- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Common views of religion typically focus on the beliefs and meanings derived from revealed scriptures, ideas, and doctrines. David Morgan has led the way in radically broadening that framework to encompass the understanding that religions are fundamentally embodied, material forms of practice. This concise primer shows readers how to study what has come to be termed material religion—the ways religious meaning is enacted in the material world.

Material religion includes the things people wear, eat, sing, touch, look at, create, and avoid. It also encompasses the places where religion and the social realities of everyday life, including gender, class, and race, intersect in physical ways. This interdisciplinary approach brings religious studies into conversation with art history, anthropology, and other fields. In the book, Morgan lays out a range of theories, terms, and concepts and shows how they work together to center materiality in the study of religion. Integrating carefully curated visual evidence, Morgan then applies these ideas and methods to case studies across a variety of religious traditions, modeling step-by-step analysis and emphasizing the importance of historical context. The Thing about Religion will be an essential tool for experts and students alike. Two free, downloadable course syllabi created by the author are available online.

Material religion includes the things people wear, eat, sing, touch, look at, create, and avoid. It also encompasses the places where religion and the social realities of everyday life, including gender, class, and race, intersect in physical ways. This interdisciplinary approach brings religious studies into conversation with art history, anthropology, and other fields. In the book, Morgan lays out a range of theories, terms, and concepts and shows how they work together to center materiality in the study of religion. Integrating carefully curated visual evidence, Morgan then applies these ideas and methods to case studies across a variety of religious traditions, modeling step-by-step analysis and emphasizing the importance of historical context. The Thing about Religion will be an essential tool for experts and students alike. Two free, downloadable course syllabi created by the author are available online.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Thing about Religion by David Morgan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

[ PART I ]

THEORIES AND DEFINITIONS

• • •

[ ONE ]

HOW SOME THEORIES OF RELIGION DEMATERIALIZE IT

• • •

Many approaches to religion do not consider material characteristics to be important. So this chapter is devoted to tracing the history of such theories, indicating how and why they operate as they do, and pointing out the problems with doing so. The point is not to argue that materiality is the essence of all religions or that the material study of a religion is more important than any other. Instead, the task is to demonstrate the difference that studying material aspects of religions makes in understanding them.

Images and Relics as Delusions, Distractions, and Idols: The Priority of Philosophy and Theology

The academic field of religious studies has inherited much from the history of philosophy and theology. That is because philosophy and theology formed the intellectual life of Christianity, and particularly Christian universities in Europe since the eleventh century, long before such modern material disciplines as archaeology, art history, or paleontology came into being. So if we want to understand why some theories of religion give material life little attention, it is necessary to begin with what influential philosophers and theologians have thought about images and objects. Of course, the record is starkly split in the sense that some regarded material things as distractions or even dangers even while the Catholic theology and practice of the Eucharist was robustly material and inspired a rich and varied art and architecture for the devout staging of the rite.1 It is best not to reduce the tradition of Christianity (or any other religion, for that matter) to a single view.

In the twelfth century, the spiritual reformer and mystic Bernard of Clairvaux wrote to William of Saint-Thierry, a friend and admirer who was the abbot of a Benedictine monastery in France, to complain about what he considered the material excess of Benedictine churches: their “vast height, … their immoderate length, their superfluous breadth, the costly polishings, the curious carvings and paintings which attract the worshipper’s gaze and hinder his attention.”2 The decorated capitals of the cloister of the abbey church of Saint-Pierre at Moissac, France, a Benedictine monastery that was rebuilt in the eleventh and twelfth centuries (fig. 8), are just the sort of thing that Bernard had in mind, particularly since they adorned the cloister, or interior courtyard, a part of the monastery that only monks would see.3 Bernard acknowledged that decoration and scale might be done for God’s honor but insisted that bishops had an excuse that monks like Bernard and William did not: “Unable to excite the devotion of carnal folk by spiritual things, [bishops] do so by bodily adornments.” But monks, Bernard claimed, are committed to dismissing “all things fair to see or soothing to hear, sweet to smell, delightful to taste, or pleasant to touch—in a word, all bodily delights.”4 Then Bernard leveled an economic critique of artistic adornment in religious settings: wealth produces more wealth, and the quest for it operated independently of spiritual motives. “Thus, wealth is drawn up by ropes of wealth, thus money bringeth money; for I know not how it is that, wheresoever more abundant wealth is seen, there do men offer more freely.” The problem was the magnetic power of lavish decoration on the spiritually undisciplined nature of the worldly. “Their eyes are feasted with relics cased in gold, and their purse-strings are loosed. They are shown a most comely image of some saint, whom they think all the more saintly that he is the more gaudily painted. Men run to kiss him, and are invited to give; there is more admiration for his comeliness than veneration for his sanctity.”5 And the effect on the spiritual inhabitants of abbeys and cathedral churches was no less a problem—spiritual distraction from the monk’s proper activity: “In short, so many and so marvelous are the varieties of diverse shapes on every hand, that we are tempted to read in the marble than in our books, and to spend the whole day in wondering at these things rather than in meditating on the law of God.”6

