eBook - ePub

Wildhood

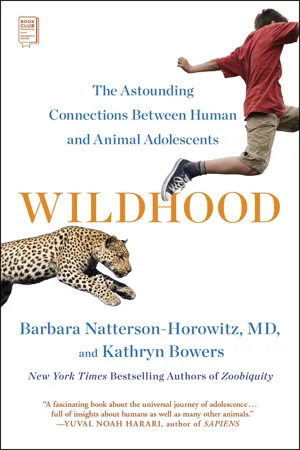

The Astounding Connections between Human and Animal Adolescents

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wildhood

The Astounding Connections between Human and Animal Adolescents

About this book

A New York Times Editor’s Pick ** People Best Books ** Publishers Weekly Most Anticipated Books ** Chicago Tribune 28 Books You Need to Read Now **

“It blew my mind to discover that adolescent animals and humans are so similar…I loved this book!” —Temple Grandin, author of Animals Make Us Human and Animals in Translation

A “vivid…and fascinating” (Los Angeles Times) investigation of human and animal adolescence and nature’s guide to growing up from the New York Times bestselling authors of Zoobiquity.

Harvard evolutionary biologist Barbara Natterson-Horowitz and animal behaviorist Kathryn Bowers studied thousands of wild species searching for evidence of human-like adolescence in other animals. With a groundbreaking synthesis of animal behavior, human psychology, and evolutionary biology, their research uncovered something remarkable: the same four high-stakes tests shape the destiny of every adolescent on planet Earth—how to be safe, how to navigate social hierarchies, how to connect romantically, and how to live independently. Safety. Status. Sex. Self-reliance.

To bring these challenges to life, the authors analyzed GPS and radio collar data from four wild adolescent animals. Will a predator-naïve penguin become easy prey? Can a low-born hyena socialize his way to a better life? Did a young humpback choose the right mate? Will a newly independent grey wolf starve, or will he become self-reliant? The result is a game-changing perspective on anxiety, risky behavior, sexual first times, and leaving home that can help teenagers and young adults coming of age in a rapidly changing world.

As they discover that “adolescence isn’t just for humans” through “rollicking tales of young animals navigating risk, social hierarchy, and sex with all the bravura (and dopiness) of our own teenage beasts” (People), readers will learn that in fact, this volatile and vulnerable phase of life creates the basis of adult confidence, success, and even happiness. This is an invaluable guide for parents, teenagers, and anyone who cares about adolescence and the science of growing up, who will find “the similarities between animal and human teenagers uncanny, and the lessons they have to learn remarkably similar” (The New York Times Book Review).

“It blew my mind to discover that adolescent animals and humans are so similar…I loved this book!” —Temple Grandin, author of Animals Make Us Human and Animals in Translation

A “vivid…and fascinating” (Los Angeles Times) investigation of human and animal adolescence and nature’s guide to growing up from the New York Times bestselling authors of Zoobiquity.

Harvard evolutionary biologist Barbara Natterson-Horowitz and animal behaviorist Kathryn Bowers studied thousands of wild species searching for evidence of human-like adolescence in other animals. With a groundbreaking synthesis of animal behavior, human psychology, and evolutionary biology, their research uncovered something remarkable: the same four high-stakes tests shape the destiny of every adolescent on planet Earth—how to be safe, how to navigate social hierarchies, how to connect romantically, and how to live independently. Safety. Status. Sex. Self-reliance.

To bring these challenges to life, the authors analyzed GPS and radio collar data from four wild adolescent animals. Will a predator-naïve penguin become easy prey? Can a low-born hyena socialize his way to a better life? Did a young humpback choose the right mate? Will a newly independent grey wolf starve, or will he become self-reliant? The result is a game-changing perspective on anxiety, risky behavior, sexual first times, and leaving home that can help teenagers and young adults coming of age in a rapidly changing world.

As they discover that “adolescence isn’t just for humans” through “rollicking tales of young animals navigating risk, social hierarchy, and sex with all the bravura (and dopiness) of our own teenage beasts” (People), readers will learn that in fact, this volatile and vulnerable phase of life creates the basis of adult confidence, success, and even happiness. This is an invaluable guide for parents, teenagers, and anyone who cares about adolescence and the science of growing up, who will find “the similarities between animal and human teenagers uncanny, and the lessons they have to learn remarkably similar” (The New York Times Book Review).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Wildhood by Barbara Natterson-Horowitz,Kathryn Bowers in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781501164712Subtopic

Psychologie du développementPART I

SAFETY

During wildhood, humans and other animals are predator naive. Their inexperience attracts attackers and exploiters who see them as easy prey. Predator training—learning to recognize and deter individuals with violent intentions—may save their lives and prepare them to be more confident adults.

