- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Analytical Chemistry Refresher Manual

About this book

Analytical Chemistry Refresher Manual provides a comprehensive refresher in techniques and methodology of modern analytical chemistry. Topics include sampling and sample preparation, solution preparation, and discussions of wet and instrumental methods of analysis; spectrometric techniques of UV, vis, and IR spectroscopy; NMR, mass spectrometry, and atomic spectrometry techniques; analytical separations, including liquid-liquid extraction, liquid-solid extraction, instrumental and non-instrumental chromatography, and electrophoresis; and basic theory and instrument design concepts of gas chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography. The manual also covers automation, potentiometric and voltammetric techniques, and the detection and accounting of laboratory errors.

Analytical Chemistry Refresher Manual will benefit all laboratory workers, water and wastewater professionals, and academic researchers who are looking for a readable reference covering the fundamentals of modern analytical chemistry.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Analytical Chemistry Refresher Manual by John Kenkel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Analytic Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION TO ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY

1.1 IMPORTANCE OF ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY

We begin this refresher on analytical chemistry with the following quotation from an editorial which appeared in a recent issue of Chemical and Engineering News, a publication of the American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C.

“This should be a golden age for chemists. And in many ways it is. An unending progression of new instruments and computers continues to accelerate the pace of chemical research. Determinations that once took years and were the stuff of doctoral theses can now be done routinely overnight. Applications of chemistry to interdisciplinary areas are multiplying both the scope of chemical research and the range of the chemists’ contributions to the public good. The intellectual contributions of chemists to the understanding of nature remain exciting, rewarding, and boundless. The industries that chemists have created remain basically sound and progressive. The role of chemists in handling health and environmental problems is as vital as ever and growing.”*

While Mr. Heylin’s statement precedes an editorial on the critical state of chemistry as a profession in today’s world, it could just as easily precede an editorial on the current and future challenges that face analytical chemists today. It is truly a golden age. Instrument and computer manufacturers are producing analytical machines that are ever-increasing in power and scope. Sophisticated analytical determinations are indeed becoming routine. Analytical chemistry now touches more interdisciplinary areas and plays a greater role in the multiplication of the scope of the chemical science in general than ever before. The intellectual contributions of analytical chemists to the understanding of nature, to the chemical industries, and to the sciences of health and the environment are, to be sure, exciting, rewarding, sound, progressive, vital, and growing.

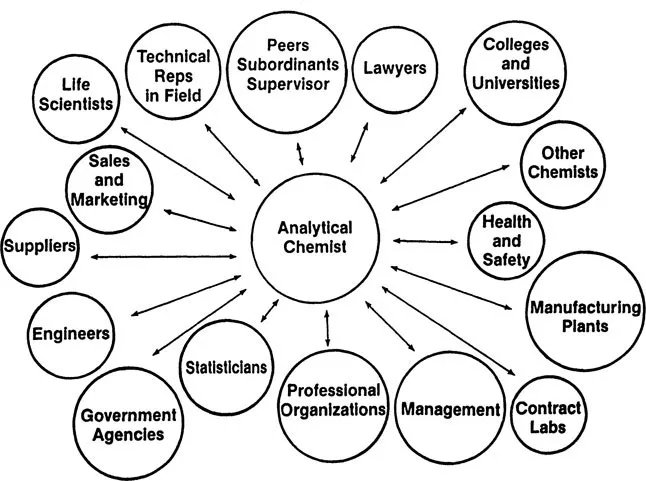

The most intriguing adjective Mr. Heylin uses, however, is “boundless.” Such an adjective in effect says that there is no limit to the scope of the discipline. This word describes modern analytical chemistry perhaps better than any other. Today, we expect analytical chemists to be a vital link in an extraordinary number of diverse fields. Industries that manufacture chemicals, pharmaceuticals, food products, paints, polymers, plastics, indeed almost any consumable product we can identify, utilize analytical chemists for quality assurance and for the research and development of new products. Environmental and health scientists today rely heavily on analytical chemists for rapid and accurate analysis of air, water, food, soil, plants, waste, and biological samples for potentially harmful chemicals. Agricultural scientists, to a large extent, rely on analytical chemists for the analysis of feeds, fertilizers, water, soil, plants, and biological samples for chemical additives and residues. Medical doctors, and thus the general public, have come to rely on analytical chemistry for an accurate analysis of blood, urine, skin, and other biological tissue and fluids. Analytical chemistry has found its way into such fields as veterinary science, archaeology, farming, and space travel. The recent controversies surrounding the Shroud of Turin (purported burial cloth of Jesus Christ) and its analysis indicates that even religion is within its scope. The modern principles and applications of analytical chemistry in today’s world are as important and as relevant to our existence as any other field that exists. Figure 1.1 presents an illustration of the dependence of various professional individuals and groups on the services that an analytical chemist renders.

The purpose of this text is to provide readable and timely descriptions of fundamental analytical laboratory processes starting with the very basic premises upon which all chemical analyses depend, that of the precision and accuracy of measurement, the fundamentals of sampling, and the thought processes involved in the planning and execution of the actual lab work itself.

