eBook - ePub

Meade at Gettysburg

A Study in Command

- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Although he took command of the Army of the Potomac only three days before the first shots were fired at Gettysburg, Union general George G. Meade guided his forces to victory in the Civil War’s most pivotal battle. Commentators often dismiss Meade when discussing the great leaders of the Civil War. But in this long-anticipated book, Kent Masterson Brown draws on an expansive archive to reappraise Meade’s leadership during the Battle of Gettysburg. Using Meade’s published and unpublished papers alongside diaries, letters, and memoirs of fellow officers and enlisted men, Brown highlights how Meade’s rapid advance of the army to Gettysburg on July 1, his tactical control and coordination of the army in the desperate fighting on July 2, and his determination to hold his positions on July 3 insured victory.

Brown argues that supply deficiencies, brought about by the army’s unexpected need to advance to Gettysburg, were crippling. In spite of that, Meade pursued Lee’s retreating army rapidly, and his decision not to blindly attack Lee’s formidable defenses near Williamsport on July 13 was entirely correct in spite of subsequent harsh criticism. Combining compelling narrative with incisive analysis, this finely rendered work of military history deepens our understanding of the Army of the Potomac as well as the machinations of the Gettysburg Campaign, restoring Meade to his rightful place in the Gettysburg narrative.

Brown argues that supply deficiencies, brought about by the army’s unexpected need to advance to Gettysburg, were crippling. In spite of that, Meade pursued Lee’s retreating army rapidly, and his decision not to blindly attack Lee’s formidable defenses near Williamsport on July 13 was entirely correct in spite of subsequent harsh criticism. Combining compelling narrative with incisive analysis, this finely rendered work of military history deepens our understanding of the Army of the Potomac as well as the machinations of the Gettysburg Campaign, restoring Meade to his rightful place in the Gettysburg narrative.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

HE IS A GENTLEMAN AND AN OLD SOLDIER

Days after the Battle of Chancellorsville, Major General George Gordon Meade, commander of the Fifth Corps of the Army of the Potomac, sat in his tent not far from key fords of the Rappahannock River. There he penned a letter to his wife, Margaretta, whom he called Margaret. He saved his opinions of his fellow generals for his most private correspondence; that day he gave vent to his anger over Major General Joseph Hooker’s disastrous performance. “General Hooker has disappointed all his friends by failing to show his fighting qualities in a pinch,” Meade wrote. “He was more cautious and took to digging quicker than McClellan, thus proving that a man may talk very big when he has no responsibility, but that is quite a different thing, acting when you are responsible [as opposed to] talking when others are.” Two days later, Meade explained to Margaret the fundamental problem brought about by Hooker’s performance: “I think these last operations have shaken the confidence of the army in Hooker’s judgment, particularly among the superior officers.”1

In May 1863, Meade was well known to the army’s professional soldiers, and he was in a good position to assess how his colleagues viewed Hooker’s actions at Chancellorsville. But Meade was not well known in the ranks of the army beyond the Fifth Corps. Reporters did not like mentioning his name in their newspapers. Wrote one of Meade’s staff officers later in the war: “The plain truth about Meade is, first, that he is an abrupt, harsh man, even to his own officers, when in active campaign; and secondly, that he, as a rule, will not even speak to any person connected with the press. They do not dare to address him.”2

Meade was born in Cadiz, Spain, on 31 December 1815, the son of prominent Philadelphians, Richard Worsam Meade, a merchant working in Spain, and Margaret Coats (Butler) Meade. He was the eighth of their eleven children. Forty-seven years old in the spring of 1863, Meade was twenty-eight years out of West Point, where he was graduated nineteenth out of a class of fifty-six in 1835. After graduation, he was assigned as a brevet second lieutenant in the Third United States Artillery to Florida, where he fought the Seminole Indians. On resigning from the army, Meade worked as a civil engineer for a railroad in Alabama. He reentered the army in 1842 as a second lieutenant in the Corps of Topographical Engineers. He served with General Zachary Taylor at Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterrey during the war with Mexico; he also served with General Winfield Scott at Vera Cruz, rising to the rank of captain. After the Mexican War, Meade served assignments constructing lighthouses and improving harbors in New Jersey and Florida; he subsequently oversaw the surveys of Lake Huron and northern Lake Michigan.3

