eBook - ePub

Train Your Gaze

A Practical and Theoretical Introduction to Portrait Photography

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Focusing on the presence of the photographer's gaze as an integral part of constructing meaningful images, Roswell Angier combines theory and practice, to provide you with the technical advice and inspiration you need to develop your skills in portrait photography.Fully updated to take into account advances in creative work and photographic technology, this second edition also includes stunning new visuals and a discussion on the role of social media in the practice of portraiture.Each chapter includes a practical assignment, designed to help you explore various kinds of portrait photography and produce a range of different styles for your creative portfolio.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Train Your Gaze by Roswell Angier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Photography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 ABOUT LOOKING

SCIENCE INTERPRETS THE GAZE IN THREE (COMBINABLE) WAYS; IN TERMS OF INFORMATION (THE GAZE INFORMS), IN TERMS OF RELATION (GAZES ARE EXCHANGED), IN TERMS OF POSSESSION (BY THE GAZE, I TOUCH, I SEIZE, I AM SEIZED). . . . BUT THE GAZE SEEKS: SOMETHING, SOMEONE. IT IS AN ANXIOUS SIGN; SINGULAR DYNAMICS FOR A SIGN: ITS POWER OVERFLOWS IT.

ROLAND BARTHES1

You are alone with your subject. The room is silent. Neither of you is talking. You stare, concentrating on minor variations of facial expression, body language, gesture. You move slowly, carefully. The camera is mounted on a tripod. The subject is stationary, but her eyes follow you as you move from side to side. Occasionally, one of her hands drifts downward toward a pocket or upward toward her face. She closes her eyes for a moment, reopens them. An eyebrow shoots up, as if to register a sudden thought.

Now. You squeeze the bulb at the end of the cable release, exposing a frame. You advance the film to the next frame. You wait for something else to happen, a facial expression or minor gestural event. The nervous tension you’ve been feeling, from not speaking to each other for what seems like a long time, is starting to subside. You are now almost in a trance. You take another picture. You advance the film again. You take another picture. You have fallen into the circle of your own gaze. You’re in fascination time.

CREATING SILENCE

In the late 1960s, Richard Avedon published a series of portraits in Rolling Stone called “The Family.” The pictures were of powerful people, mostly men. The subjects were evenly lit by ambient light, without a hint of shadow, posed in Avedon’s signature setting, against stark white backdrop paper. They seemed uneasy, many of them uncertain of what to do with their hands, some of them seeming to be collapsed inward on themselves but nonetheless determined to face the camera.

Looking at these portraits, one feels the silence as a tangible presence. It was rumored that Avedon did not speak to his subjects while he was shooting. They were ushered into his studio by an assistant and told to align their feet with a mark on the floor. The camera, an imposing 8" × 10" view camera mounted on a tripod, had been focused in advance, using an assistant as a stand-in for the subject. For the entire session, according to legend, the photographer would walk around the room, tethered to the camera by a long cable release, staring. After each exposure, an assistant would change the film holder, and the staring would resume. The result was a series of portraits in which the subject’s own presence was engulfed by the intensity of the photographer’s gaze. Sometimes the subject would stare back aggressively, but there was never any doubt about who was in control.

Avedon used a similar procedure in “In the American West,” in which he photographed drifters, miners, housekeepers, factory workers, inmates, cowboys, itinerant preachers. The subjects were social types, carefully chosen for the ways in which they represented the old frontier culture of America. In the pictures they often look haunted or intimidated; in some of them, a hint of defiance is evident. Only a single subject—a Navajo rodeo cowboy—smiles.

These photographs communicate the sense that the subjects are hanging on to their identities by a thread. Avedon achieves this effect largely by relying on the overpowering presence of the camera. Whatever they may suggest of the social fabric, his portraits are not documentary. They are not intended to be dispassionate or objective; they are certainly not friendly or compassionate. They are aggressive personal statements. In an introductory comment to this work, Avedon said that he thought all portraits, especially his own, were “opinions.” The photographer’s eye here does not seek merely to represent. Its goal is to persuade. Its nature is predatory and confrontational.

