- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

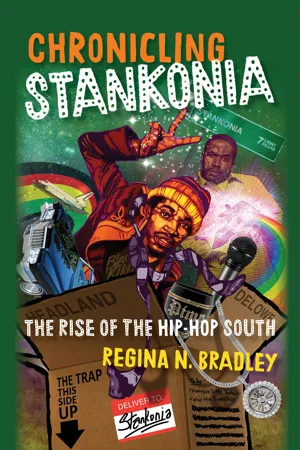

This vibrant book pulses with the beats of a new American South, probing the ways music, literature, and film have remixed southern identities for a post–civil rights generation. For scholar and critic Regina N. Bradley, Outkast’s work is the touchstone, a blend of funk, gospel, and hip-hop developed in conjunction with the work of other culture creators—including T.I., Kiese Laymon, and Jesmyn Ward. This work, Bradley argues, helps define new cultural possibilities for black southerners who came of age in the 1980s and 1990s and have used hip-hop culture to buffer themselves from the historical narratives and expectations of the civil rights era. André 3000, Big Boi, and a wider community of creators emerge as founding theoreticians of the hip-hop South, framing a larger question of how the region fits into not only hip-hop culture but also contemporary American society as a whole.

Chronicling Stankonia reflects the ways that culture, race, and southernness intersect in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Although part of southern hip-hop culture remains attached to the past, Bradley demonstrates how younger southerners use the music to embrace the possibility of multiple Souths, multiple narratives, and multiple points of entry to contemporary southern black identity.

Chronicling Stankonia reflects the ways that culture, race, and southernness intersect in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Although part of southern hip-hop culture remains attached to the past, Bradley demonstrates how younger southerners use the music to embrace the possibility of multiple Souths, multiple narratives, and multiple points of entry to contemporary southern black identity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chronicling Stankonia by Regina Bradley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnomusicology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE: THE DEMO TAPE AIN’T NOBODY WANNA HEAR

While most people consider the biggest takeaway from OutKast’s historic win at the 1995 Source Awards to be André Benjamin’s iconic declaration “the South got something to say,” the opening of Benjamin’s acceptance speech is also a theorization of the black South’s rough transition into bicoastal hip-hop and contemporary American culture at large.1 Sonically and visibly frustrated, Benjamin starts his speech: “It’s like this though. I’m tired of close-minded folks, you know what I’m saying? … We got this demo tape and don’t nobody wanna hear it.” On the surface, Benjamin’s statement suggests a familiar narrative in hip-hop: “We tryna make it and nobody would give us a chance but we made it anyway.” However, Benjamin also invokes the regional biases of hip-hop, especially by New York City artists and record labels, citing their refusal to listen to OutKast’s music—or to celebrate their win—as antisouthernness. New York’s rejection of OutKast by booing and showing disinterest sonically and culturally signified OutKast’s moniker as southern hip-hop rejects, taking root in northeast hip-hop’s inability to literally listen and make legible OutKast’s contemporary southernness.

I argue that Benjamin’s belief that “the South got something to say” is the genesis point for the hip-hop South, but his statement that OutKast is the creator of an unheard and disrespected demo tape is an articulation of the group’s subversion of rejection into an aesthetic. It is the beginning of what would pull through OutKast’s growing body of work: an incessant need to experiment with their southern blackness and expand notions of the black South past physical boundaries and the limited imaginations of nonsoutherners within and outside of hip-hop. In their discography, both Benjamin and Patton center being “OutKasted” as a working verb, a constant experiment of creative evolution and dabbling in world and culture building. Their music transitions the South from its physical limitations into a cultural concept, poking and prodding at the ways the South intersects with the identities, memories, experiences, and possibilities of black people. OutKast is an unabashed cultural investigation of black southernness that bows to nothing but the group’s own prowess. Ultimately, their work pursues the breaking of limitations about the South as a viable and vibrant space of creative reckoning with the past, present, and future.

Are You ATLien(s)?

If Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik is an introduction to contemporary Atlanta and southern hip-hop, OutKast’s second studio album ATLiens (1996) is an amplified response to their rejection at the Source Awards. Because OutKast’s centering of a southern sociocultural landscape did not and could not fully take root in the hip-hop narrative of the moment—the growing animosity between East and West Coast hip-hop communities and their differing approaches to urbanity-as-authenticity took center stage—ATLiens moves far into the future to think through the implications of hip-hop and agency in the post–civil rights South. The album’s simultaneous focus on the past—both recent and longer-standing—and present demonstrates what Alondra Nelson refers to as “past-future visions.”2 ATLiens creates a fantastic account of the migration of southern blackness on its own terms: an envisioning of the South’s future as a polytemporal space of past and present experiences. The album can be read as a speculative reimagining of a new migration, akin to the early twentieth-century phenomenon, that focuses on the black folks who stayed in the South. Instead of moving to the romanticized Northeast, OutKast imagines what would happen if black southerners moved past historical boundaries into the speculative space that could house their otherness—outer space.

ATLiens carves space for OutKast’s imagining of the hip-hop South as a possibility of futurity, pulling from historical and futuristic black aesthetics that speak to their hybridized experiences of being Southern, black, and invested in hip-hop.3 What I mean here is that OutKast was already dabbling in ideas of ascension on Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik that would be more fleshed out on ATLiens. For example, the track “D.E.E.P.” from Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik is the first introduction to OutKast as aliens. The song opens with the lines, “Greetings, Earthlings. Take me to your leader.”4 The greeting, stiff and roboticized, sonically amplifies the popular treatment of aliens in science fiction as othered and even monstrous, a stark opposition to (white) normalcy. In this sense, the alien’s greeting is both a salutation and a challenge: the alien is asking about Earth’s leadership and OutKast is responding with a searing narrative of paranoia and antiestablishment, promising both physical and psychological retorts of violence for devaluing their existence and insight. On “D.E.E.P.,” Patton and Benjamin do not shy away from the very real crises on Earth and especially in the South, referencing the AIDS epidemic, poverty, and white supremacy. The challenge to “go deep” is multilayered when grounded in hip-hop as a tool of social commentary. On the surface, OutKast asks the audience—symbolized by the alien—if they are sure they want to go deeper in listening to two southern rappers who are not fixated on the stereotypical ideas of southern blacks as backward and slow. OutKast raps about their endangered state from a southern perspective, aligning their own status as outsiders with the alien.

The appearance of an alien greeting listeners at the beginning of the track “Two Dope Boyz in a Cadillac” on the ATLiens album is an extension of OutKast’s full embrace of their moniker and experimenting with notions of southern black essentialisms. The “alien” introduced here can be read as Patton and Benjamin’s introducing themselves as “alien” and separate from bicoastal hip-hop. ATLiens is a concept album that captures the widely recognizable trope of racial displacement and repurposes it to speak to their alienation from hip-hop as southerners. The creation of “ATLiens”—natives to the city of Atlanta but also alien to those who view the city and the South as alien or foreign—is rooted firmly in a long line of southern-influenced funk artists who used space to establish self-autonomy (such as Sun-Ra, or frequent OutKast collaborator George Clinton). ATLiens is an experiment not only in OutKast’s shift in the way they aligned themselves with hip-hop but also in the evolution of their views of how their southernness could be manifested in their music. To build on a theory offered by my former student Jeff Wallace, ATLiens is suggestive of the beginning of OutKast’s hip-hop odyssey: the introduction, a prelude titled “You May Die,” is the beginning of OutKast’s journey into space, a departure from the binding parameters of Earth, the southeast United States, and hip-hop. The track suggests that there is risk in leaving the familiar, but the reward is self-autonomy. The following track, “Two Dope Boyz in a Cadillac,” is OutKast’s arrival, a subversion of the alien visiting them from “D.E.E.P.” Their bodies, like their music, are made mobile via the Cadillac, now a spaceship that falls into the musical lineage of funk artists like George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic’s “mothership.” The imagery of OutKast’s reimagined mothership pulls from the past and present, signifying upon the slave ship that brought black people to OutKast’s original homeland of the South and the trope of the funk mothership that would bring black folks and their southern sensibilities to space, the final “homeland” of infinite freedom and autonomy outside of white supremacy. The track following “Two Dope Boyz,” “ATLiens,” affirms this by asking listeners to “throw their hands in the air” if they like “fish and grits and all that pimp shit,” examples of southern culture they introduced on Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.5 This track title, like the rest of the album, solidifies and celebrates OutKast’s self-imposed exclusion and freedom from the world.

