- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Of all the crimes to which Palestinians have been subjected through a century of bitter tragedy, perhaps none are more cruel than the silencing of their voices. The suffering has been most extreme, criminal, and grotesque in Gaza, where Ghada Ageel was one of the victims from childhood. This collection of essays is a poignant cry for justice, far too long delayed." —Noam Chomsky

There are more than two sides to the conflict between Palestine and Israel. There are millions. Millions of lives, voices, and stories behind the enduring struggle in Israel and Palestine. Yet, the easy binary of Palestine vs. Israel on which the media so often relies for context effectively silences the lived experiences of people affected by the strife. Ghada Ageel sought leading experts—Palestinian and Israeli, academic and activist—to gather stories that humanize the historic processes of occupation, displacement, colonization, and, most controversially, apartheid. Historians, scholars and students of colonialism and Israel-Palestine studies, and anyone interested in more nuanced debate, will want to read this book. Foreword by Richard Falk.

Contributors: Yasmeen Abu-Laban, Ghada Ageel, Huwaida Arraf, Abigail B. Bakan, Ramzy Baroud, Samar El-Bekai, James Cairns, Edward C. Corrigan, Susan Ferguson, Keith Hammond, Rela Mazali, Sherene Razack, Tali Shapiro, Reem Skeik, Rafeef Ziadah.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Apartheid in Palestine by Ghada Ageel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Beit Daras

Once upon a Land

SIXTY-SEVEN YEARS AGO, Khadija, a young, pretty woman from the village of Beit Daras woke up to a tragedy that ravaged her heart and altered her life forever. She and her two young children were evicted from their home. Abdelaziz was three and Jawad just one. The horror was etched on all of her neighbours’ tearful faces, a language and reality they shared for decades—some to this day. When her husband, Mohammed, rejoined his family in June 1948, Khadija didn’t need to ask about the fate of their home. His eyes answered her question. Beit Daras was no more.

Today, over six decades after the expulsion, Khadija still remembers the horror of the 1948 dispossession and those unhappy days. She bears witness to an ongoing present that is not much different from a tragic past—a past that has cast a dark shadow not only over her life but also over the lives of the generations that followed. All of her dreams, hopes, and good work were blown away by the savage winds of war and time. Unable to return to her home in Beit Daras, one of the villages of Gaza District under the British Mandate, Khadija was obliged to live in the greatest uncertainty about her future in one of Gaza’s eight refugee camps established by the United Nations when hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees were prevented by Israel from returning home. Across the border of Gaza—to the south in Egypt, to the north in Lebanon and Syria, and to the east in Jordan—there are currently over five million Palestinian refugees who still, like Khadija, live a life of perpetual waiting, enduring multiple hardships in their long exile (UNRWA 2013).

