- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Study Companion is a valuable additional resource for introductory courses in world religions that use Christopher Partridge's Introduction to World Religions, Second Edition. Thoroughly checked and updated to work flawlessly with the revised second edition of this important text, the Study Companion provides biographical information, primary source readings, bibliographies, and many other pedagogical tools to enhance the student's experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Study Companion to Introduction to World Religions by Beth Wright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Part 1: Understanding Religion

Chapter Summaries

1. What Is Religion?

Scholars in the past and today have focused on the personal expression of faith and the organized institution as two major aspects of religion apparent across cultures. Essentialists define the essence of religion (faith, belief) as nonempirical and focus on the outward behavior reflected by that essence. Functionalists study religion’s societal roles through a variety of lenses, including psychology, sociology, and politics. A third approach looks at the wide variety of religions as part of a family whose members share certain traits.

2. Phenomenology and the Study of Religion

Phenomenology is one historical approach to the study of religion, involving a classification of the various aspects of religion, including objects, rituals, and teachings. Some scholars go a step further and define religions by their a priori sense of the holy. This philosophical approach raises the question of objectivity in the study of religion; one must ask how an outsider (a nonbeliever) can understand a religion in the way an insider, or believer, does. A common approach in contemporary scholarship is to acknowledge the inherent cultural biases of the person studying a religion and to use rigorous, critical analysis, or metatheory, to engage with and critique the scholar’s own assumptions.

3. The Anthropology of Religion

An anthropological approach to religion focuses on the cultural aspects. Emile Durkheim’s view that religion is a projection of society’s values and Mary Douglas’s studies of symbols and classifications have been influential in the field. Myths and symbols offer another doorway to understanding religion; while myths highlight significant issues and values of a given culture, symbols help believers find personal meaning within a religious tradition.

4. The Sociology of Religion

Contemporary sociological study of religion focuses on the social construction of religion and, in particular, the connections between beliefs and practices. Max Weber, a major influence on the field, established what is now called “meaning theory,” which emphasizes the way religion gives meaning to human life and society. More recent areas of study within the field are secularization and new religious movements.

5. The Psychology of Religion

William James attempted to promote a scientific view of religion, while Sigmund Freud considered religious belief to be based on an illusion. Carl Jung had a more positive approach than Freud in his psychological studies, focusing on the role the image of God plays in the psyche as part of an individual’s development. Contemporary scholarship has developed in a number of areas, including children’s religious development, connections between mental health and religious belief, and the study of charismatic religion.

6. Theological Approaches to the Study of Religion

A theological study of a religion seeks to understand what it means to its believers and how it functions as a worldview. Some scholars may focus on an emic or etic approach—a believer’s viewpoint or an external observer’s. Other scholars subscribe to the insider/outsider concept in which they are always outsiders studying the insiders, or believers. The question of objectivity is always in play, so that a theological approach must acknowledge the observer’s cultural biases whether from inside or outside the religious tradition. Comparative religious study has offered insights into how religions influence each other and therefore the scholarship developed about them.

7. Critical Theory and Religion

Critical theory about religion developed in Western thought as part of a general trend that questioned notions of truth and certainty of knowledge. The most influential thinkers in this area are Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Sigmund Freud. While the Frankfurt School followed Marx and Freud in seeing religion and culture as being manipulated by those in power, post-structuralists like Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida focused on the historical nature of ideas and the instability of language that lead to questioning all assertions about knowledge.

8. Ritual and Performance

Depending on a scholar’s methodology, rituals may be analyzed for their specific roles within a religious tradition or their value within a given culture. Catherine Bell has created categories of rituals based on what they do, like serving as rites of passage or commemorating an event. Mircea Eliade discussed ritual as reenacting myth, bringing the past into the present. Arnold van Gennep noted the underlying pattern beneath rituals of separation, transition, and reintegration. Bruce Lincoln has studied female initiation and points to the different pattern involved: enclosure, metamorphosis or magnification, and emergence.