In the early days of photography, when emulsions and lenses were slow just about the only thing the camera was good for was confrontation: the creation of an image in which the subject was required to squarely face the camera and to hold still for a long exposure. Being photographed was a ceremony that lent a special quality to the resulting image, one that is hard to replicate with modern equipment. To the extent that Avedon’s portrait work has a rigorous ceremonial feeling, it is because of its affinity with the daguerreotype esthetic.

It is possible to make confrontational images with modern film and imaging devices. Modern cameras loaded with fast film (or digital cameras with a high ISO setting) can easily produce one kind of stillness: they can freeze motion with a fast shutter speed. But for the subject to produce an effect of profound motionlessness, the photographer must revert to the set of conditions imposed on the daguerreotypist. The subject must not only be told to remain motionless, but to be quiet.

Silence is a required condition for fascination. First and foremost, the photographer must be quiet, relinquishing the need to keep the subject amused with reassuring banter. This behavior is markedly different from the chatty masquerade that characterizes commercial portrait studios, where the photographer’s job is to produce an image of the subject that has a smoothly socialized, gregarious mask.

Maintaining silence is a different kind of masquerade. Not speaking may or may not be uncomfortable. It may result in a quiet power struggle, or it may become a seduction. The end result is bound to contain evidence of the kind of interaction that occurred between photographer and subject. Whatever the outcome, the picture will not feel like a moment caught on the fly.

Fig 1.1

The Kiss of Peace, 1867 Julia Margaret Cameron

The Kiss of Peace, 1867 Julia Margaret Cameron

THE LOOK IN THEIR EYES

Julia Margaret Cameron’s “Kiss of Peace” (fig. 1.1) is about looking. The image shows a woman and a girl, presumably mother and daughter. As in Avedon’s pictures, with their assertively blank backdrops, there is no suggestion of location here. The subjects inhabit an undisclosed space. There are no individuating details in the environment. Unlike Avedon’s subjects, these figures are dressed in a nondescript fashion that looks vaguely ancient, but that belongs to no specific time or place. The viewer is asked to read this image in terms of bare essentials. Who are these people? What are they doing? What is being exchanged between them? Where do we, as viewers, fit in?

The composition suggests the late-19th-century cultural value of female modesty, indicated by the averted gaze. Mother and daughter show us their profiles. They do not confront us, and they do not confront each other. The daughter’s eyes float downward, in the general direction of her mother’s breast.

The mother’s gaze provides a surprise. If we do not look too carefully, we might get the impression that her attention is focused completely on her daughter. In fact, her left eye is directed outward, toward but not at us. Violating the basic rule of the profile, in which the subject betrays no awareness of being looked at, the mother shows her awareness of an intrusive presence. The direction of her look suggests an attitude of cautious interception. She is ready to defend or protect. This awareness alters the intimacy of the moment. It is as if she is attempting to leach our attention away from her daughter, to interrupt the photographer’s gaze, as well as our own. There is tension here between photographer and subject, faintly resembling the moment of concentrated tension that Avedon habitually seeks.

