- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Representation and Processing of Spatial Expressions

About this book

Coping with spatial expressions in a plausible manner is a crucial problem in a number of research fields, specifically cognitive science, artificial intelligence, psychology, and linguistics. This volume contains a set of theoretical analyses as well as accounts of applications which deal with the problems of representing and processing spatial expressions. These include dialogue understanding using mental images; interfaces to CAD and multi-media systems, such as natural language querying of photographic databases; speech-driven design and assembly; machine translation systems; spatial queries for Geographic Information Systems; and systems which generate spatial descriptions on the basis of maps, cognitive maps, or other spatial representations, such as intelligent vehicle navigation systems.

Though there have been many different approaches to the representation and processing of spatial expressions, most existing computational characterizations have so far been restricted to particularly narrow problem domains, usually specific spatial contexts determined by overall system goals. To date, artificial intelligence research in this field has rarely taken advantage of language and spatial cognition studies carried out by the cognitive science community. One of the fundamental aims of this book is to bring together research from both disciplines in the belief that artificial intelligence has much to gain from an appreciation of cognitive theories.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Neat Versus Scruffy: A Review of Computational Models for Spatial Expressions

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. The Evolution of the “Neat”

Table of contents

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Neat Versus Scruffy: A Review of Computational Models for Spatial Expressions

- 2 On Seeing Spatial Expressions

- 3 Time-Dependent Generation of Minimal Sets of Spatial Descriptions

- 4 A Computational Model for the Interpretation of Static Locative Expressions

- 5 Generating Dynamic Scene Descriptions

- 6 A Three-Dimensional Spatial Model for the Interpretation of Image Data

- 7 Shapes From Natural Language in VerbalImage

- 8 Lexical Allocation in Interlingua-Based Machine Translation of Spatial Expressions

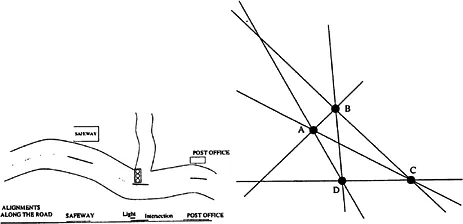

- 9 Schematization

- 10 Toward the Simulation of Spatial Mental Images Using the Voronoï Model

- 11 Generating “Mental Maps” From Route Descriptions

- 12 Integration of Visuospatial and Linguistic Information: Language Comprehension in Real Time and Real Space

- 13 Human Spatial Concepts Reflect Regularities of the Physical World and Human Body

- 14 How Addressees Affect Spatial Perspective Choice in Dialogue

- 15 Spatial Prepositions, Functional Relations, and Lexical Specification

- 16 The Representation of Space and Spatial Language: Challenges for Cognitive Science

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- Contributors

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app