- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

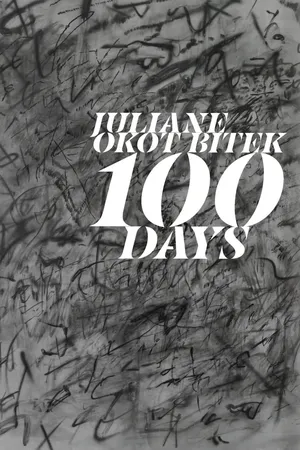

100 Days

About this book

100 days... 100 days that should not have been... 100 days the world could have stopped. But did not.

For 100 days, Juliane Okot Bitek recorded the lingering nightmare of the Rwandan genocide in a poem—each poem recalling the senseless loss of life and of innocence. Okot Bitek draws on her own family's experience of displacement under the regime of Idi Amin, pulling in fragments of the poetic traditions she encounters along the way: the Ugandan Acholi oral tradition of her father—the poet Okot p'Bitek; Anglican hymns; the rhythms and sounds of the African American Spiritual tradition; and the beat of spoken word and hip-hop. 100 Days is a collection of poetry that will stop you in your tracks. Foreword by Cecily Nicholson.

It was the earth that betrayed us first

it was the earth that held onto its beauty

compelling us to return

it was the breezes that were there

& then not there

it was the sun that rose & fell

rose & fell

as if there was nothing different

as if nothing changed

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Day 1

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Day 100

- Day 99

- Day 98

- Day 97

- Day 96

- Day 95

- Day 94

- Day 93

- Day 92

- Day 91

- Day 90

- Day 89

- Day 88

- Day 87

- Day 86

- Day 85

- Day 84

- Day 83

- Day 82

- Day 81

- Day 80

- Day 79

- Day 78

- Day 77

- Day 76

- Day 75

- Day 74

- Day 73

- Day 72

- Day 71

- Day 70

- Day 69

- Day 68

- Day 67

- Day 66

- Day 65

- Day 64

- Day 63

- Day 62

- Day 61

- Day 60

- Day 59

- Day 58

- Day 57

- Day 56

- Day 55

- Day 54

- Day 53

- Day 52

- Day 51

- Day 50

- Day 49

- Day 48

- Day 47

- Day 46

- Day 45

- Day 44

- Day 43

- Day 42

- Day 41

- Day 40

- Day 39

- Day 38

- Day 37

- Day 36

- Day 35

- Day 34

- Day 33

- Day 32

- Day 31

- Day 30

- Day 29

- Day 28

- Day 27

- Day 26

- Day 25

- Day 24

- Day 23

- Day 22

- Day 21

- Day 20

- Day 19

- Day 18

- Day 17

- Day 16

- Day 15

- Day 14

- Day 13

- Day 12

- Day 11

- Day 10

- Day 9

- Day 8

- Day 7

- Day 6

- Day 5

- Day 4

- Day 3

- Day 2

- Day 1

- Author’s Note

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Other Titles from The University of Alberta Press

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app