- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Oil palms are ubiquitous—grown in nearly every tropical country, they supply the world with more edible fat than any other plant and play a role in scores of packaged products, from lipstick and soap to margarine and cookies. And as Jonathan E. Robins shows, sweeping social transformations carried the plant around the planet. First brought to the global stage in the holds of slave ships, palm oil became a quintessential commodity in the Industrial Revolution. Imperialists hungry for cheap fat subjugated Africa’s oil palm landscapes and the people who worked them. In the twentieth century, the World Bank promulgated oil palm agriculture as a panacea to rural development in Southeast Asia and across the tropics. As plantation companies tore into rainforests, evicting farmers in the name of progress, the oil palm continued its rise to dominance, sparking new controversies over trade, land and labor rights, human health, and the environment.

By telling the story of the oil palm across multiple centuries and continents, Robins demonstrates how the fruits of an African palm tree became a key commodity in the story of global capitalism, beginning in the eras of slavery and imperialism, persisting through decolonization, and stretching to the present day.

By telling the story of the oil palm across multiple centuries and continents, Robins demonstrates how the fruits of an African palm tree became a key commodity in the story of global capitalism, beginning in the eras of slavery and imperialism, persisting through decolonization, and stretching to the present day.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oil Palm by Jonathan E. Robins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Oil Palm in Africa