In OutKast’s imagination, the black South was no longer physically confined to the lower end of the United States. ATLiens demonstrates the South as fluid and mobile. This is most visibly demonstrated in the liner notes, which take the form of a comic book designed under the guidance of D. L. Warfield. On the cover, an illustrated OutKast is seen squared up in a fighting stance ready to battle against a backdrop of neon-colored villains as (anti)heroes. The comic itself, written by OutKast and Big Rube, is a roughly scripted battle of good and evil against the evil musical force called Nosamulli. It captures the materialization of OutKast’s rejection of bicoastal hip-hop rules. The ATLiens comic book visualizes the dirtiness of southern hip-hop and the sliding scale of time and unbound possibilities of southern identity and experience. The South as an otherworldly place pivots on the infinite possibility of time and the existence of outer space as parallel to the uncontainable and ever refreshing reservoir of southern time and memory.

OutKast’s intentional disembodiment from bicoastal hip-hop creates room for larger discussions of race, class, and identity that remain connected to past southern identities. For example, Patton’s superpower is the ability to transform into a black panther. From a historical perspective, the black panther symbolized the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Hayneville, Alabama, before its more recognizable attachment to the Black Panther Party coming out of Oakland, California.6 Additionally, in Marvel comics the Black Panther is the superhero identity of T’Challa, the king of a fictitious African country named Wakanda. Adilifu Nama’s study Super Black contextualizes T’Challa as a global southern hero, “an idealized composite of third-world black revolutionaries and the anticolonialist movement of the 1950s they represented.”7 Nama labels T’Challa as “a recurperative figure and majestic signifier of the best of the black anticolonialist movement.”8 Patton’s superpower as a black panther situates him in the larger sociocultural context of freedom and struggle associated with the South and the African diaspora. The comic book allows OutKast to refurbish their narratives of southernness associated with Atlanta while pushing past the boundaries of blackness and identity to tap into a larger global black experience. Although other hip-hop artists such as A Tribe Called Quest, Snoop Dogg, MF Doom, and GZA also use the comic-book aesthetic in their liner notes, OutKast uses the comic book as a distinguishing tool of southern agency and figurative being in hip-hop culture. The ATLiens comic book provides an interstitial space between oral tradition—a prominent form of remembrance in the South—and hard print for OutKast’s imaginative exploits to exist.

Further, OutKast signifies on the comic book as a contemporary talking-book, the trope Henry Louis Gates theorizes in The Signifying Monkey as a “double-voiced text that talks to other texts.”9 The ATLiens comic book is a double-voiced text in multiple registers: it represents the literal voice of Patton and Benjamin, it can be read as a tangible manifestation of OutKast’s awareness of themselves as southern black men (aligning with Du Bois’s theorization of double consciousness), and the comic-book form bridging hip-hop into broader areas and audiences of popular culture through the lens of regionalism.

Consider the music video for ATLiens’s first single “Elevators.” The video opens with the sounds of a pan flute and strings and shows a group of people wading through a dense forest led by OutKast. The shot then pans to a young Asian boy sitting under a tree reading the ATLiens comic book. A sample of the track’s sparse accompaniment of bass kicks, a wood block, and high hats softly plays in the background, signifying the talking drum and the announcement of an arrival. The boy’s eyes widen in interest and possibly amazement, while the video transitions into the beginning of the comic book set in a classroom and on a graduation stage for Benjamin’s opening verse.