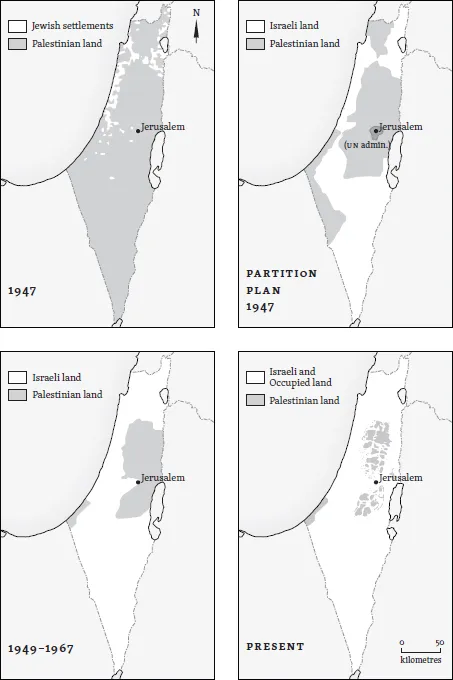

Khadija, eighty-nine, a mother of ten and grandmother of sixty-eight, now lives in tragic circumstances in the Khan Younis refugee camp. Once she owned a house, farms, and land, and she enjoyed honour, dignity, and hope. She was part of the Beit Daras commun-ity, a village that no longer exists on world maps. It has been demolished, together with over five hundred other Palestinian villages. Khadija’s tale is a story of a land that has been emptied of its people and of a people who have been separated from their land and segregated from each other—some never to be reunited. Over 70 per cent of the current population of Gaza are refugees whose stories closely approximate Khadija’s. Either they themselves or their parents or grandparents were driven from their homes in 1948. Israeli military forces systematically destroyed hundreds of Palestinian villages during and after the 1948 war, as one of six measures included in a “Retroactive Transfer” plan approved in June 1948 by the Israeli finance minister and prime minister to prevent Palestinian refugees from returning home (Badil 2009, 10). Since 1967, the population has lived under direct Israeli occupation and, for almost a decade now, in a prison effected by Israel’s blockade. This population is ghettoized in a tiny 1.5 per cent of the original territory of historic Palestine. Meanwhile, Palestinians in the West Bank are ghettoized in less than 10 per cent of the original territory of Palestine. But they, in addition, have been fragmented and forced into dozens of isolated cantons, only moving between or in and out of these with Israeli permission. Reminiscent of apartheid South Africa,[1] a humiliating and arbitrary system of checkpoints, separation walls, ID cards, and permits issued by Israel circumscribe and control Palestinians’ lives and their freedom of movement, whether to or from work or school.

The loss of Palestinian land from 1947 to present.

This chapter describes similarities in Palestinian experiences from 1948 until the time of writing, in 2014. As the story of two generations reveals, comparisons can be drawn between the present and past. History seems to repeat itself over and over; denial, however, remains the main feature of the Palestinian experience. While generational analogies can never be full, the comparison strives to shed some light on parallels whose implications should be considered when analyzing the broad historical context of the ongoing impasse in Israel/Palestine. I argue that the present situation is an extension of policies and actions carried out almost seven decades ago. Just as the forces of expulsion, destruction, segregation, and domination that initiated in 1948 have continued to intensify, so too has the steadfastness of the Palestinians. Repeated wars have destroyed the foundations of their homes, but these have failed to destroy the foundations of their nation and their identity. Despite the savage winds of war and time, the new generations still hold on tight to their long-postponed rights and dreams to return home.

Beit Daras

Situated forty-six kilometres northeast of Gaza and approximately one hour by car from Khan Younis, Beit Daras was completely destroyed by Zionist troops prior to and after the establishment of the state of Israel. The villagers, mostly peasants,[2] defended their homeland with the means they had at the time. They fought several fierce battles between March and June 1948 to save their native land. Hundreds of men and women sacrificed their lives or were massacred during these months and afterwards. Incapable of withstanding the well-equipped, trained, and more numerous Zionist military troops based in nearby Jewish settlement of Tabiyya, Beit Daras succumbed after more than four battles.

Before the village was ethnically cleansed in 1948, approximately three thousand people lived in Beit Daras; some four hundred houses, one elementary school, and two mosques stood there (Baroud 2010, 6). Virtually nothing is left today. According to historian Walid Khalidi, “the only remains of village buildings are the foundation of one house and some scattered rubble. At least one of the old streets is clearly recognizable” (Khalidi 1992, 522).

Khadija’s family was well known, respected, and wealthy. They owned hundreds of dunums.[3] In fact, they owned one-quarter of the land of Beit Daras. They grew all sorts of crops, including wheat, corn, sesame, barley, and lentils as well as cucumbers, tomatoes, and sunflowers. There were also fields for grapes and trees—apple, fig, and citrus—which provided fruit throughout the year.

In early March 1948, a few months after the passage of the UN partition resolution relating to Palestine, the Zionist leadership devised a blueprint known as Plan Dalet “to achieve the military fait accompli upon which the state of Israel was to be based” (Khalidi 1988, 8). According to Plan Dalet, “operations can be carried out in the following manner: either by destroying villages (setting fire to them, by blowing them up, and by planting mines in their rubble), and especially those population centres that are difficult to control permanently; or by mounting combing and control operations according to the following guidelines: encirclement of the villages, conducting a search inside them. In case of resistance, the armed forces must be wiped out & the population expelled outside the borders of the state” (Badil 2010). The Zionist leadership instructed the Haganah, the main Jewish underground military in Palestine, to prepare to take over the Palestinian parts assigned by the Jewish Agency. The Haganah had several units and each one received a list of villages it had to occupy or destroy and inhabitants to expel (Morris 2009, 38). Most of the villages were listed to be destroyed. Beit Daras was among them. The Givati unit drew the assignment.

