eBook - ePub

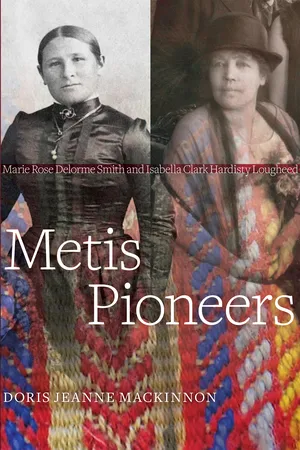

Metis Pioneers

Marie Rose Delorme Smith and Isabella Clark Hardisty Lougheed

- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Metis Pioneers, Doris Jeanne MacKinnon compares the survival strategies of two Metis women born during the fur trade—one from the French-speaking free trade tradition and one from the English-speaking Hudson's Bay Company tradition—who settled in southern Alberta as the Canadian West transitioned to a sedentary agricultural and industrial economy. MacKinnon provides rare insight into their lives, demonstrating the contributions Metis women made to the building of the Prairie West. This is a compelling tale of two women's acts of quiet resistance in the final days of the British Empire.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Metis Pioneers by Doris Jeanne MacKinnon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Being and Becoming Metis

IN ORDER TO UNDERSTAND both how Marie Rose and Isabella transitioned in a changing world, and how Canadian society has accessed some of its historical knowledge about Metis people, it is important to speak briefly about the changing focus for historians. It was only in the 1980s that scholars acknowledged that the Metis had survived the end of the fur trade era as a “people” with their own identifiable culture and distinct history. Early histories of the Metis were largely subsumed within the history of the fur trade, and most scholars saw them as an ethnic group unable to thrive beyond the fur trade. While this chapter cannot undertake a complete annotated bibliography of the rapidly changing field of Metis historiography, there are pivotal works that help explain the trends that contributed to the historical process that has enabled and assisted close case studies of Metis women such as this one, and provide opportunity for continuing this type of study.

Beginning in the 1930s with the work of Harold Innis,1 through to Arthur Ray’s work in the 1970s,2 the economy of the fur trade was the primary focus for historians. In the transitional period of Metis historiography that began in the 1970s, scholars such as Sylvia Van Kirk,3 Jennifer Brown,4 and Jacqueline Peterson5 expanded Indigenous history to focus on the role of Metis women who lived during the fur trade era. John Foster’s work on the emergence of the Metis as a distinct cultural group was also published during this period.6

The focus on fur trade company corporate cultures evolved to examinations of kinship links for Metis people, with work by scholars such as Lucy Eldersveld Murphy,7 Tanis Thorne,8 and Susan Sleeper-Smith, who also expanded the geographic focus from Red River to the Great Lakes area of what is now northwestern Indiana and southwest Michigan.9 Sleeper-Smith explored the thesis that Indigenous women who married French men actually assumed a role as cultural mediators and negotiators of change when they established elaborate trading networks through Roman Catholic kinship connections that paralleled those of Indigenous societies.10 It was evident that these women did not “marry out,” but rather that they incorporated their French husbands into a society structured by Indigenous custom and tradition.11 Thus, these Metis women did not reinvent themselves as French but rather enhanced their distinct Metis identity. Van Kirk also argued that, from an Indigenous perspective, the process of women marrying fur traders was never regarded as marrying out.12 Rather, these marriages were important means of incorporating traders into existing kinship networks, and traders often had to abide by Indigenous marital customs, including the payment of bride price.13 These scholars were able to demonstrate that Metis women made significant contributions to the fur trade. However, there has yet to be a significant number of studies that examine the important roles Metis women played in the transition from the fur trade economy to the industrialized sedentary economy that replaced it.14

More recently, scholars of Indigenous ancestry, such as Heather Devine15 and Brenda Macdougall,16 used geneaological reconstruction and biographical methodologies to examine Metis identity formation in geographic areas that expanded beyond the Red River area. Martha Harroun Foster, whose research also expanded beyond the traditional fur trade era that had previously been studied by many historians, noted that some Metis women in the Spring Creek community of Montana used kinship networks (and practices such as godparenting) as a way to consolidate more recent trade relationships to ensure their families’ prosperity, and in essence reaffirm existing Metis networks.17 The Spring Creek Metis, former fur traders, became business people in the new economy, and tended to extend their kinship networks through such practices as asking non-Metis associates and neighbours to serve as godparents for their children.18