Benjamin raps about his own humble beginnings while sneaking into the classroom in a black turban and purple tie-dyed shirt. Visibly bored and irritated, the scene then shifts to Benjamin’s graduation, where he is now in a glowing white cap and gown. The rest of his classmates don dark blue caps and gowns, booing him as he dances across the stage. This scene is significant because it is a visual interpretation of Benjamin’s being booed at the Source Awards: Benjamin’s purple tie-dyed shirt symbolizes the same-colored dashiki he wore at the Source Awards and the video classmates stand in for the New Yorkers who booed him offstage. Benjamin’s white cap and gown represent a physical rendering of his own “graduation” from standardized hip-hop. The classroom scene for Benjamin’s verse is also a visual testament of his verse from “Git Up, Git Out,” the track on which he questions the long-standing southern black mantra of formal education as the (only) path to success.

Waiting outside for Benjamin is Patton in a Cadillac, doubly symbolic of the Cadillac as a literal vehicle of southern upward mobility as well as the mothership/future, waiting to take Benjamin and Patton home. As Patton finishes his verse, he and Benjamin get out of the car and walk toward and into their destiny. A wrecking ball demolishes the car and the video transitions into a dimly lit undisclosed location where Benjamin reads and Patton “preaches” to a group of listeners. They are also seen burning incense and smoking a hookah before the video turns back to the opening scene of the video with Benjamin and Patton leading a group through a jungle. They are on high alert and quickly usher their caravan of followers to keep moving forward as they flee from an unseen evil force. The group makes it to their final destination, a landscape possibly signifying upon the Rastafarian promised land of Zion and a subversion of the biblical Canaan. Children are seen running toward the pyramids as the camera pans to black figures walking around the pyramids and greeting each other. Benjamin and Patton’s eyes glow green in acknowledgment, a physical sign of being an OutKast and alien finally returning home.

The concluding scenes of the “Elevators” music video shows the intersection of multiple threads representing black people’s constant search for home, belonging, and their future selves. It is important to note that in the second half of the video—the journey to home—Benjamin and Patton are parallel to the conductors of the historical Underground Railroad. They are slowly and cautiously moving a group of outcasts through the wilderness to a place of freedom while running from patrollers—akin to slave patrollers—who are hunting them down. The patrollers look for hidden—illegible—signs using infrared vision to make the runaway group’s whereabouts visible. This futuristic tracking method alludes to the past–present futurity of slavery’s long-reaching residual effects tinged with science fiction, particularly the allusions to the Predator film series. With nods toward imagery and the lore of the Underground Railroad and slavery, Rastafarian-influenced imagery of spirituality as a counter to white Christianity, and the pilgrimage of self-discovery, the “Elevators” video presents evidence of OutKast’s use of ATLiens as initial efforts in world-building as a form of legacy that centers on and celebrates the agency of southern black people.

When the Heroes Eventually Die: Aquemini

OutKast’s third album, Aquemini (1998), is a masterful work showcasing the group’s reflection on their legacy as black southerners and their growth as artists. The name, a mash-up of Patton and Benjamin’s astrological signs, carries on the group’s aspirations to be both futuristic and experimental. Aquemini also highlights the group’s maturation as men and as artists in control of their craft. This is most clearly reflected in the album’s production: the group’s own production efforts are more prominent on the album Aquemini with the majority of production credit going to OutKast and their production partner and DJ David “Mr. DJ” Sheats. Aquemini is not OutKast’s first attempt at producing: OutKast and Sheats also produced songs on the ATLi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Mountaintop Ain’t Flat

- 1. The Demo Tape Ain’t Nobody Wanna Hear

- 2. Spelling Out the Work

- 3. Reimagining Slavery in the Hip-Hop Imagination

- 4. Still Ain’t Forgave Myself

- A Final Note: The South Still Got Something to Say

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index