Chapter 1

Dangerous Days

South Georgia Island rises out of the Atlantic Ocean about a thousand miles off Antarctica. If you’d visited there on December 16, 2007, you might have witnessed a defining moment in the life of a young king penguin named Ursula. On that Sunday, Ursula turned away from her parents. She waddled down to the beach with a squawking crowd of her identical-looking peers. Then suddenly she leapt into the frigid water and swam away from home at full speed, without looking back.

Until that moment, Ursula had never ventured more than a hundred yards from where she’d been born. She’d never played in the surf. Not once had she attempted to swim in the open ocean. Ursula had never even fed herself. Up to this point, every meal had been provided by her parents (partially digested and regurgitated straight into her open mouth).

As a fluffy nestling warm under her parents’ feathers, Ursula had weathered freezing temperatures and intense winds. Defended by Mom and Dad, she’d survived attacks by skuas, fearsome predatory seabirds that tear apart baby penguins to feed to their own young offspring. Growing up, Ursula, like all king penguins, had a secret language with her parents, unique calls that belonged only to the three of them. For king penguins, parental care lasts a full year and during that time the small family is a tight trio. Mom and Dad care equally for their young, trading off the roles of caregiver, breadwinner, and security guard.

Lately, though, things had changed. Ursula had been shedding the soft brownish down of chick-hood. Sleek black-and-white adult feathers had begun popping through the shaggy patches of her baby plumage. Her squeaky juvenile peeps had deepened into the buzzing honks that make penguin colonies sound like giant, conductorless kazoo orchestras.

Ursula’s transformation wasn’t just physical. Her behavior too was suddenly different. Overtaken by restlessness, she’d begun wandering farther from her parents. During the day she gathered with other adolescents in chattering penguin gangs. Her edginess has a special scientific name: zugunruhe, which is German for “migration anxiety.” Zugunruhe has been studied in birds, mammals, and even insects that are on the brink of moving away from home territories. Sleeplessness—fueled by shifts in arousing adrenaline and sleep-inducing melatonin—often accompanies zugunruhe in animals. A human might describe the feeling of zugunruhe with words like “excitement,” “dread,” and “anticipation.”

Until that particular Sunday in December, Ursula’s increasing wanderlust had been kept in check by an urge to return each night to the safety of Mom, Dad, and the rest of the rookery. But today was different. Resplendent in her smart new tuxedo, hyped up on adrenaline, and buzzing with her peers, Ursula moved toward the water’s edge. Shoulder to shoulder, the jostling adolescents milled, gazing out to sea and glancing back at home. No longer chicks, not quite adults, they paused on the brink of a great unknown.

Like fledgling humans leaving to make their way in the outside world, Ursula faced four great tests. She would quickly have to learn to feed herself and find safe places to rest. She’d need to navigate the social dynamics of her penguin group. She would have to learn to court and communicate with potential mates. And she’d be doing it all without her parents, alone in the middle of the open ocean.

But none of these penguin milestones could happen if Ursula weren’t alive. The first great test is to stay safe. Failing this ends a young animal’s future before it can even start. Ursula’s first challenge was to come face-to-face with death—and survive.

For adolescent penguins dispersing every year from South Georgia Island, the first day away from home is literally sink or swim. Like adolescent animals all over the world, young adult penguins are inexperienced and underprepared. They don’t realize predators are dangerous until it’s too late. Even if they spot danger, they might not know what to do next. Lacking know-how and unaccompanied by protective parents, adolescents are targets. They’re the definition of easy prey.

Ursula’s first experience in the water would also be her first encounter with what lay beneath it. And what lay beneath was monstrous. Lurking offshore penguin breeding grounds are predators with jaws so big they can easily swallow a basketball. Picture those massive jaws, lined with teeth like a tiger’s, speeding toward a penguin’s tennis ball–sized head. That’s the maw of one of Earth’s elite hunters: leopard seals. A hydrodynamic half-ton of explosive muscle, leopard seals excel in penguin killing. With cool precision, they grab the birds and smack them back and forth on the surface of the water to flay off the feathers. It’s a grisly performance worthy of a sushi chef, and leopard seals dispatch ten or more penguins at every meal. Like their feline namesakes, leopard seals are ambush hunters, meaning they hide and wait for prey. Arranging themselves along coastlines like underwater mines, leopard seals skulk along the edges of ice banks, just out of sight. Sometimes they masquerade as flotsam, quietly floating in the waves, the better to surprise their unwary victims. Dispersing adolescent penguins must run this gauntlet of death and come out the other side. If they don’t jump in, they can’t grow up. But if they don’t make it past the leopard seals, as well as the pods of predatory orcas, the first day of the rest of their lives will also be their last. Getting past the danger is a high-stakes test for the penguins who must pass or fail permanently.