FIGURE 8. Detail of carved capitals, cloister of the abbey church of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, France, 12th century. Alinari / Art Resource, NY.

For Bernard, material forms were considered not only to miss the point of religious life but to subvert it by indulging an obsession with material wealth. Decorative and artistic forms are often the target of iconophobic reformers because they are criticized as perverting the spiritual purity of rites and institutions, often because of their association with commerce and the exertions of wealthy patrons. Iconophobia (the fear or avoidance of images) and iconoclasm (the breaking or removal of images) are an attitude and a practice commonly associated with religious reform—and even revolution, since the destruction of images often means an assault on the political and economic orders that installed the images and drew support from their veneration.

In the Byzantine era, for example, a series of emperors banned the use of icons, or religious images, in Orthodox Christian worship during the eighth and ninth centuries. In 754, the iconoclastic emperor Constantine V called a synod or council of bishops to address the matter of images, among other matters. The council indicted “the deceitful colouring of pictures, which draws down the spirit of man from the lofty worship of God to the low and material worship of the creature.”7 Specifically, the Council of Hieria stated that “the sinful art of painting blasphemed the fundamental doctrine of our salvation, namely the Incarnation of Christ.” How was that the case?

What avails, then, the folly of the painter, who from sinful love of gain depicts that which should not be depicted, that is, with his polluted hands he tries to fashion that which should only be believed in the heart and confessed with the mouth? He makes an image and calls it Christ. The name Christ signifies God and man. Consequently, it is an image of God and man, and consequently he has in his foolish mind, in his representation of the created flesh, depicted the Godhead which cannot be represented, and thus mingled what should not be mingled. Thus, he is guilty of a double blasphemy, the one in making an image of the Godhead and the other by mingling the Godhead and manhood. Those fall into the same blasphemy who venerate the image.8

Already in the eighth century we find a contrast between “belief” and “material worship” that is still commonly associated with Protestantism. The distinction is premised on the conviction that any attempt to depict the divine is not only mistaken but a confusion of a human invention with what is invisible and immaterial. With this official finding in place, Constantine V proceeded against the venerators of images, especially directing his efforts at the monasteries, which were producers of icons and communities independent of imperial cities. Monasteries, which were also pilgrimage centers for the display of icons and relics, resisted the imperial ban and struggled for more than a century before they were able to see icon veneration officially reestablished and vindicated as a central feature of Orthodox worship, which it remains to this day.9