Getting to Know the Oil Palm

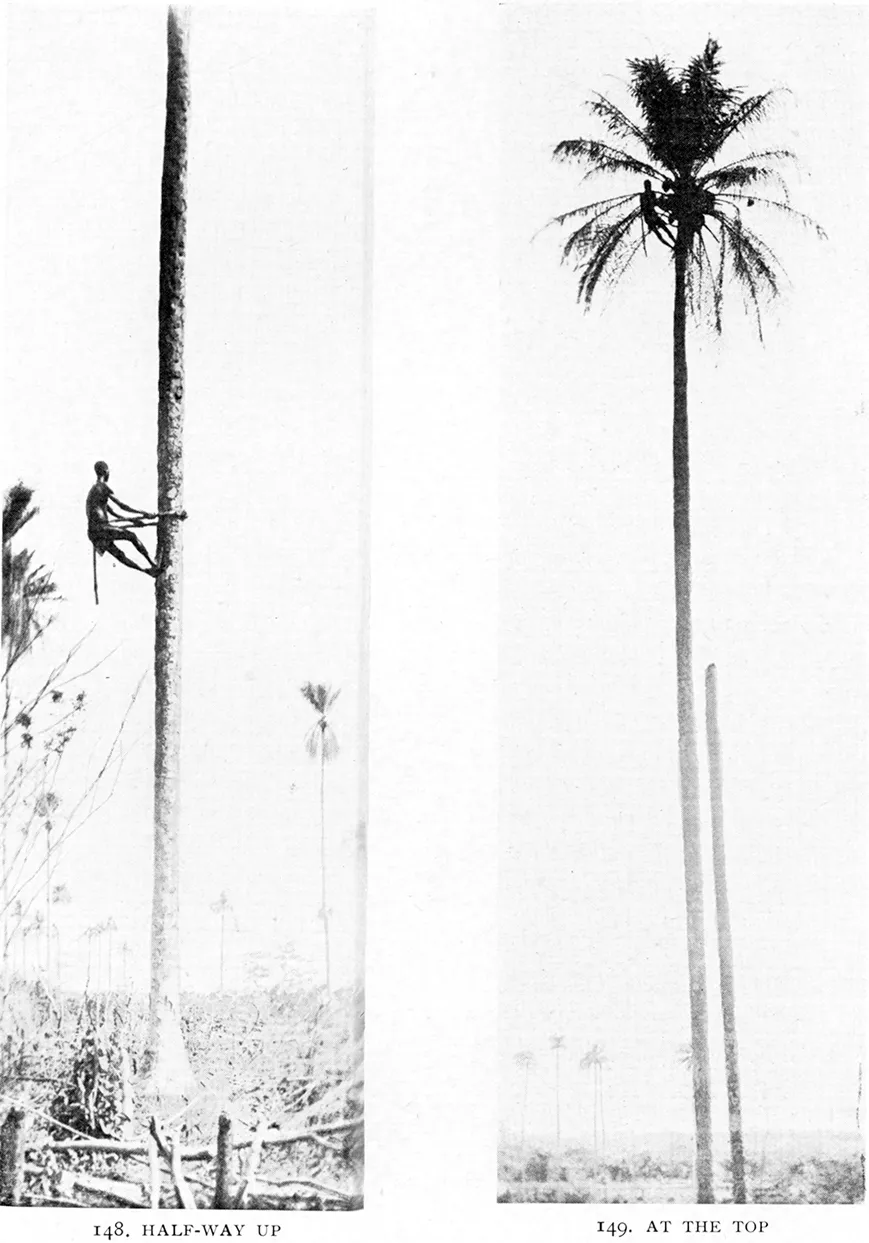

Elaeis guineensis is, as a nineteenth-century writer put it, “one of the most useful inhabitants of the forest, as well as one of its greatest ornaments.”1 A healthy adult specimen can reach thirty meters into the sky, supported by an impossibly slender trunk. Topped with a shock of dark green fronds, it looks like many of its relatives in the palm family, the Arecaceae. Oil palms tower over grassland and “palm bush” scrub in western Africa (figure 1.1); in wetter regions, they form dense groves draped with ferns and orchids. These palms have given Africans an abundant supply of oil for thousands of years. Freshly extracted palm oil is a rich reddish-orange color, free-flowing in tropical heat but thickening in cooler climates. While much depends on how the oil is prepared, palm oil can taste nutty, vegetal, or even smoky, with aromas reminiscent of violets, pumpkins, or carrots.

No other plant supplies as much fat today as the oil palm. Palm oil is usually the cheapest material available for food, soap, and a host of chemical industries. Nearly all of this oil comes from trees in plantations. No longer growing to towering heights, these stubby oil palms stand in neat formations nine meters apart. The long galleries formed by mature trunks and the shady fronds overhead have a pleasing symmetry (figure 1.2). There is a real sense of the sublime in these leafy cathedrals, but it is eerily unlike the tropical forest it replaced.2 There’s little chatter from birds, mammals, or insects, and few splashes of colorful plant life on the plantation.

The beauty of the oil palm fades the closer you get to it. The stems of those green fronds are lined with needle-sharp spines (figure 1.3). The leaflet edges and tips are sharp, too. The palm’s trunk is covered in rough, sharp stubs left by pruning. Most plantation palms succumb to the chainsaw or bulldozer before reaching twenty-five years old, often not long enough for these stubs to drop off. The oil palm’s fruit is rather menacing, too. It grows in hive-like bunches, packed between sharp spikes (figure 1.4). It’s a plant best dealt with at arm’s length. Even so, puncture wounds from spines are a regular occurrence on oil palm plantations.3

FIGURE 1.1 Man climbing a tall oil palm in Liberia using a single-rope technique. The palm stands roughly eighty feet high amid cleared scrub. H. H. Johnston, Liberia, vol. 1, plates 148–49.

People tolerate those spines because, by some evolutionary accident, oil palms produce an incredible amount of fat in their fruit. Unlike fat in a nut, this material doesn’t do much to nourish a seedling. Instead it attracts animals that spread the seeds.4 Most other plants use sugars for this trick. The size of a small plum, palm fruit has firm flesh that is full of stringy fibers. Palm fruit can be black, red, yellow, orange, green, or even white on the outside, depending on the variety and state of ripeness. The flesh inside is typically reddish orange. When this flesh (or pericarp) is smashed, it gives up its oily juice, the source of palm oil. The pericarp surrounds an oil-rich nut, too. Covered in a woody shell, the palm kernel looks like a tiny coconut. When crushed, it yields palm kernel oil, a white-colored fat similar to coconut oil.

In 1763 the Dutch botanist Nikolaus Jacquin dubbed the African oil palm Elaeis guineensis, combining a Greek word for oil with what he presumed was its homeland: Guinea, the western coast of Africa. Jacquin encountered the plant in Martinique, but as any transatlantic traveler could have told him, it was ubiquitous in western Africa. Fossil evidence shows that the oil palm grew in Africa long before it ever appeared in Brazil, which hosts the only significant population of wild oil palms outside Africa.5 The current consensus holds that the African oil palm and its American cousin, Elaeis oleifera, shared an ancestor deep in the past, before Africa and Brazil drifted apart to form the southern Atlantic.6

FIGURE 1.2 Mature oil palms in a Malaysian plantation. Author photo, 2017.

Yet many botanists in the last century puzzled over the fact that oil palms didn’t appear to have a “natural” home in Africa. Foreign writers often insisted that oil palms were forest trees (see chapter 5), but it was clear that oil palms and humans lived together. Wild specimens spring up in forest openings and in wet lowlands, but the tree is not at home in the mature tropical rainforest. In these settings, deciduous giants tower over oil palms, shading them into oblivion. “However tall the palm-tree may be,” a Fante saying tells us, “it stands within the buttress of the silk cotton tree [Ceiba spp.].”7 It may take a century, but palm groves in human-made forest clearings inevitably vanish.8 Oil palms also grow as opportunistic pioneers in drier grassland, but seasonal fires cull most seedlings before their crowns climb high enough to escape damage.