If you’d been there to witness this do-or-die moment, you might have noticed that Ursula and two of her peers sported an accessory that distinguished them from their classmates. Stuck to their backs with black tape were tiny transponders, programmed to transmit never-before-gathered information about where penguins go on the day they leave home and in the weeks after. The surprising results would turn out to entirely reframe what biologists knew about penguin behavior. Led by Klemens Pütz, the scientific director of the Zurich-based Antarctic Research Trust, the multinational investigation included researchers from Europe, Argentina, and the Falkland Islands. Some of the funding came from ecotourists, who as part of their donation got to name the radio-tagged birds.

That’s how we know that a penguin named Ursula jumped in the South Polar sea on Sunday, December 16, 2007. The signals from her tracking device pinpointed exactly when she waddled to the beach, pre-plunge. Of the eight penguins that Pütz’s team tagged on South Georgia Island that season, three departed that day—Ursula and two others named Tankini and Traudel—along with a crowd of their adolescent peers.

Like high schoolers on graduation night, Ursula and her cohort—the South Georgia Island king penguin class of 2007—were physically grown and ready to leave. But, much like their human counterparts, with little adult experience in the real world they were still behaviorally immature.

Suddenly, they dove. An arch of her back, a sweep of her flippers, and Ursula was speeding straight into the zone of danger. As for her penguin parents—and the biologists tracking her—all they could do was stand by and watch as she swam away.

VULNERABLE BY NATURE

Of the thousands of adolescent king penguins that plunge into predator-patrolled waters every year, many don’t make it out alive. Some years survival has been as low as 40 percent. Other years are less deadly, although exact numbers are hard to calculate. No matter what, the first days, weeks, and months after fledging are exceedingly risky for all penguins.

It’s sobering to recognize how dangerous life on Earth is for adolescent and young adult animals. In the wild they crash, drown, and starve more often than their adult counterparts. With less experience, they’re pushed into jeopardy by older, bigger peers. They’re preferentially targeted and killed by predators.

Fortunately, when human adolescents leave home, they don’t share the extremely high mortality rate of fledgling penguins. However, adolescent humans do suffer much higher rates of traumatic injury and death compared with adults. A nearly 200 percent increase in mortality is seen between childhood and adolescence in the United States. Almost half of all deaths among adolescents are the unintentional and tragic result of accidents such as motor vehicle collisions, falls, poisonings, and gunfire.

Adolescents drive faster than adults and are generally more reckless. They have the highest rates of criminal behavior and are five times more likely to be the victims of homicide than adults thirty-five or older. Other than toddlers (who stick fingers into sockets) and adults with jobs in electricity-related industries, adolescents have the highest rates of fatal electrocution. Adolescents and young adults fifteen to twenty-four also have the highest rates of death by drowning, other than infants and toddlers under the age of five. Compared with other populations, they’re afflicted in great numbers by suicide and by the onset of mental illnesses and addictions. And adolescents are far more likely to binge-drink themselves to intoxication and death than older adults.

Dangers vary by social class and geography, but globally, human adolescents develop half of all new cases of sexually transmitted infections. They’re the most vulnerable to sexual assault. Worldwide, the leading cause of death in fifteen- to nineteen-year-old girls continues to be pregnancy-related complications.

Adolescence can be harrowing, but the biology that contributes to the danger and vulnerability also inspires creativity and passion, as Robert Sapolsky, the Stanford neuroscientist and evolutionary biologist, so vividly describes in his book Behave:

Adolescence and early adulthood are the times when someone is most likely to kill, be killed, leave home forever, invent an art form, help overthrow a dictator, ethnically cleanse a village, devote themselves to the needy, become addicted, marry outside their group, transform physics, have hideous fashion taste, break their neck recreationally, commit their life to God, mug an old lady, or be convinced that all of history has converged to make this moment the most consequential, the most fraught with peril and promise, the most demanding that they get involved and make a difference.

FROM PREDATOR NAIVE TO PREDATOR AWARE

Ursula, of course, didn’t know the grim odds before her. Even if she did, perhaps the magical thinking of youth would have made her believe she was chosen for survival. But, in fact, all king penguins are naive when they set off. And we use that word deliberately, without judgment. It’s a wildlife biology term for a specific state of development: inexperienced, unsuspecting young animals leaving home for the first time are “predator naive.”