The history of iconoclastic reform is not limited to Christianity. In fifteenth- and sixteenth-century China, a reform initiative succeeded at modifying Confucian practice, replacing sculpted images of ancestors in Confucian temple shrines with spirit or ancestor tablets, that is, wooden plaques bearing the names of ancestors. A spirit tablet appears in an important Confucian shrine at Jiading, China, positioned before a statue of Confucius (fig. 9). A fifteenth-century Confucian scholar named Ch’iu Chün argued that the use of sculpted images such as the one that also appears in figure 9 departed from the venerable ancient Confucian tradition. He also claimed that their use was imported from Buddhist practice and therefore not Chinese by nature. And he pointed out that such images often failed on their own terms to visualize ancient Confucian sages because their likenesses were not recorded during their lifetimes, meaning that any image of them was nothing more than the product of an artisan’s imagination.10 The spirit tablets presented only the name and title of the spirit (teacher, sage, ancestor) to which Confucian sacrifice and prayer was directed. The name, uttered in ritual, was regarded as the more adequate means of reference since spirits, according to Ch’iu, bore no features. They were formless, colorless, odorless, and soundless.11 Their presence was to be apprehended only within the context of ritual sacrifice. Thus, even when representations are eliminated, when iconoclasm replaces images with text, a material means of invocation remains. Incense, name plaque, altar, and the sonorous recitation of ritual formula created the stage on which worship took place. Still, Ch’iu focused his iconoclastic arguments on the use of images of sages in the setting of temples in the imperial academies at Beijing and Nanjing. He conceded that he would not remove images from shrines in military districts and “cities of the realm, however, for to change things there would disturb the common people.”12

FIGURE 9. Main hall with spirit tablet displayed before the figure of Confucius, Temple of Confucius, Jiading, China. The temple was built in 1291 and restored in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. © Vanni Archive / Art Resource, NY.

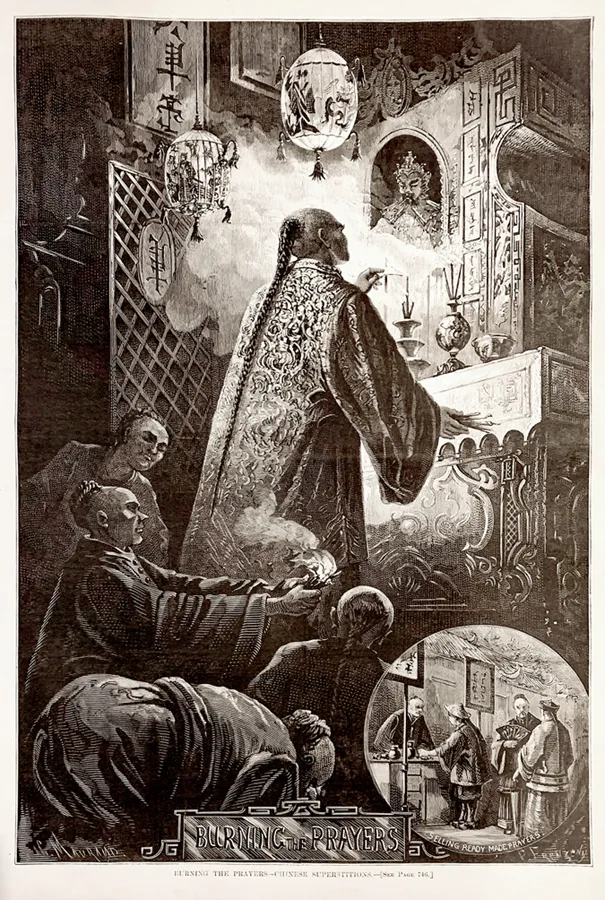

Ch’iu’s critique of cult imagery is not altogether different from the Protestant rejection of imagery in church sanctuaries, an attitude that many Protestant groups developed in the sixteenth century as they split from Roman Catholicism and struggled to establish their reform of religion in the new political circumstances that arose in the German territories, Switzerland, the Netherlands, England, Scotland, and the Scandinavian states farther north.13 North American Protestantism was firmly established during the British colonial era and continued to exert a strong influence on national attitudes into the twentieth century. For instance, as Asian immigration to the United States got seriously under way in the later nineteenth century, many Anglo Protestants expressed alarm and anxiety at the growing numbers of non-Christian Chinese and Japanese, especially in the coastal regions of New York City and San Francisco. Figure 10 registers what amounts to a perennial American concern about immigrants, who alarm some Anglo-Americans because they regard newcomers different from themselves as a threat to their racial and ideological dominance, which they consider to be integral to the divinely mandated mission for the nation, which they view as properly Protestant in origin and identity. Race and religion can be so deeply interwoven as to be inextricable in the imagination of those who consider nation, state, or empire as the political circumstances for realizing divine purpose.

FIGURE 10. G. Mauraud, “Burning the Prayers—Chinese Superstitions,” Harper’s Weekly, August 23, 1873, 745. Photo by author.