1.2 PRECISION VS ACCURACY

Analytical chemistry is the science dealing with the determination of the chemical makeup of real-world material samples, with the major objective often being the numerical expression of the quantity of a component present in that sample. The accuracy of this expression is obviously very important. Analysts should therefore always be asking themselves if there is any reason to doubt the accuracy of their results. They must give some thought as to what may be the causes of inaccurate results. Errors on the part of the analyst himself or of the equipment or chemicals used are obvious causes. There may be many potential sources of such error in a given experiment, some of which can be determined (determinate errors) and some of which cannot (indeterminate errors).

Determinate errors are errors which are known to have occurred. They can arise from contamination, wrongly calibrated instruments, carelessness, etc. They can be avoided by exercising careful laboratory practices and technique. If it is determined that such an error occurred, then one obviously cannot trust the answer to be accurate.

Indeterminate errors, however, are impossible to avoid. They are “random” errors; errors which either were not known to have occurred or were known to have occurred, but could neither be taken into account, nor avoided. They are often errors which occur each time a particular analysis is run. Such errors can determine the predicted quality of the results, such as the sensitivity and detection limits of a given experiment. The error in reading a meniscus and the error associated with an instrument readout are examples of this type of error. These errors must be dealt with by statistics and the laws of probability. One way is to repeat a given analysis or procedure a number of times and use statistics to determine whether the results are precise. The determination of a “confidence interval” is often the result of a statistical analysis. (For example, the concentration of nitrate in a water sample may be expressed as 5.4± 0.2 ppm. The confidence interval is thus 5.2-5.6 ppm.) We consider precise data as having a high probability of being accurate.

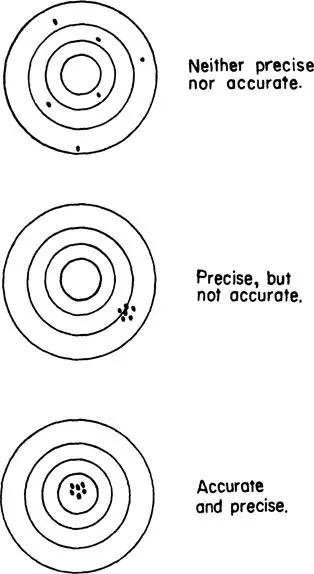

The two terms “precision” and “accuracy” are often misrepresented. Accuracy refers to the “correctness” of a given measurement or result. That is, does the measurement (or measurements) come close to what the correct answer is or what it is expected to be? A “control” sample is often run alongside the unknowns as a check on accuracy. Precision does not necessarily relate to accuracy. Precision refers to how well a series of identical measurements on the same sample agree with each other. Figure 1.2 represents a classical illustration of the difference between accuracy and precision. While precision is not necessarily synonymous with accuracy, it is often taken to indicate accuracy, unless a control indicates otherwise or unless there is known to be a factor which inherently affects accuracy on a continuous and constant basis. Chapter 13 presents more information on data quality and methods of handling laboratory data.

1.3 TERMINOLOGY

The basic terminology associated with analytical chemistry and analytical laboratory work is important and may be foreign to persons who have not been associated with such laboratory work in preparation for their jobs. We thus present a small glossary of terms in this section. Other important terms specific to particular analyses are given elsewhere in this book and can be found in the index.

Chemical Analysis | This is the determination of the chemical composition or chemical makeup of a material sample. |

Qualitative Analysis | The determination of what substances are present in a material sample, usually without the need or desire to determine quantity of these substances. |

Quantitative Analysis | The determination of how much of a specified substance is present in a material sample. |

Quantitation | This is the determination of quantity, as in the quantitative analysis above. |

Quantification | This is another word for quantitation. |

Quantitative Transfer | A transfer of a chemical or solution from one container to another, making sure that every trace of this chemical is in fact transferred. |

Analyte | This is the substance being analyzed for in an analytical procedure. This can be an element, a compound, or an ion. |

Assay | This is another word for chemical analysis. |

1.4 FUNDAMENTALS OF MEASUREMENT

In the analytical chemistry laboratory, many measurements are made, and the accuracy of these measurements obviously is a very important consideration. Different measuring devices give us different degrees of accuracy. A measurement of 0.1427 g is more accurate than a measurement of 0.14 g simply because it contains more digits. The former (0.1427 g) was made on an analytical balance, while the latter was make on an ordinary balance. A measurement recorded in a notebook should always reflect the accuracy of the measuring device. It does not make sense to use a very accurate measuring device and then record a number that is less accurate. For example, suppose a weight on an analytical balance was found to be 0.14g. It would be a mistake to record the weight as 0.14 g, even if you know personally that the weight is 0.14 g. Presumably, there are other people in the laboratory using the notebook, and your entry will be construed as to contain only two digits. The following examp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Author

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction to Analytical Chemistry

- Chapter 2 Basic Chemical Analysis Tools — Description and Use

- Chapter 3 Solution Preparation

- Chapter 4 Wet Methods and Applications

- Chapter 5 Instrumental Methods — General Discussion

- Chapter 6 Molecular Spectroscopy

- Chapter 7 Atomic Spectroscopy

- Chapter 8 Analytical Separations

- Chapter 9 Gas Chromatography

- Chapter 10 High Performance Liquid Chromatography

- Chapter 11 Electroanalytical Methods

- Chapter 12 Automation

- Chapter 13 Data Handling and Error Analysis

- Index