eBook - ePub

Reconstructing the Landscapes of Slavery

A Visual History of the Plantation in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reconstructing the Landscapes of Slavery

A Visual History of the Plantation in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

About this book

Assessing a unique collection of more than eighty images, this innovative study of visual culture reveals the productive organization of plantation landscapes in the nineteenth-century Atlantic world. These landscapes—from cotton fields in the Lower Mississippi Valley to sugar plantations in western Cuba and coffee plantations in Brazil’s Paraíba Valley—demonstrate how the restructuring of the capitalist world economy led to the formation of new zones of commodity production. By extension, these environments radically transformed slave labor and the role such labor played in the expansion of the global economy.

Artists and mapmakers documented in surprising detail how the physical organization of the landscape itself made possible the increased exploitation of enslaved labor. Reading these images today, one sees how technologies combined with evolving conceptions of plantation management that reduced enslaved workers to black bodies. Planter control of enslaved people’s lives and labor maximized the production of each crop in a calculated system of production. Nature, too, was affected: the massive increase in the scale of production and new systems of cultivation increased the land’s output. Responding to world economic conditions, the replication of slave-based commodity production became integral to the creation of mass markets for cotton, sugar, and coffee, which remain at the center of contemporary life.

Artists and mapmakers documented in surprising detail how the physical organization of the landscape itself made possible the increased exploitation of enslaved labor. Reading these images today, one sees how technologies combined with evolving conceptions of plantation management that reduced enslaved workers to black bodies. Planter control of enslaved people’s lives and labor maximized the production of each crop in a calculated system of production. Nature, too, was affected: the massive increase in the scale of production and new systems of cultivation increased the land’s output. Responding to world economic conditions, the replication of slave-based commodity production became integral to the creation of mass markets for cotton, sugar, and coffee, which remain at the center of contemporary life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reconstructing the Landscapes of Slavery by Dale W. Tomich,Reinaldo Funes Monzote,Carlos Venegas Fornias,Rafael de Bivar Marquese in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Lateinamerikanische & karibische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Making Landscapes

NEW ATLANTIC COMMODITY FRONTIERS

During the nineteenth century, cotton, sugar, and coffee became commonplace items of everyday consumption for larger and larger segments of the world’s population. Industrialization, urbanization, and population growth all contributed to the dramatically increased demand for these products. Cotton, the raw material of the Industrial Revolution, became the leading item in international trade, followed closely by sugar and coffee. Supplying the growing demand for these crops entailed the creation of new productive spaces1 and the reconstitution of slavery and redeployment of slave labor.2 In the U.S. South, Cuba, and Brazil, extensive tracts of unexploited land were adapted to the new conditions for the mass production of these crops. The lower Mississippi valley, the broad prairie (llanura) of western Cuba, and Brazil’s Paraíba Valley emerged as new zones of plantation production on the basis of slave labor. The creation of these zones—the fateful combination of plantation monoculture, mass slavery, and the reordering and transformation of environments—was not simply the result of choices made by local or regional elites. Rather, these zones were the outcome of the complex interaction of world-economic and local relations and processes. Each represents a distinct response to the forces restructuring the nineteenth-century world-economy.

Each of these new zones of slave plantation production formed a distinct “commodity frontier” that offered extremely favorable environmental and geographic conditions for large-scale production of its particular crop3—cotton in the lower Mississippi valley, sugar in Cuba, and coffee in the Paraíba Valley. The formation of slave plantation complexes in these new zones was driven by the availability of virtually unlimited tracts of land and the mobility of enslaved labor. Specific ecologies combined with growing world demand to create specialization among the three frontiers. Each zone concentrated on the most appropriate crop for its particular conditions. In each zone, environmental, spatial, and social relations were dramatically restructured and transformed. In each, indigenous populations had been eliminated in one way or another, and there were no groups who could oppose the unrestrained expansion of the plantation system. In each, subordination to the dominant crop reordered and simplified biologically complex ecologies with devastating environmental consequences. In each, concrete, substantive historical slave relations were constituted not only by the form of master-slave relations but also by the material conditions and processes required for the production of each particular crop and additionally by their relative position in the world division of labor and world market. Thus, each slave formation forms a particular historical-geographic complex4 within the historically changing world division of labor. In each zone, the slave labor process and master-slave relations assumed distinct social and material characteristics that differentiated them from other such slave formations. The formation of these zones expanded the scale of production beyond that of older zones producing the same commodities. These new zones were characterized by more extensive areas under cultivation, more and larger plantations, and greater economies of scale that lowered the costs of production by producing greater volumes of the crop.5

We may distinguish a temporal and spatial sequence in the development of commodity frontiers. First was a pioneering phase: abundant land was available, and virgin soils were highly fertile. The labor force was built up, and much of its energy was engaged in clearing the forest, draining the land, constructing buildings and roads, and creating the infrastructure for large-scale commercial agriculture. The pioneer phase was followed by a phase of maturity. The land and labor force were at their peak efficiency, and the crop yield was high. The output of the plantation was at its highest. This phase was followed by a phase of decadence. Soil fertility and plant yield declined, and the slave labor force matured. There were fewer prime workers in the slave population. The gender ratio was more equal between men and women, and there were more children and elderly. These temporal phases coexisted in space and translated into three distinct zones in any commodity frontier.6