According to Plan Dalet, Jewish forces were ordered to cleanse the Palestinian areas that fell under their control. Israeli historian Ilan Pappe describes this cleansing: “Villages were surrounded from three flanks and the fourth one was left open for flight and evacuation. In some cases it did not work, and many villagers remained in the houses—here is where massacres took place” (2008).

This was precisely what happened in Beit Daras during the last battle.

Fearing for the life of her young children after several fierce battles that claimed many lives, Khadija decided to spend a few nights in nearby Isdud. She intended to return in the mornings to her home and fields to work. On a sunny day in May, she felt tired and opted to take Jawad with her to Beit Daras and to leave Abdelaziz in Isdud with other family members. At sunset, she was still tired and decided to spend the night in her home. That night Zionist troops attacked the village once again. Their usual tactic was to surround Beit Daras from three sides and leave the fourth one, leading to Isdud, open. But this time they had mined the road leads to Isdud. Hearing heavy planes bombing and shooting, Khadija, carrying Jawad, searched for safety.

Bombs fell from everywhere and gunfire surrounded her. One step forward, she recalls, a bomb blast back. She was very frightened. Women and children screamed as they searched for a way out. Khadija didn’t scream, but Jawad did. Tears streamed down her face. Everyone was terrified. Some people took their animals so they wouldn’t be killed. Then the mines started to explode. Horses, cows, sheep, and people ran in different directions. Still the bombs fell. Worse was to come. Planes attacked from the sky. Bullets felt close to her head and legs. But she continued to run. She has often remarked that a gate to hell opened that day and never closed. When she reached Isdud, she knocked at the first door. When it was opened, she heard someone crying. It was Jawad. She had dropped him behind in her panic.

Late the next afternoon, after the battle had finished, Khadija returned to her village. The road to her home was littered with bullet shells and covered in blood. Many homes were blown up. More dead bodies than she could count were on the roads. Men were burying them. One of her relatives was among them. She felt her heart stop; this man was the only son in his family and was recently married with two children. The Haganah carried out a massacre in Beit Daras and then returned to their settlement.

From the early days of Nakba—the “catastrophe”—in direct violation of UN resolutions, every effort was made to prevent the return of those expelled (Flapan 1987). When Khadija’s uncle and cousin returned to Beit Daras after the last battle to fetch some food and clothes from their home, they were arrested by Haganah and imprisoned for several years. They were relatively lucky as other people from Beit Daras had been killed in the preceding weeks. The Zionist troops didn’t want anyone to return to their home, and they shot anyone they found returning. A female relative of Khadija went with a man from the village to get food from their homes and fields. While they were harvesting corn to fill their sacks, Zionist militia forces started shooting at them and the man was killed.[4]

Third Generation of Refugees

I am the eldest granddaughter of Khadija. I inherited the genes of a refugee from my father, Abdelaziz, Khadija’s eldest son. Growing up in a refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, decades after the destruction of Beit Daras, my grandmother told me the story of our village. At the time, during the 1970s, it was too dangerous even to mention the word Palestine. We were denied the right to study, read, or possess anything related to our homeland. My grandmother stepped in to close that gap of historical denial. She didn’t forget our land, contrary to the prediction of David Ben-Gurion that the old generations would die and young generations would forget (Al Awda 2012). The story of our lost village was, in the accurate words of Ramzy Baroud, “a daily narrative that simply defined our internal relationship as a community” (2008). Telling the story of her village, Khadija knew, would not bring back the dead from the grave, nor would it return Beit Daras. But telling the story would help to prevent Beit Daras from being exiled from human memory and history. It would also help us—the new generations born in the camps—to learn our history. That was her mission.