Harroun Foster notes that as the kinship network of the Spring Creek Metis expanded, and came to include more non-Metis members, the terms the Metis used to identify themselves became more complex. Thus, terms like “breed,” once common, became more private, so that few Metis people remembered using the terms “half-breed” or “Metis” outside of the family. Yet self-identification as Euro-North American could, but did not necessarily, represent a rejection of a Metis identity or Metis kin group.19 For this group of Montana Metis, although a private Metis identity survived, that identity became increasingly complex, multilayered, and situational, but nonetheless remained rooted in the kinship networks first established as part of fur trade culture.20

In reality, for families of the Canadian fur trade that might have various “tribal relatives,” as well as Euro-Canadian family members, Metis ethnicity was often inclusive enough to encompass and accept all members of the family. Kinship links between culturally distinct groups enabled accommodation and subsequently influenced tribal politics in many geographic areas when settlement by Euro-North Americans occurred.21 Because there was very little opportunity between the late 1890s and the 1920s to publicly identify as Metis, it was not unusual for most Metis during that time to identify as either “Indian or white,” while privately nurturing a Metis identity. History confirms that it has always been an integral aspect of the Metis culture to allow a web of kinship ties to enrich rather than to destroy a sense of unique ethnicity.22 Kinship systems often allowed the Metis to sustain their identity in a safe, supportive atmosphere, even if those identities had to be enjoyed only in the private realm.

In Canada, the Metis were often forced to enjoy their identity in the private realm due, in part, to the fact that Metis identity has not always been open to individual choice. At various times in Canadian history, by way of the Indian Act, treaty negotiations and enforcement, and scrip regulations, the government determined who was “status Indian” and who was Metis. It is entirely possible that some Metis in Canada, as in the United States, found they could be “white and Métis or Métis and Indian with sincerity and apparent ease.”23 In a study of her own “French-Indian” ancestors who settled in the Willamette Valley, Melinda Jetté concluded that

they were not exclusively American, Indian, French-Canadian, or métis, but were all of these things at different times and in different places…there was a process of negotiation that went on throughout their lives…the family navigated a place for itself amidst a unique set of cultural traditions.24

Despite observations such as those by Harroun Foster and Jetté in regard to the continuity of Metis culture and identity, some scholars had previously argued that fur trade society was abruptly replaced by a new economy. The first scholar to conduct an in-depth study of Canada’s Metis people, Marcel Giraud, helped to create (in historiography) a stereotypical Metis character unsuited to function in the new economy,25 and a belief that deficiencies in Metis culture were a result of miscegenation.26 In the same way, W.L. Morton, often seen as the first regional historian of the Canadian Prairies, believed that

when the agricultural frontier advanced into the Red River Valley in the 1870s, the last buffalo herds were destroyed in the 1880s, the half-breed community of the West, la nation métisse, was doomed, and made its last ineffectual protest against extinction in the Saskatchewan Rebellion of 1885.27

Despite viewing the Metis as doomed people, Morton saw what he believed to be the “two strongly defined currents” emanating from unions between HBC men and Indigenous women, and those between the French traders and Indigenous women. However, he also acknowledged a sense of unified identity, in that “the children of both streams of admixture had bonds of union in a common maternal ancestry and a common dependence on the fur trade.”28 Nonetheless, for Morton, there was a clear break between fur trade society and that which replaced it, and there was really no place for the Metis in the new economy.

In reality, the research that forms the basis of this book confirms that there was distinct and identifiable continuity from the fur trade economy with the new sedentary agricultural and commercial economy. Furthermore, the view that Red River was unstable exaggerates the weaknesses of the community and thus underestimates the abilities of its residents and the kinship webs that extended from that community into the transitional era. By the late 1850s and into the 1860s, Red River was already becoming integrated into the wider world, and many of the Metis had adjusted to new economic opportunities and adopted characteristics of an entrepreneurial class. These entrepreneurs were found among both French- and English-speaking Metis.29 The idea that the Metis were a people “in between” two cultures, which still persists for some today, ignores the reality that the fur trade engendered its own diverse people with their own unique and diverse culture. The view that the Metis were not equipped to survive in the new economy that emerged after the end of the fur trade ignores the fact that Metis culture thrived in the capitalist institution of the Hudson’s Bay Company,30 a company that had absorbed the North West Company and established the foundations of the new order. In reality, the lessons that fur trade children learned from their Metis culture could have facilitated the transition for the majority of them had there not been other mitigating factors.31