The formation of these new historical-geographic complexes depended upon the deployment of transportation systems that were capable of cheaply and efficiently carrying massive quantities of bulky commodities across long distances. New technologies of production and transport integrated each zone into transnational commodity circuits. Each such system—including the railroad, the steamboat, and, in Brazil, the remarkable system of mule transport—adapted to specific local geographies, the material attributes of the crop, and the requirements of large-scale commodity circulation and consumption. These extended commodity frontiers meant that the sites of production were located farther from the centers of processing and consumption. Goods had to be transported over longer distances, and carriers were under pressure to increase capacity and lower costs. Thus, longer lines of communication themselves encouraged further increases in the scale of production in order to guarantee full cargoes and maintain profits for carriers. At the same time, the interdependence of increasing scale and cheaper unit costs in production and transport stimulated consumption. These general conditions intersected with distinct local environments and geographies to create specific social and economic histories in each zone.7

Because these new frontier zones were sparsely settled, they lacked an adequate labor supply to meet the requirements of the new crops. In each of them, the scale of slave production was dramatically increased in order to satisfy growing world demand for cotton, sugar, and coffee. The forced migration of chattel slaves supplied the demand for labor in each zone and shaped its respective plantation system. Despite abolitionist and British pressure to end the international slave trade, more than 2,400,000 Africans were transported from Africa to the Americas between 1801 and 1866, perhaps the highest level of activity for any comparable period in the history of the Atlantic slave trade.8 More than 1,500,000 captives arrived in Brazil during this period and over 640,000 in Cuba. Of these, the overwhelming majority were destined for the Brazilian coffee zone and the Cuban sugar zone. In the United States, more than 1,000,000 slaves were taken from the Upper South to the cotton frontiers of the Deep South,9 while in Brazil over 200,000 slaves were transferred to the new coffee frontiers of the Paraíba Valley and São Paulo after 1850.10 At the very moment when modern industry, free trade, and the increasing strength of political liberalism and abolitionism are generally thought to have led to the end of the slave trade and the abolition of chattel slavery, more slaves were being transported across the Atlantic world and were producing more commodities on more land than ever before in the 400-year history of slavery.

In these far-flung commodity frontiers, slavery itself was remade in ways that conformed to the requirements of industrial production, capitalist world markets, and a postcolonial Atlantic political order. The particular material conditions required for the cultivation and processing of each crop structured the organization of the plantation and slave labor. Accelerating world demand for cotton, sugar, and coffee not only increased the number and size of plantations and restructured the organization of productive space but also concentrated more slaves, reconfigured labor processes, and intensified their labor in these new commodity frontiers. This new “second slavery” was characterized by increased output per slave, the incorporation of new production and transport technologies, and new strategies of land and labor management based upon new conceptions of time and space, quantification, measurement, and calculation.11

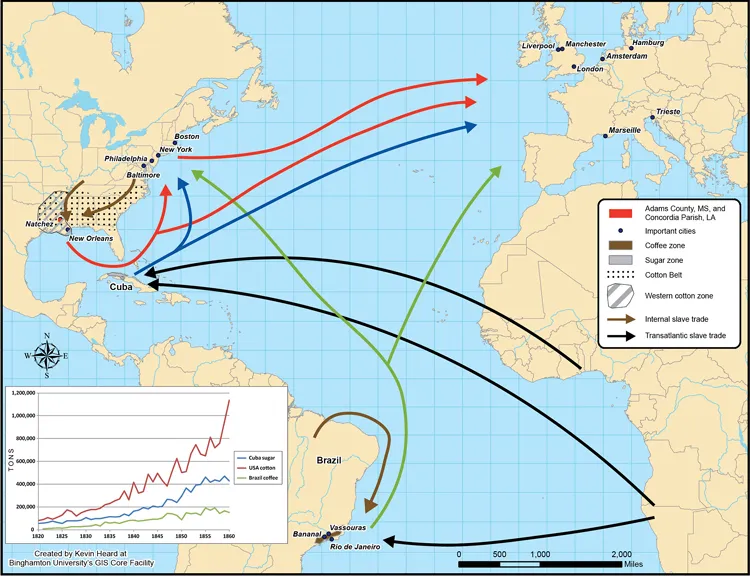

These previously marginal geographic zones emerged as key poles of the new world division of labor as each achieved unprecedented levels of production and rates of expansion. The U.S. South, western Cuba, and the center-south of Brazil each became the world’s leading producer of its respective crop and anchored new commodity circuits that reconfigured the international division of labor. In place of the classic triangle trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas as the basic structure of Atlantic commerce, the United States became the world’s primary producer of cotton, supplying between 70 and 80 percent of the raw material for Britain’s Industrial Revolution, and at the same time it emerged as the major consumer of Cuban sugar and Brazilian coffee. After 1815 the Atlantic slave trade reached perhaps its highest level, but Cuba and Brazil were virtually its exclusive destinations (see map PI.1). As production expanded in each zone and the volume of commodities in circulation reached unprecedented levels, each zone became more closely integrated into broader global networks of exchange, distribution, and consumption. The growing availability of cotton, sugar, and coffee shaped new patterns of consumption that contributed to a distinctively modern way of life.