My real introduction to the horrors of life and the meaning of life, death, and home was back in 2003, during one of the many Israeli military invasions of the Khan Younis camp. The dark realities of those bleak moments struck me hard in both heart and mind as I ran in the middle of the night, carrying my son, then aged three, in search of safety. But, in Gaza, there is no place that can be called safe. Despite this reality, people under attack run because they naturally feel that staying still, while the Israeli tanks are advancing and destroying their neighbours’ homes, is to risk their lives. What intensifies that feeling is the death coming from sky—from the American-made Apaches that hover above their heads. Death, at these moments, is palpable. The barrier between life and death vanishes as a bullet streaks past my head or a shell shakes my body. It is one bullet or shell of the many menacingly zooming around me. As the tenuous nature of life is exacerbated, the will to a safe life gets stronger.

That night, fifty-five years after the destruction of Beit Daras, and the military occupation of what remains of historic Palestine, I, the third generation of Palestinian refugees, found myself carrying my son, fleeing to nowhere, and leaving the place that I regarded as home. That night, I repeated the same scenario that occurred in 1948 when my grandmother carried my dad, Abdelaziz, and my uncle, Jawad, and made her way to nearby Isdud looking for temporary safety and waiting for things settle down so that she could return to her home. That night, the Israeli military forces carried out the same old practices and the same old polices to maintain their domination over our space and souls. They surrounded the camp from three sides, destroyed the houses that they planned to destroy, and then they withdrew to their Gush Katif bloc of colonies. With each attack, more homes were demolished, more people displaced, and more atrocities committed. Furthermore, the separation fence inside Gaza also expanded, as the Israeli military swallowed more and more of what little land remained to us. More aggressive policies of massive land grab are currently taking place in West Bank, expanding Jewish-only colonies at the expense of Palestinians’ land and destroying any connectivity of people or feasibility and possibility of a viable Palestinian state.

Amid all of that horror, the memories of heated debates between my grandmother and me about my home, my village, and my homeland began to feed one another. I asked my grandmother many questions during our conversations. These were followed by more questions—questions that many of my generation also asked. Why didn’t you stay in Beit Daras and die there? Why do I have to be a refugee and live this misery? Why was I brought to this poor life in which I need to queue for food rations and second-hand clothes at UN distribution centres?[5]

During those bleak moments, I saw how woven together these disparate fragments of past and present are. They shift back and forth again and again. I’ve come also to feel how selfish I was when I was concerned only about myself—my image, my pain, my life, and my future—and never about her. How naive I was to think that her saving the lives of her children was a cowardly act. How shortsighted I was when I thought that land is more important than human life. And how dare anyone say that Palestinian mothers don’t love their children and leave them to die.

My grandmother has been separated from her land and home for many years now. Despite the passage of time, she has neither found a safe place to live nor been able to return to her home. Unlike her, on the morning following the attack on that horrible night, I could return to my family home in the Khan Younis camp. Other neighbours were also able to return to their tents that morning—shelters that could serve as their homes until they rebuilt new ones.

Pictures coming from Gaza in winter 2012 after the Israeli attack on the tiny besieged strip, as well as winter 2014 after the summer attack, showed newly homeless families sitting in their tents in the cold. The photos reminded me of my neighbours’ tents in 2003 and the tents of 1948 that were pitched before my time. That year, my grandmother spent the harsh winter in tent camps provided by voluntary organizations. The only hope for her then was the one offered by UN Resolution 194 of 1948. Article 11 of the resolution reads, “Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date.” The UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) visited the refugees’ tents to count the number of persons in each family so the agency could provide blankets. My grandmother’s extended family received fifteen blankets. It was very cold then, and the donation was very much appreciated. This past winter the Palestinians of Gaza were likewise given blankets—but without the UN resolutions.

Similarly, in 2008, Fawziya Kurd and her paralyzed husband were given a tent after their home in Jerusalem was...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I Indigenous Voices

- PART II Activist Views

- PART III Academic and Expert Insights

- Contributors

- Index

- Other Titles from The University of Alberta Press