For a gazelle, being predator naive means not knowing what a cheetah smells like or how it moves. For adolescent salmon, it means not yet knowing that cod hunt more slowly at night, relying on smell and hearing to find their prey, and that during the day, when they can see, cod strike more quickly. Sea otters are predator naive when they encounter great white sharks for the first time, and predator-naive marmots cavort obliviously outside their burrows, even when coyotes are nearby. For tiny West African Diana monkeys, being predator naive means not yet having the ability to discern the different hunting sounds made by eagles, leopards, and snakes. They cannot predict whether an attack will come from above, below, or around a tree limb.

Predator naive is exactly what human adolescents are too when they enter the world with little experience. They don’t recognize what’s dangerous. Even when they do, they often don’t know what to do about it. This inexperience can be as deadly for human adolescents as it is for young penguins.

A predator-naive teen going off to a party or a young adult moving to a new city won’t have literal leopard seals waiting, but the array of dangers they may face are no less lethal: a swerving pickup truck, a drunken hazing ritual, a depressive episode, a predatory adult, or a loaded gun.

It seems tragically counterintuitive that the most vulnerable and underprepared individuals would be thrown into the riskiest possible situations. But facing mortal danger while still maturing is a fact of life for adolescents and young adults across species. It’s as true for a young sea turtle that hatches and heads into the ocean without ever meeting its parents as it is for an African elephant that is nurtured for twelve years by its multigenerational, extended family. Animals will ultimately lose parental protection and face the dangerous world on their own. They can’t remain predator naive; they must become predator aware if they are to survive. It sets up a paradox for every adolescent: to become experienced you must have experiences. Said another way: to become safe you must take risks. And notably, some risks can’t be taken—and their lessons learned—when protective parents are too nearby.

For humans, this paradox underlies a certain terror of parenthood. Parents can’t always protect their kids from danger, and sometimes can’t even alert them to it. Just as distressing, through their risk-taking, adolescents seem to bring needless danger upon themselves. Whether they’re sixth-graders testing thin ice on a pond with their friends or high schoolers masquerading as twenty-two-year-olds to get into a nightclub, adolescents frequently put themselves in danger deliberately, to the angst and occasional heartbreak of their parents. The jeopardy they seek out—reckless driving, substance abuse, careless sex—can be baffling to adults. Even when deliberate adolescent risk-taking is of the more mundane variety, like building a bonfire with friends in the woods or sneaking a ride on someone’s motorcycle, it’s the stuff of parental obsession and late-night, nauseated worrying. It’s one thing for a child to be naive to the dangers of the world. It’s quite another to know something is dangerous but underestimate the risk and invite it to come closer. Sometimes hilariously, sometimes maddeningly, and sometimes tragically, adolescents don’t just stumble into trouble; they voluntarily place themselves squarely in its path.

The behavior seems inexplicable, even contrary to the survival instinct. Taking dangerous risks that could result in death does not seem to make much sense from an evolutionary point of view. And yet, this strange behavior isn’t limited to human adolescents. Adolescent risk-taking is seen throughout the animal world. During adolescence, groups of bats taunt predatory owls, and squirrel squads scamper recklessly around rattlesnakes. Not-yet-adult lemurs climb out onto the slimmest branches, and adolescent mountain goats scale the highest ledges. Away from their parents, young adult gazelles saunter up to hungry cheetahs. Adolescent sea otters swim up to great white sharks.

One approach to understanding puzzling behavior is to look for it in other species. Examining the life histories of those animals may then reveal how the “illogical” behavior actually helps them live longer, function better, and have more offspring. For risk-taking, this means first asking: Do other animals take risks during adolescence? And then: How does that adolescent risk-taking help them?

Evolutionary biologists will recognize this approach as an application of Nikolaas Tinbergen’s famous “Four Questions.” Tinbergen, a Dutch ethologist who won the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, believed animal behavior couldn’t be fully understood by just explaining its mechanical nuts and bolts or the age in which it occurred. For him, it was always important to look for the behavior across species and determine how it was biologically beneficial. For humans it’s helpful to distinguish between the risks teens invite through naivete and the risks they seem to seek out. Both, if survived, can offer future protective benefits. By the end of Part I you’ll recognize the distinction. You’ll understand why this period of life is so dangerous for all species. And, crucially, you’ll understand why taking risks to become safe is not a paradox. It’s actually a requirement for adolescent and young adult animals on Earth.

But in order to talk about staying safe, we first must travel to the roots of terror, deep within the ancient connection between mind and body. The story of safety begins with understanding the nature of fear.

2323__perl...Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Prologue

- Part I: Safety

- Part II: Status

- Part III: Sex

- Part IV: Self-Reliance

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Reading Group Guide

- ‘Zoobiquity’ Teaser

- About the Authors

- Glossary of Terms

- Notes

- Note About the Illustrations

- Index

- Copyright