Figure 10 certainly conveys this anxiety regarding national identity. It was published in Harper’s Weekly, which regularly printed cartoons intended to stoke alarm about Catholic immigrants from Europe and non-Christian immigrants from Asia as threats to the purity of the nation’s democracy and its foundations in Protestantism. In the illustration, a Chinese priest burns joss-sticks at an altar in San Francisco, before the portrait of a deity or sacred figure, which is surrounded by spirit tablets, while those behind him bow deeply in reverence as their prayers are conveyed to the figure in incense. Entitled “Burning the Prayers—Chinese Superstitions,” the engraving is a piece of Protestant anti-immigrant propaganda aimed at ritual that we have already encountered. In an accompanying text, we read that “the vending of ready-made prayers is a profitable business. They are printed on slips of paper, and a man’s devotion is limited only by the resources of his pocket. Taking the slips home, or into a temple, the devout worshipper lights them in the flame of the lamp or candle, which burns before the image of his deity, and with immense inward satisfaction, if not edification, watches the smoke ascend into the air.”14

Resentment of Chinese immigrant labor often turned on the willingness of Asian laborers to work for less than native Anglo workers, so caricatures of Chinese religion like figure 10 may reflect this economic anxiety. The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed by Congress in 1882 to curb competition from Chinese immigrant labor in the western states, specifically prohibited “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining” from entering the United States for ten years.15 The Harper’s piece may also have intended to reduce Chinese worship to an economic transaction in order to privilege the theology and form of worship practiced by American Protestants. Buying one’s salvation had long been criticized by Protestants as a Catholic and ancient Jewish practice of sacrifice. Asian “idolatry” struck many Protestants as just another version of these imperfect religions, which they considered to misconstrue relations with the divine in terms of a ritual quid pro quo. Moreover, Protestantism was held to be essential to the success of the American republic. In his widely read book Our Country (1885), the prominent Protestant minister Josiah Strong wrote that Anglo-Saxons represented two of the great ideas of civilization: civil liberty and “pure spiritual Christianity.” It was the Saxons of the Reformation, “a Teutonic, rather than a Latin people,” who rose up against “the absolutism of the Pope” to champion religious purity, that is, Protestantism.16 And Strong confidently insisted that North America was “to be the great home of the Anglo-Saxon, the principal seat of his power, the center of his life and influence.”17 This rising white, manly, and English-speaking force in the world was to model the Christian faith that rivaled and would one day triumph over all other religions. Strong approvingly quoted another Protestant writer who coupled religion and race in a scheme of Anglo-Saxon Protestantism that forecasted a global hegemony: “In every corner of the world there is the same phenomenon of the decay of established religions. … Among the Mohammedans, Jews, Buddhists, Brahmins, traditionary creeds are losing their hold.” “Old superstitions,” Strong reiterated, “are loosening their grasp.” The age of Protestant American world dominance was taking shape: “While on this continent God is training the Anglo-Saxon race for its mission, a complemental work has been in progress in the great world beyond.”18

It is important to realize, however, that anxiety about the images of a group other than their own does not mean that Confucians or Protestants (or Jews or Muslims—other groups said to be aniconic, or opposed to images) actually avoided images or cult objects. Protestants used illustrated Bibles and tracts, displayed portraits of their founders and culture heroes, and enthroned Holy Writ in their church sanctuaries, courtrooms, public schools, and parlors. The difference is that “our” images were not idolatrous or sensuous like “theirs.” “Our” images were virtuous, spiritually driven, and acknowledged the true deity and form of worship. And that attitude tended to dematerialize them. Protestantism, in Strong’s words, was a “pure spiritual” religion that set it off against all others, and its racial basis was yet another, related version of purity. Racial thinking was not new in Strong’s day, but it was increasingly elevated to a dominant way of thinking about nations, languages, religions, and cultures. Protestantism was spiritual and immaterial by nature, a purity of race, wil...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: How Materiality Matters to the Study of Religion

- Part I. Theories and Definitions

- Part II. Studying Material Religion

- Conclusion: Things, Networks, and Agents

- Resources for Classroom Use

- Bibliography to Support Student Research

- Notes

- Index

- Back Cover