When war broke out in 1861, Meade was commissioned a brigadier general of volunteers in the early fall and placed in command of a brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves in General McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Commanding another brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves was a newly minted brigadier general of volunteers named John Fulton Reynolds, whom Meade trusted and liked, even though he was a professional rival. The two generals fought alongside one another against General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia through the Peninsula Campaign in the spring and summer of 1862. Reynolds was captured during the retreat after the fighting at Gaines’s Mill. Meade was wounded at Glendale; one bullet struck him in the upper right side and then ranged down, exiting out his back just above the hip, while another hit him in the right arm.4

Despite these wounds, Meade returned to command his brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves after about two months of recuperation. Command of the division during Meade’s absence had been given to Reynolds, who had been exchanged, and that division was assigned to the Army of Virginia, commanded by Major General John Pope. Pope’s forces, however, were crushed by Lee’s army along the fields above Bull Run at the end of August. Posting his division across the Warrenton Turnpike near Henry House Hill, Reynolds, with Meade’s brigade, prevented the Confederates from turning their victory into another Union rout.5

When Lee invaded Maryland in September 1862, while at Frederick, Meade was given command of the full division of Pennsylvania Reserves in the First Corps under “Fighting Joe” Hooker. Meade’s sometimes rival Reynolds had been temporarily dispatched to command emergency troops in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Thus when Hooker was wounded at Antietam early on the morning of 17 September, Meade took over command of the First Corps on the battlefield, where he oversaw the incomprehensibly bloody ordeal of fighting in the famed cornfield between the North Woods and the Dunker Church.6

McClellan was finally replaced as commander of the Army of the Potomac for good at Warrenton, Virginia, on 5 November. Two days later, Major General Ambrose Burnside was given command of the army. By then, command of the First Corps had been given to General Reynolds after he returned from Harrisburg, a decision that irritated Meade. After all, Meade already had more combat command experience than Reynolds. “Frankness,” wrote Meade to his wife, “compels me to say, I do wish Reynolds had stayed away, and that I could have had a chance to command a corps in action. Perhaps it may yet occur.” Yet Meade understood that Reynolds possessed a presence that he did not. Reynolds “is very popular and impresses those around him with a great idea of his superiority,” wrote Meade to Margaret Meade, and Reynolds, along with Brigadier General John Gibbon and Major General Abner Doubleday, visited McClellan together on 9 November to bid him farewell. The officers of the old army had a fondness for McClellan, and Meade was among McClellan’s supporters, although he had questioned his lack of aggressiveness.7

Elevated to the rank of major general of volunteers on 29 November, Meade resumed command of the division of Pennsylvania Reserves in the First Corps. As part of Major General William B. Franklin’s “Left Grand Division,” the First Corps and Meade’s division fought well at Fredericksburg on 13 December, though the battle was a disaster for the Union forces. Meade privately admitted to Margaret that he was displeased with Reynolds’s failure to support his attack at Fredericksburg, but it did not seem to compromise an underlying friendship. Nine days later Meade was named commander of the Fifth Corps by Burnside, replacing Major General Daniel Butterfield. By 26 January 1863, Hooker was placed in command of the Army of the Potomac, relieving Burnside. Meade commanded the Fifth Corps during the ensuing Chancellorsville campaign; he had proven to be a capable tactical commander.8