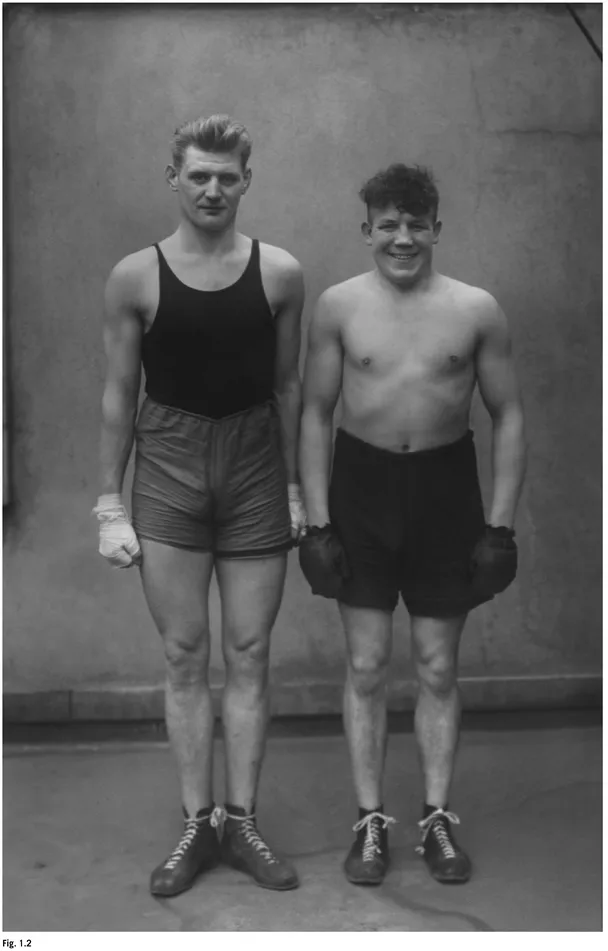

August Sander’s portrait of boxers (fig. 1.2) shows two men unguardedly staring into the camera. Their gazes are open but noncommittal. They are not engaged in

Fig. 1.2

Boxers, 1929 August Sander

Boxers, 1929 August Sander

a power struggle with the photographer or cautiously assessing the presence of an outside observer.

Sander did not seek out the revelatory moment or pounce on the transitory facial expression. His subjects usually look at us with utter equanimity. They are never startled. Their eyes appear to have nothing to hide. Their stance is settled. Sander’s portraits are not opinions, in the sense that Avedon used the word. His objective was to create an even-handed inventory of social types (a topic discussed in more detail in Chapter 7).

What was interesting to Sander was the way his subjects inhabited a spectrum of socially defined roles. He sometimes referred to his subjects as “archetypes.” Adrian Vargas, a professional boxer from San Diego, had this to say about “Two Boxers”:

Going to the gym, you see people all laughing and joking, then you see one keeping by himself, smiling. [In the photograph] you see a man on the right, and he’s just smiling. Those are the type of people you have to think about the most. Those are the ones I fear, the ones with smiles on their faces, just all to themselves. Those are the ones that pack a deadly punch. The man on the left, he looks calm, he’s ready to fight. His hands are like fists, he’s ready to go.2

What is interesting about the two boxers is their different fighting styles, which, along with their obvious physical differences, reveal their identities. Neither Vargas, the fighter, nor Sander, the photographer, is interested in what lies beneath the surface, in the recesses of the men’s psyches. Sander is interested in the subtle variations of the archetype, the small variations in the way each occupies his boxer persona.

The context of this portrait is important. The year is 1929. The boxer on the left looks Aryan; the boxer on the right might be Jewish. At the time, it would have taken some daring to circulate a photograph like this in Germany. The Third Reich wouldn’t take power until 1933, but the Nazi Party had published its 25-point party program in 1920, and had publicly declared its intention to segregate Jews from Aryan society.

Sander's first book, The Face of Our Time, was banned in 1936, and the printer’s plates were destroyed. Sander’s offense was that he refused to promote Nazi values through photography. He did not view photography as a vehicle for making judgments or as a conduit for partisan values of any sort. His portrait of the two boxers is evidence of these convictions. (Sander’s ambition to create a “portrait atlas” of German society is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.)

WHAT LIES BENEATH

Julia Margaret Cameron was one of the first photographers to state that she had psychological intentions. In her journal, she wrote that she sought to capture “the greatness of the inner, not the outer man” in the photographs she took of prominent Victorian intellectuals.