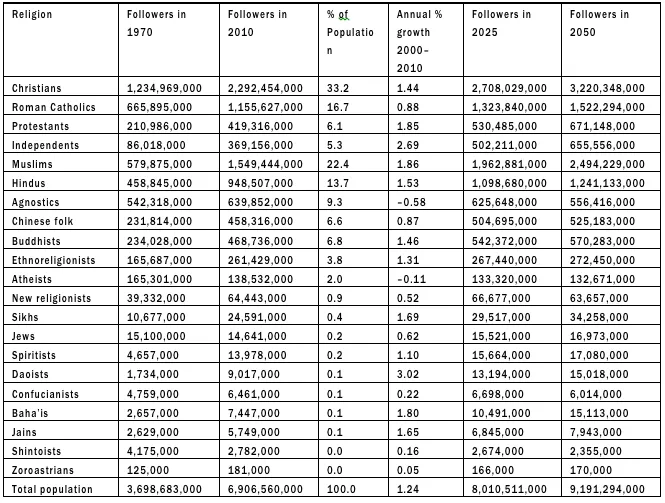

Religious Adherents of Major Traditions in the World

Source: J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, eds., Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd ed. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010), lix

Key Personalities

Karl Marx (1818–83)

German intellectual who critiqued capitalism and the function of religion in society.

“The philosopher, social scientist, historian and revolutionary, Karl Marx, is without a doubt the most influential socialist thinker to emerge in the 19th century. Although he was largely ignored by scholars in his own lifetime, his social, economic and political ideas gained rapid acceptance in the socialist movement after his death in 1883.” (Steven Kreis, “Karl Marx, 1818-1883,” 2000, The History Guide: Lectures on Modern European Intellectual History, http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/marx.html)

“Marx published A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy in 1859. . . . Marx argued that the superstructure of law, politics, religion, art and philosophy was determined by economic forces. ‘It is not,’ he wrote, ‘the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.’ This is what Friedrich Engels later called ‘false consciousness.’ ” (John Simkin, “Karl Marx: Biography,” Spartacus Educational, n.d., http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/TUmarx.htm)

Additional Resources

Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1 (English translation of Das Kapital) http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/

Text of The Communist Manifesto (downloadable text file) http://www.indepthinfo.com/communist-manifesto/text.shtml

Émile Durkheim (1858–1917)

French scholar considered the father of sociology.

“[Since his] grandfather and great-grandfather had also been rabbis, [he] appeared destined for the rabbinate, and a part of his early education was spent in a rabbinical school. This early ambition was dismissed while he was still a schoolboy, and soon after his arrival in Paris, Durkheim would break with Judaism altogether. But he always remained the product of close-knit, orthodox Jewish family, as well as that long-established Jewish community of Alsace-Lorraine that had been occupied by Prussian troops in 1870, and suffered the consequent anti-Semitism of the French citizenry. Later, Durkheim would argue that the hostility of Christianity toward Judaism had created an unusual sense of solidarity among the Jews.” (Robert Alun Jones, Emile Durkheim: An Introduction to Four Major Works [Beverly Hills: Sage, 1986], http://durkheim.uchicago.edu/Biography.html)

“In 1912, Durkheim published his fourth major work, Les Formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse (The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life). . . . His scientific approach to every social phenomenon had not only managed to draw the ire of the Catholic Church, some philosophers, and the Right Wing, but he had also gained quite a fair bit of power in the world of academia; his lecture courses were required curriculum for all philosophy, literature, and history students.” (“Emile Durkheim Biography,” 2002, http://www.emile-durkheim.com/emile_durkheim_bio_002.htm)

Additional Resources

The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1915 edition available for online viewing or in downloadable forms) http://www.archive.org/details/elementaryformso00durk

The Rules of Sociological Method and Selected Texts on Sociology and Its Method (portions of text available on Google Books)http://books.google.com/books?id=dM01B9O6s8YC

Mircea Eliade (1907–86)

A Romanian-born philosopher and historian of religion who served thirty years as chair of the history of religions department at the University of Chicago.

“Eliade contends that the perception of time as an homogenous, linear, and unrepeatable medium is a peculiarity of modern and non-religious humanity. Archaic or religious humanity (homo religiosus), in comparison, perceives time as heterogeneous; that is, as divided between profane time (linear), and sacred time (cyclical and reactualizable). By means of myths and rituals which give access to this sacred time religious humanity protects itself against the ‘terror of history,’ a condition of helplessness before the absolute data of historical time, a form of existential anxiety.” (Bryan Rennie, “Mircea Eliade (1907-1986),” n.d., http://www.westminster.edu/staff/brennie/eliade/mebio.htm)

“Eliade started to write The Myth of the Eternal Return in 1945, in the aftermath of World War II, when Europe was in ruins, and Communism was conquering Eastern European countries. The essay dealt with mankind’s experience of history and time, especially the conceptions of being and reality. According to Eliade, in modern times people have lost their contact with natural cycles, known in traditional societies. Eliade saw that for human beings their inner, unhistorical world, and its meanings, were crucial. Behind historical processes are archaic symbols. Belief in a linear progress of history is typical for the Christian worldview, which counters the tyranny of history with the idea of God, but in the archaic world of archetypes and repetition the tyranny of history is accepted. . . . Eliade contrasts the Western linear view of time with the Eastern cyclical world view.” (Petri Liukkonen and Ari Pesonen, “Mircea Eliade (1908-1986),” 2008, http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/eliade.htm)