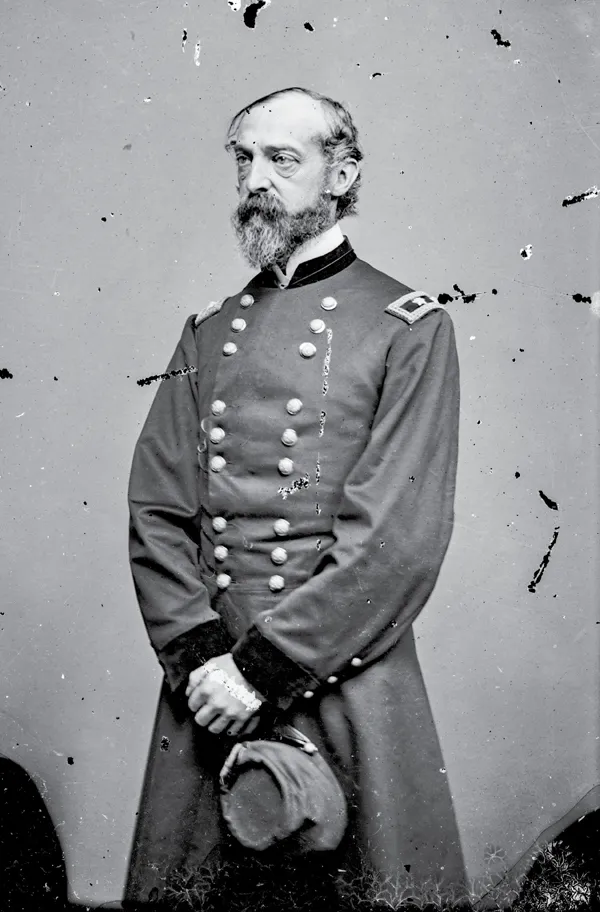

At forty-seven, Meade had the appearance of an older man, tall but rather thin and gaunt. His face was deeply lined; his thinning hair and scraggly whiskers were largely gray. Far-sighted, he used pince-nez spectacles that hung from a lanyard around his neck in order to read. Frederick Law Olmsted, who was then serving in the United States Sanitary Commission, wrote that Meade had a “most soldierly and veteran-like appearance; a grave, stern countenance—somewhat Oriental in its dignified expression, yet American in his race horse gauntness. He is simple, direct, deliberate, and thoughtful in manner and speech and general address. . . . He is a gentleman and an old soldier.”9

Meade’s fellow officers viewed him as sturdy, reliable, competent, and hard-driving; one described him as “clear-headed and honest, [a commander] who would do his best always.”10 Lieutenant Frank A. Haskell, who served on the staff of General John Gibbon, noted that among the officers who knew Meade, “all thought highly of him, a man of great modesty, with none of those qualities which are noisy and assuming, and hankering for cheap newspaper fame. . . . I think my own notions concerning Genl. Meade . . . were shared quite generally by the army. At all events all who knew him shared them.”11

One veteran who knew Meade well described him as “a most accomplished officer.” Meade, he wrote, “had been thoroughly educated in his profession, and had a complete knowledge of both the science and the art of war in all its branches. He was well read, possessed of a vast amount of interesting information, had cultivated his mind as a linguist, and spoke French with fluency.” When foreign dignitaries visited the army, they almost always spent considerable time with Meade.12

Meade did have his detractors, however. He was called a “damned old google-eyed snapping turtle” because he had a tendency to lose his temper and lash out at subordinates. Sometimes officers would find him “in a mood to rake people” or simply “irascible.” He was once described as having “gunpowder in his disposition.” Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Lyman, who would later become one of Meade’s staff officers, recalled that he had an “excellent” temper, which “on occasions burst forth, like a twelve pound spherical case.” When the movement of his troops was on Meade’s mind, Lyman noted, the general was “like a firework, always going bang at someone.” It was said of Meade that “he never took pains to smooth anyone’s ruffled feelings.” Nevertheless, Meade seemed to wear well; the more one served with or under him, the more one grew to respect him.13

Of all the descriptions of Meade, Lyman gives the best glimpse into how he functioned as a commander. Meade, Lyman wrote, “is a thorough soldier, and a mighty clear-headed man; and one who does not move unless he knows where and how many his men are; where and how many his enemy’s men are; and what sort of country he has to go through.” Lyman then added: “I never saw a man in my life who was so characterized by straightforward truthfulness as he is.”14

Apart from his long and loyal service in the army, Meade was a devoted family man. He had been married to the former Margaretta Sergeant, the eldest daughter of Congressman John Sergeant of Pennsylvania, for twenty-two years. Their marriage was consecrated on 31 December 1840, Meade’s birthday. Meade fathered seven children: by the summer of 1863 John Sergeant Meade was twenty-two; George, twenty; Margaret, eighteen; Spencer, thirteen; Sarah, twelve; Henrietta, ten; and William, eight. For all that has been written about Meade over the years, few have noted how much he loved his wife and children. His letters to his family reflect effusive tenderness and devout Christian faith, often reminding Margaret and the children that events are ultimately dictated by the “will of our Heavenly Father.”15