To do so, she had a technician remove some of the elements from her camera lens, reducing its resolution. The resulting images were soft in focus, a far cry from the sharpness of the daguerreotype portrait.

Cameron was more interested in metaphor than in description. The blurry quality of her photographs and their absence of crisp detail require us to imagine some of the missing information. They require us to assume an attitude of interpretation.

What information does “The Kiss of Peace” provide for us to interpret? The mother’s mouth does not actually make contact with her daughter’s cheek; her lips are closed, immobile, silent. The title of the photograph seems to contradict what it shows. The guarded quality of the mother’s look, discussed previously, as well as her body language, has ruptured the feeling of tranquil intimacy the viewer may have initially thought was the subject of the picture. Instead of serenity, there is irony. The title may have been intended as a bit of a ruse, a camouflage the viewer is meant to see through. Cameron was one of the first photographers to assert herself as an artist, declaring that her motivation for making pictures was to penetrate beneath surface appearances. It makes sense that her efforts also went beyond her desire to reveal ephemeral aspects of the individual psyche, as in her portraits of famous Victorian men, and led her to insinuate some commentary on a cultural stereotype, while seeming to simply render it without critical distance. The stereotype here is that of the docile Madonna, ever available to the leisurely inspections of her viewers’ admiring gaze. The subtle attitude of resignation in the mother’s expression, and even in the tilt of her head, could be read as a sign of the burden involved in maintaining this masquerade.

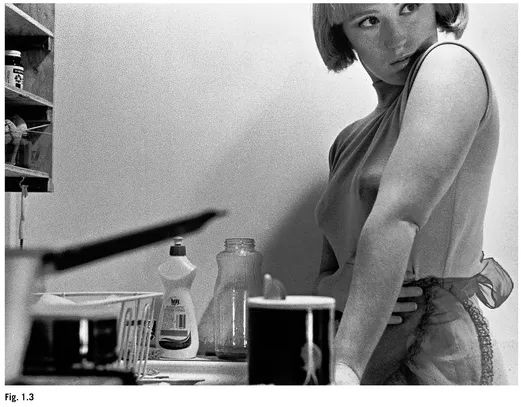

Like Cameron, Cindy Sherman is concerned with the spectacle of female identity and issues of femininity, albeit in a way that is more overt and thorough. “Untitled Film Still, #3” is part of a series of portraits in which the artist impersonates various archetypes of femininity. Many of the images depict 1950s film noir–like narratives, such as sexual triangles in which a designing woman looks for a way out of an oppressive relationship with an abusive partner.

This image presents a woman in a tight top standing at a kitchen sink. There is a suggestion of dirty dishes. A sharply focused bottle of detergent intersects the out-of-focus handle of a pot that juts into the frame like an arrow, pointing directly at the woman’s upraised left breast. The woman’s gaze is directed out of the frame, as if she is looking toward someone else in the room, someone out of the camera’s field of view, possibly her husband/captor.

Fig 1.3

Untitled Film Still, #3, 1977 Cindy Sherman

Untitled Film Still, #3, 1977 Cindy Sherman

There ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER 1 ABOUT LOOKING

- CHAPTER 2 PORTRAIT/SELF-PORTRAIT, FACE/NO FACE

- CHAPTER 3 AT THE MARGIN: THE EDGES OF THE FRAME

- CHAPTER 4 TREMORS OF NARRATIVE: PORTRAITS AND EVENTFULNESS

- CHAPTER 5 YOU SPY: VOYEURISM AND SURVEILLANCE

- CHAPTER 6 PORTRAIT, MIRROR, MASQUERADE

- CHAPTER 7 CONFRONTATION: LOOKING THROUGH THE BULL'S EYE

- CHAPTER 8 BLUR: THE DISAPPEARING SUBJECT

- CHAPTER 9 FLASH

- CHAPTER 10 FIGURES IN A LANDSCAPE

- CHAPTER 11 DIGITAL PERSONAE

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

- PICTURE CREDITS