Additional Resources

The Sacred and the Profane (the text of the book viewable online and in downloadable form) http://www.scribd.com/doc/312238/Mircea-Eliade-The-Sacred-The-Profane

“Mircea Eliade” (an essay exploring the nature of Eliade’s association with Heidegger and right-wing politics during the Nazi era and how it affected his philosophy of religion)http://www.friesian.com/eliade.htm

Emmanuel Levinas (1906–95)

Lithuanian-born philosopher, ethicist, and Talmudic commentator who influenced postmodern thinkers such as Derrida.

“Levinas’ philosophy is directly related to his experiences during World War II. His family died in the Holocaust, and, as a French citizen and soldier, Levinas himself became a prisoner of war in Germany. . . . This experience, coupled with Heidegger’s affiliation to National Socialism during the war, clearly and understandably led to a profound crisis in Levinas’ enthusiasm for Heidegger. . . . At the same time, Levinas felt that Heidegger could not simply be forgotten, but must be gotten beyond. If Heidegger is concerned with Being, Levinas is concerned with ethics, and ethics, for Levinas, is beyond being—Otherwise than Being.” (Bren Dean Robbins, “Emmanuel Levinas,” Mythos & Logos, 2000, http://mythosandlogos.com/Levinas.html)

“Levinas’s second magnum opus, Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence (1974), an immensely challenging and sophisticated work that seeks to push philosophical intelligibility to the limit in an effort to lessen the inevitable concessions made to ontology and the tradition . . . is generally considered Levinas’s most important contribution to the contemporary debate surrounding the closure of metaphysical discourse, much commented upon by Jacques Derrida, for example.” (Peter Atterton, “The Emmanuel Levinas Web Page,” n.d., http://www.levinas.sdsu.edu/)

Additional Resources

“Emmanuel Levinas,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (essay discussing Levinas’s philosophy; includes biographical outline) http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/levinas/

Basic Philosophical Writings (portions of text available on Google Books) http://books.google.com/books?id=dmHH1Xie8Q0C

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009)

French scholar who pioneered structural anthropology.

“The basis of the structural anthropology of Lévi-Strauss is the idea that the human brain systematically processes organised, that is to say structured, units of information that combine and recombine to create models that sometimes explain the world we live in, sometimes suggest imaginary alternatives, and sometimes give tools with which to operate in it. The task of the anthropologist, for Lévi-Strauss, is not to account for why a culture takes a particular form, but to understand and illustrate the principles of organisation that underlie the onward process of transformation that occurs as carriers of the culture solve problems that are either practical or purely intellectual.”(Maurice Bloch, “Claude Lévi-Strauss Obituary,” Guardian [London], November 3, 2009, http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2009/nov/03/claude-levi-strauss-obituary)

“ ‘Mythologiques,’ his four-volume work about the structure of native mythology in the Americas, attempts nothing less than an interpretation of the world of culture and custom, shaped by analysis of several hundred myths of little-known tribes and traditions. . . . In his analysis of myth and culture, Mr. Lévi-Strauss might contrast imagery of monkeys and jaguars; consider the differences in meaning of roasted and boiled food (cannibals, he suggested, tended to boil their friends and roast their enemies); and establish connections between weird mythological tales and ornate laws of marriage and kinship.”(Edward Rothstein, “Claude Lévi-Strauss, 100, Dies; Altered Western Views of the ‘Primitive,’ ” New York Times, November 4, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/04/world/europe/04levistrauss.html)

Additional Resources

“Library Man: On Claude Lévi-Strauss” (an in-depth review of Patrick Wilcken’s biography of Lévi-Strauss)http://www.thenation.com/article/157879 /library-man-claude-levi-strauss

The Raw and the Cooked (vol. 1 of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table Of Contents

- For the Instructor

- For the Student

- Part 1: Understanding Religion

- Part 2: Religions of Antiquity

- Part 3: Indigenous Religious

- Part 4: Hinduism

- Part 5: Buddhism

- Part 6: Jainism

- Part 7: Chinese Religions

- Part 8: Korean and Japanese Religions

- Part 9: Judaism

- Part 10: Christianity

- Part 11: Islam

- Part 12: Sikhism

- Part 13: Religions in Today's World

- A Short Guide to Writing Research Papers on World Religions