Major General George Gordon Meade. (Library of Congress)

Unlike most of the general officers in the Army of the Potomac, Meade had significant—and rather close—family ties with the Confederacy. His older sister Elizabeth Mary had married a Philadelphian named Alfred Ingraham. The couple moved to Port Gibson, Mississippi, south of Vicksburg, where Alfred managed the banking interests in the Grand Gulf & Port Gibson Railroad Company there of the noted Philadelphian Nicholas Biddle. Elizabeth Mary became an ardent Confederate.16

The Ingrahams lost two sons in the Confederate service. Major Edward Ingraham was mortally wounded near Farmington, Mississippi, on 10 May 1862, while serving on the staff of Major General Earl Van Dorn. He died in Corinth. While at Falmouth, Virginia, in February 1863, Meade received a note under a flag of truce from Edward’s brother, Frank, who informed Meade of Edward’s death and of the death of their sister Apolline’s husband, Thomas LaRoche Ellis, “from exposure in the [Confederate] service.” Ellis had served in Colonel Wert Adams’s First Mississippi Cavalry. Frank’s note ended: “Mother and the rest are all well and wish to be remembered to [their] Yankee relations.” Fighting with the Twenty-First Mississippi in Brigadier General William Barksdale’s Brigade, Frank was killed at Marye’s Heights on 3 May 1863 during the Chancellorsville campaign. Meanwhile, the Ingraham’s plantation at Port Gibson, Ashwood, was overrun and pillaged in early May by Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s forces as they pressed onward to Jackson, Mississippi, and, ultimately, Vicksburg. Major General John A. McClernand coincidentally made the Ingraham’s house his headquarters after the Battle of Port Gibson.17

Another sister of Meade’s, Mariamne, married a Thomas B. Huger of Charleston, South Carolina. She died in 1857, and her husband, a Confederate lieutenant, was killed in action defending Forts Jackson and St. Philip at the mouth of the Mississippi River against Flag Officer David S. Farragut’s Union fleet in April 1862. If that was not enough, Margaret Meade’s younger sister Sarah had married then congressman Henry Alexander Wise of Virginia. Wise had helped secure Meade a commission in the Topographical Engineers at about the time of his marriage to Margaret. The Meades had even named a daughter in honor of Congressman Wise, so close were they. After Sarah’s death in 1850, Wise served as governor of Virginia until the outbreak of the war; in that capacity, he signed John Brown’s death warrant. By the summer of 1863, Wise was a brigadier general in the Confederate service.18

Old Baldy, General Meade’s favorite horse. (Library of Congress)

Although Meade was an unshakable champion of the Union and deeply committed to the old army, he was also devoted to every member of his family. His fervent hope for a reconciliation of the two contending regions on the eve of war unquestionably led him to vote for the moderate John Bell, the Constitutional-Union candidate for president, in the election of 1860. After all, members of his family then had opposing views on the crisis and would undoubtedly choose opposite sides if it came to war.19

Like all general officers, Meade, a fine horseman, had several horses available for his use at all times. He purchased his favorite, Old Baldy, in September 1861. A big, bright bay stallion with a white face and stockings, he had carried Brigadier General David Hunter, who was wounde...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps & Figures

- Prologue

- 1. He Is a Gentleman and an Old Soldier

- 2. As a Soldier, I Obey It

- 3. My Intention Now Is to Move Tomorrow

- 4. I Am Moving at Once against Lee

- 5. You Must Fall Back to Emmitsburg

- 6. Force Him to Show His Hand

- 7. One Corps at Emmitsburg, Two at Gettysburg

- 8. Reynolds Has Been Killed

- 9. Your March Will Be a Forced One

- 10. You Will Probably Have a Depot at Westminster

- 11. Without Tents and Only a Short Supply of Food

- 12. I Wish to God You Could, Sir

- 13. Throw Your Whole Corps at That Point

- 14. Yes, but It Is All Right Now

- 15. I Shall Remain in My Present Position Tomorrow

- 16. Trying to Find a Safe Place

- 17. Our Task Is Not Yet Accomplished

- 18. I Shall Continue My Flank Movement

- 19. I Found He Had Retired in the Night

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Meade at Gettysburg by Kent Masterson Brown, Esq.,Kent Masterson Brown Esq. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.