One of the most visible early examples of continuity between the fur trade economy and the new economy was John Norquay, the Metis man who served as premier of Manitoba between 1879 and 1887.32 The main priority for Norquay’s government was to foster economic development by building railway lines, public works, and municipal institutions, as well as assuming debt for construction activity.33 While some may have seen Norquay’s defeat in 1888 as the end of the old order in Red River, Norquay was, in fact, a “creature of the new age,” given his dedication to economic development according to the principles of industrial capitalism.34 In reality, the primary reason Norquay clashed with John A. Macdonald, Conservative prime minister at the time, was not because he was a Metis of the old order, or even because he was Liberal, but because he attempted to establish a competing rail line to the Canadian Pacific Railway in order to satisfy the growing concerns of a broad cross-section of Manitoba’s population.

By 1886, near the end of Norquay’s time as premier, and just one year after the conflict in 1885, the population of Manitoba had grown substantially, from 60,000 in 1881, to 109,000.35 It is true that, by this time, many Metis had moved further west and north, where rapid settlement by newcomers only occurred after 1896. However, the reason for this exodus by the Metis had less to do with economy than with the influx of Euro-North American settlers who were less than tolerant of racial equality. In addition, the long-distance supervision by the federal government over the vast North-West Territories (and the imposition of its new land use regulations) presented challenges for all residents. Despite the challenges, many of the Metis who were forced away from Red River were able to re-establish themselves on prosperous farms along the South Saskatchewan River and in permanent settlements that featured merchants, mills, farms, and churches. This is further evidence of Metis adaptation to economic changes.36

In reality, both incoming settlers and the Metis were forced to negotiate new economic challenges, including recessions, such as that in 1882, which saw many new immigrants leave Canada. The emigrants included some Metis who went to Dakota and Montana. Out-migration continued to be a cause for concern on the prairies until the 1900s. Also, not unlike the new settlers in their struggles with the changing economy, the Metis had concerns regarding Ottawa’s policies addressing territorial rights. Widespread concern about property rights by the majority living in the area was one of the motivating factors in the political agitation that led to the armed conflicts in 1885. Although this conflict came to be viewed as a Metis uprising, in reality, Frank Oliver, editor of the Edmonton Bulletin, had argued in 1884 that “rebellion alone” would force the central government to heed concerns in the North West.37 As many have since noted, government inefficiency led many new settlers to join the initial protests that eventually culminated in the fighting in 1885.

Because the fighting in 1885 has come to be seen as an Indigenous action that arose only out of Indigenous concerns, the view that Indigenous people were unable to adjust to new economic and environmental realities persisted for some time in historiography. However, in a broadly based macro study published in 1996, Frank Tough provided solid evidence that Indigenous people were prepared to alter tradition by participating in the Euro-North American economy when mercantilism gave way to industrialism. For example, in the late 1800s, the export of new staples, such as fish, lumber, and cordwood from northern Manitoba, represented a diversification of activity for Indigneous people.38 History demonstrates over and over that, when allowed, Indigenous people were able to maintain viable economies by incorporating their labour into new resource industries and responding to new markets.39 It was because Indigenous people did not have control of the land that they remained dependent on the needs of the metropolis and on the decisions of government agents and Euro-North American business interests.40 Some historians have demonstrated that, even when Indigenous people were successful workmen, they were still not masters of their own destiny in ways that they had been when traditional territorial boundaries were respected, and in ways that Euro-North American settlers were.41

Territorial boundaries were an important component of Metis history in the North West. It is also true that Central Canadians increasingly saw land as the West’s best resource. Eventually, the practice of informal land occupancy that had been enjoyed by the Metis over vast areas of the North West gave way to a formalized system managed by the Dominion Land Survey and the free hold tenure system. Land for settlement space and resource wealth was so important to the annexationist plans...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Terminology

- Note on Sources

- Note on Names

- Introduction

- 1. Being and Becoming Metis

- 2. The Ties That Bind

- 3. Gracious Womanhood

- 4. With This Economy We Do Wed

- 5. Trader Delorme’s Family

- 6. Queen of the Jughandle

- 7. Fenced In

- 8. Many Voices—One People

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author