressant effects of iproniazid (Loomer et a1, 1957) and of the Rauwolfia alkaloid reserpine for the treatment of schizophrenia (Weber, 1954). All these breakthroughs were essentially serendipitous, the drugs in question having been originally developed for other uses. Nonetheless, it demonstrated clearly for the first time that dramatic therapeutic progress in psychiatry could be achieved with drugs, and stimulated a burst of activity from the nascent modern pharmaceutical industry. As a result, many new sedative drugs appeared on the scene during the rest of the 1950s. These included a variety of other phenothiazine derivatives, haloperidol, meprobamate, glutethimide, methaqualone, chlormethiazole and the benzodiazepines. In parallel, the first generation of tricyclic anti-depressant drugs were discovered.

By the end of the decade, virtually all the major classes of modern psychoactive drugs had been discovered. Although there have been certain ameliorations or additions to the therapeutic armoury, such as the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of depression, and of buspirone for the management of generalised anxiety disorder, these have been modest in terms of pharmacological novelty. It is striking that the last forty years have witnessed so little progress compared to the previous decade, despite the huge resources invested in pharmaceutical research in psychiatry over this period.

Although most of the new psychiatric drugs were originally intended for the treatment of schizophrenia, it became apparent by 1960 that many of them were of little use in this indication, although they were beneficial in neurotic anxiety. This led to a subdivision of sedative drugs into major versus minor tranquillisers: major tranquillisers, such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol, are of use in major psychoses (ie schizophrenia) and often have neurological side-effects that would not be acceptable in less severe pathologies. This group would correspond to what are known as antipsychotics today. Minor tranquillisers are, generally speaking, not efficacious in schizophrenia and these drugs are used for the treatment of anxiety disorders and other neuroses.

This division of sedative drugs was replaced by a nosological classification during the 1960s, based on the psychiatric condition that they are supposed to treat. Thus, these drugs are classified as antipsychotics, antidepressants, antimanic drugs, anxiolytics and hypnotics. This classification remains in vogue today.

THE BENZODIAZEPINE ERA

Discovery of benzodiazepines

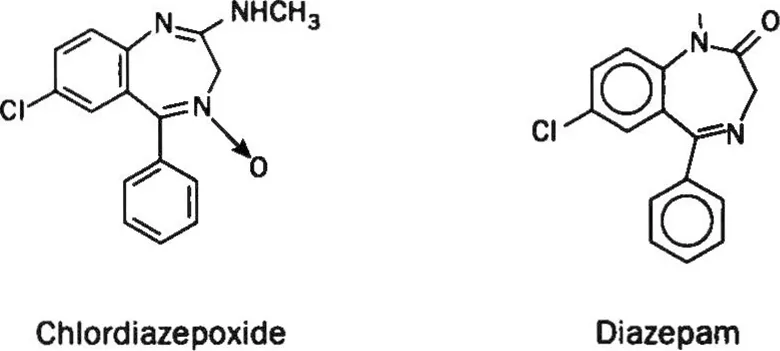

Benzodiazepines were discovered quite serendipitously. Following on the heels of chlorpromazine, chemists at Hoffmann-La Roche in Basel were trying to develop new major tranquilliser drugs. The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Figure 1.1), was synthesised quite unintentionally, and its chemical structure was originally incorrectly assigned (Sternbach, 1979). This compound had potent biological activity, the original paper describing ‘a very marked and unique taming effect on ... agitated animals’, as well as sedative and muscle relaxant properties (Randall et al, 1960). This distinguished chlordiazepoxide from other known psychoactive drugs, such as chlorpromazine and pheno-barbitone. Its discoverers noted some similarities with meprobamate, although chlordiazepoxide seemed to be considerably more potent.

Figure 1.1 Structures of chlordiazepoxide and diazepam.

Chlordiazepoxide was then rapidly evaluated in clinical trials, first of all in schizophrenia. It was noted that, even though devoid of proper antipsychotic activity, chlordiazepoxide dramatically improved symptoms of anxiety in these patients. A subsequent study in what we would now call generalised anxiety disorder showed remarkable efficacy (Tobin and Lewis, 1960). The investigators concluded that ‘chlordiazepoxide constitutes a most interesting development which makes possible successful treatment of patients with the aforementioned conditions (anxiety and tension states), who heretofore have been refractory to all other modalities of therapy’.

Chlordiazepoxide was subsequently marketed for the treatment of anxiety disorders in 1960, under the trade name Librium. According to Sternbach (1979), only thirty months elapsed between the first observations of the pharmacological effects of chlordiazepoxide in animals and its marketing. The highly successful career of the benzodiazepines in the world’s pharmacopoeias was thus launched.

The discovery and comm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 The story of modern tranquilliser drugs

- 2 Interaction of the benzodiazepines with the GABAA receptor

- 3 Structural characterisation of the GABAA receptor

- 4 Functional characterisation of the GABAA receptors

- 5 Structures of benzodiazepine recognition site ligands

- 6 Behavioural pharmacology

- 7 Pharmacokinetic determinants of clinical activity

- 8 Benzodiazepine drugs in sleep disorders

- 9 Benzodiazepines as anxiolytics

- 10 Benzodiazepines: Anticonvulsant and other clinical uses

- 11 Conclusions

- Index