FIGURE 1.3 A cross-section of tenera palm fruit impaled on the sharp spines of a palm frond. The white kernel is visible in the center, surrounded by a thin kernel shell and fibrous, oil-rich flesh. Author photo, 2017.

Today scientists point to swamps or floodplains as the original home of the oil palm. Palms in these environments “look poor, having a thin stem and a small crown and producing small inflorescences.” Their fruit flesh is thin, with thick kernel shells. If the palm came from the swamp, it has moved on to better things with the help of humans.9 Clearly the oil palm emerged somewhere in Africa, and it survived millions of years of change, including the arrival of Homo sapiens. Yet C.W.S. Hartley—the dean of twentieth-century oil palm science—concluded it was “speculative and unrewarding” to think about the oil palm’s distribution in Africa in terms of “wild” palms and “natural” habitats. As far as he was concerned, it was obvious that people were the most important force in the oil palm’s life cycle and had been for centuries.10

FIGURE 1.4 A cluster of ripening tenera palm fruit (“fresh fruit bunch” in industry parlance). Author photo, 2017.

Africans and the Oil Palm

Among the Ngwa Igbo of southeastern Nigeria, one tradition attests, “People came into the world and saw the oil palm.”11 A Guro tradition from Ivory Coast similarly puts oil palms before humans: Bali, the creator, made oil palms ahead of people to sustain Earth’s new inhabitants.12 According to a Bassari source from northern Togo, “there were no other trees but one, a [oil] palm” when God created man (along with an antelope and a snake).13 In Igbo tradition, yams and cocoyams emerged when Chukwu, the creator, ordered Nri to sacrifice his son and daughter. A second sacrifice of a male and a female slave yielded the oil palm and breadfruit tree, respectively. The story links prestigious staples—yams and palm oil—with men, but it puts the oil palm in a decidedly inferior category.14 Whether African traditions gave oil palms precedence over humans or not, they usually regarded the trees as something apart from agriculture and cultivated crops.

MAP 1.1 Oil palm distribution in Africa, with historical areas of dense “emergent” groves indicated. Adapted from Watkins, Palm Oil Diaspora.

Yet palm fruit was more than a wild food gathered to supplement the agricultural diet in antiquity. “Is it a coincidence,” one scientist asked, “that the densest populations in sub-Saharan Africa are in southern Nigeria where the combination of yam cultivation and the exploitation of the oil palm … has been most highly developed?”15 Root crops provide most of the calories people consume across the oil palm’s range (map 1.1), but palm fruit and oil form the base for stews and sauces that make yams and other starches palatable. Palm oil provides critical supplies of vitamin A (which the human body does not produce) and the fat needed to absorb it.16

Archeological materials gathered from Bosumpra Cave in Ghana suggest that humans have been eating palm fruit and kernels for at least 5,000 years.17 Early agriculturalists used fire to clear the landscape but kept oil palms and other useful species.18 They probably didn’t plant oil palms, but rather exploited existing groves and encouraged their spread. A surge in E. guineensis pollen grains found in underwater sediments dating back 3,000 years coincided with the expansion of agricultural settlements across the West African forest zone. Palm kernel shells mixed in with pottery fragments and stone tools in archeological sites attest to the widespread use of oil palms in daily life.19

For many years, scientists argued that Africa’s first agriculturalists hacked and burned their way through a primeval “Guineo-Congolian rainforest” stretching from Sierra Leone to Congo and beyond. In this telling, oil palms were the survivors of forests destroyed by African farmers, leaving “derived savannah” behind.20 New research has overturned that interpretation, however. An “aridification event” about 4,000–5,000 years ago wiped out forests and encouraged the spread of grassland across western Africa. Oil palms probably expanded into these gaps ahead of human settlers, the seeds spread by animals.21

Humans helped the palm along, though, protecting it from grassland fires and voracious elephants.22 Linguistic evidence shows a close link between oil palm dispersion and the arri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures, Graphs, and Maps

- Abbreviations Used in the Text

- Introduction

- 1. The Oil Palm in Africa

- 2. Early Encounters and Exchanges

- 3. From “Legitimate Commerce” to the “Scramble for Africa,”

- 4. Oil Palms and the Industrial Revolution

- 5. Machines in the Palm Groves

- 6. African Smallholders under Colonial Rule

- 7. The Oil Machine in Southeast Asia

- 8. From Colonialism to Development

- 9. Industrial Frontiers

- 10. The Oil Palm’s New Frontiers

- 11. Globalization and the Oil Palm

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index