Map PI.1. New Atlantic commodity frontiers, 1815–1868. Created by Kevin Heard, Binghamton University, GIS Core Facility.

The interaction of these various forces and relations reshaped the land and created distinctive working plantation landscapes in each of these new commodity frontiers. Each zone represents a distinct local response to the same world-economic conditions. In each there was an enormous increase in the scale of production. Land and labor were organized to maximize production and productivity. Monocultural agriculture expanded extensively and intensively. Plantation slaves were subject to more exacting rationalization of their working activity and more rigid hierarchy, racialization, and regimentation of their social lives. Production was more effectively integrated into the world market. Land and labor were subject to increasing rates of exploitation. Spatial ordering facilitated production and social control. However, in each zone the particular characteristics of each crop, the environment, topography, hydrology, the soil fertility, the available sources of power and means of transportation, and strategies of crop and labor management shaped particular configurations of landscape and formed singular spatial economies.12 At the same time, the landscape and built environment embodied social and racial inequalities and expressed a symbolic order that sought to construct social meanings and legitimate authority. Thus, each landscape physically objectified these diverse material and physical conditions, social relations and processes, and expressed culturally formed symbolic meanings through which they were interpreted.13 Nature, labor, power, and culture wove through plantation spaces and endowed them with specific identities and forms, even as the institution of the plantation unified the history of the Americas.

1

The Lower Mississippi Valley Cotton Frontier

The mechanization of the textile industry in Britain created growing world demand for cotton. The world cotton market expanded dramatically and continuously throughout the first part of the nineteenth century as this industrial raw material became the leading product in international trade.1 The U.S. South soon emerged as the world’s primary supplier of raw cotton. With the invention of the cotton gin, cotton spread rapidly across the South and revitalized slavery. At its height, the Cotton Belt stretched from the Carolinas to Texas. From the end of the War of 1812 to the beginning of the Civil War in 1860, U.S. cotton production climbed from fewer than 150,000 bales to over 4,500,000 bales. Even as world production increased sharply during the period between 1840 and 1860, the United States annually produced over 60 percent of the world supply and accounted for over 50 percent of U.S. exports by value. Between 85 percent and 90 percent of the U.S. crop was exported to Britain and accounted for nearly 80 percent of British cotton imports during the period before the Civil War. The slave plantations of the cotton South were tightly bound to the textile mills of Manchester.2

The growing world demand for cotton reshaped the physical geography of the South, subordinating it to the material conditions of cotton production and the socioeconomic characteristics of slave labor. Cotton requires no complex processing and can be adapted to different kinds of agriculture. It can be grown as a supplementary crop for small subsistence farmers, on small farms specializing in cotton, or on large-scale plantations as a monocultural crop. Each of these kinds of agricultural organization was found in the South as the lure of the cotton market and the promise of wealth attracted a variety of cultivators to the crop. Nonetheless, the cotton crop was dominated by the largest plantations with the most slaves. These plantations were concentrated in fertile river valleys, which offered both rich soils and access to world markets.3 This combination of fertile soils and cheap water transportation had been key to development of southern tidewater plantation agriculture since colonial times. The Cotton Belt continued this pattern. From Georgia to Louisiana and Texas, access to cheap river transportation to the Gulf of Mexico made possible the development of extensive zones of cultivation dominated by large plantations. The acquisition of West Florida from Spain was a crucial development of the Cotton South because it provided a river outlet to the Gulf for the huge quantities of cotton produced in Georgia, Florida, and Alabama. The Apalachicola, Mobile, and (above all) Mississippi Rivers were vital arteries for the Cotton South, and the ports of Apalachicola, Mobile, and New Orleans became centers of the cotton trade. Without these transportation linkages, the development of the Cotton Belt would not have been possible.

The Natchez District along the Mississippi River quickly emerged as perhaps the most productive center of cotton cultivation in the South during the first half of the nineteenth century. The district included Wilkinson, Adams, Jefferson, Claiborne, and Warren Counties in Mississippi and Concordia, Tensas, and Madison Parishes in Louisiana. Its humid, subtropical climate with warm temperatures, abundant rainfall, long summers, and short, mild winters offered exceptional conditions for cotton cultivation. However, the lower Mississippi valley cotton frontier reached far beyond the Natchez District. The city of Natchez, in Adams County, Mississippi, was the hub of a cotton-producing hinterland extending from Mississippi and Louisiana to Arkansas and Texas. Natchez’s strategic position on the Mississippi River, abundance of fertile la...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Map, Table, and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. Cotton, Sugar, Coffee, and the Making of Nineteenth-Century Slave Plantations

- Part I. Making Landscapes: New Atlantic Commodity Frontiers

- Part II. Spatial Economies and Plantation Landscapes

- Conclusion. Geometries of Exploitation

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Back Cover