- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Paul: Apostle to the Nations by Walter F. Taylor Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Criticism & Interpretation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

3

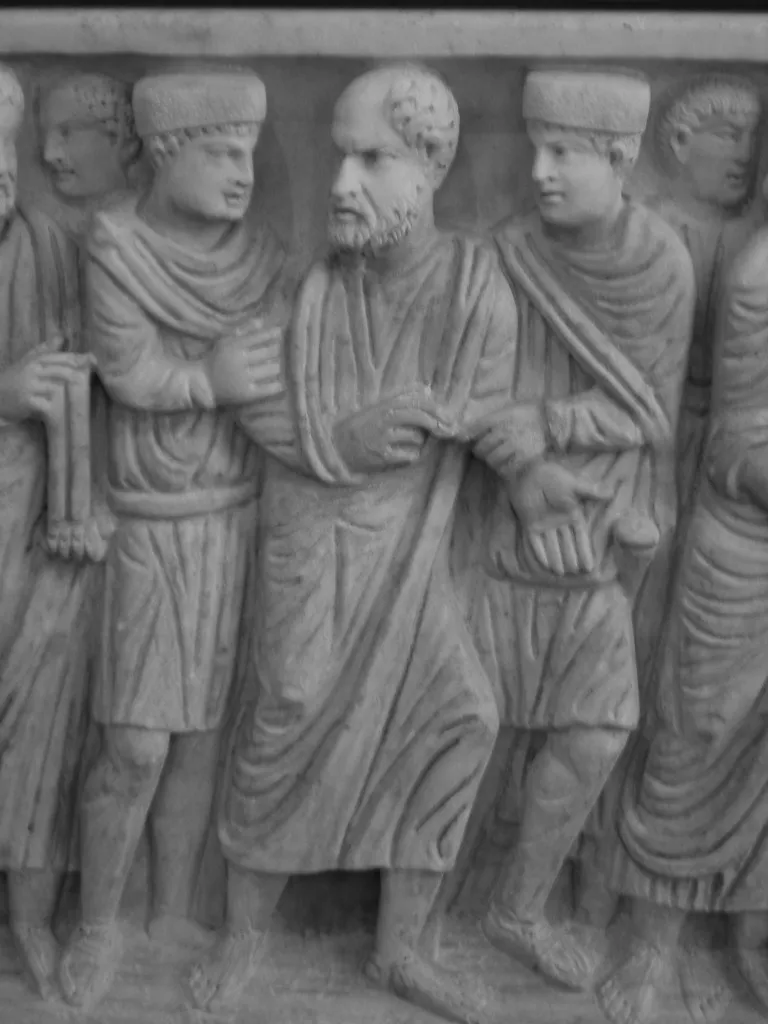

Fig. P1.1. Paul under arrest, from a Roman sarcophagus (third century). Palazzo Massimo, Rome. Photo: Neil Elliott.

Fig. P1.2. The Apostle Paul, by Domenikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco, sixteenth century). Original in the Casa y Museo del Greco, Toledo, Spain.

Fig. P1.3. The Apostle Paul, by Anton Rublev (ca. 1410). Original in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

4

Introduction: Why Study Paul?

Introduction

Why Study Paul?

Fig. Int. 1. Early third-century fresco of the apostle Paul, from the catacomb of St. Domitilla, Rome.

Positive and Negative Evaluations of Paul

Think of a well-known but controversial public figure from the present or the past: Barack Obama, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Lady Gaga, Eleanor Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan. Each person has passionate supporters—and equally ardent opponents. Paul, an early Christ-believing missionary, apostle (or “messenger,” see chapter 3), theologian, and author, has elicited the same kind of sharply opposed reactions. Over the centuries, he has been appreciated as the most important apostle and vilified as virtually the Antichrist.

For Christian thinkers like Augustine (354–430) and Martin Luther (1483–1546), Paul and his thought are at the very heart of the Christian theological enterprise. Thus, Luther wrote that Paul’s letter to believers in Rome “is in truth the most important document in the New Testament, the gospel in its purest expression. . . . It is the soul’s daily bread, and can never be read too often, or studied too much. . . . It is a brilliant light, almost enough to illumine the whole Bible.”[1] John Wesley (1703–1791), the founder of Methodism, at a crucial point in his development felt his “heart strangely warmed” when he heard Luther’s words about Paul read. Throughout his career, Wesley repeatedly returned to Romans in his sermons and writings. In the twentieth century, Karl Barth (1886–1968) and Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) acknowledged the importance of Paul for ongoing Christian witness. For such thinkers, Paul’s radical analysis of human nature and sin, coupled with his profound emphasis on God’s unmerited love given to humanity in the cross of Jesus, provided clear answers to questions about the meaning of life in general and the God-human relationship in particular.

For others, however, the view of Paul has been quite different. In his own lifetime, Paul not only was opposed by Judeans who did not believe in Jesus—which might seem natural—but also was fiercely opposed by other Christ-believing missionaries (see the chapters on Galatians, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, and Philippians). After his death, some ancient Judean-Christ-believing communities denounced him as the “enemy” or the “messenger of Satan,” apparently because he relaxed the requirements of the Law of Moses (see chapter 13 on “The Apostate Paul”). In the nineteenth century, many scholars saw Paul as the corruptor of the simple ethical system of Jesus. For Paul de Lagarde, for instance, Paul was the one who burdened Christianity with Israel’s Bible.[2] Even thinkers with no claims to being biblical scholars have had their opinions about Paul. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote of Paul as the “dys-evangelist,” that is, the negative evangelist, the proclaimer of bad news. The playwright George Bernard Shaw wrote in 1913 a section on “The Monstrous Imposition upon Jesus” as part of his preface to Androcles and the Lion. The “monstrous imposition” is Paul’s theology.[3]

For opponents of slavery in the American South, Paul seemed a fickle resource: in tandem with ringing endorsements of freedom and equality (Gal 3:28; 5:1) went his positive use of the slave image (Rom 1:1; 6:15-23), his direction to a runaway slave to return to his master (Philemon), and his apparent lack of opposition to the whole system of Roman slavery. Although Paul’s views on women and thus his larger theological system are “redeemable” for some feminist theologians when read in new ways,[4] others see Paul’s thought as so hopelessly opposed to the leadership of women in the church that Paul and indeed the Bible in general must be rejected.[5]

Perhaps Paul still suffers from a strange malady identified by Robin Scroggs: “The trouble with Paul is that he has too many friends and too many enemies. The one thing that the friends and enemies tend to have in common is that they do not really know what Paul is all about. At least the Paul I hear defended and the Paul I hear attacked is not the Paul that I have come to know and appreciate.”[6]

A NOTE ON TERMS

Israel’s Bible instead of Old Testament

The term Old Testament is frequently used to designate the portion of the Christian Bible that includes the documents from Genesis to Malachi (in the Protestant Bible). Paul, of course, did not have the Christian Bible, and the documents that were available to him were not known as the “Old Testament,” since there was as yet no “New Testament.” Generally, he used the Greek translation of Israel’s authoritative scriptures, but he also had knowledge of the Hebrew. It is therefore misleading to refer to Paul’s use of the Old Testament, the Greek Old Testament (over against the Hebrew Bible), or the Hebrew Bible (over against the Greek translation). For those reasons, this study will use the terms Israel’s Scriptures, Israel’s Bible, Judean Scriptures, and Judean Bible to refer to this body of writings. Paul ordinarily called them simply hai graphai, “the writings” or “the scriptures,” or hē graphē, “the writing” or “the scripture.”

Judean instead of Jew

For many years, English-speaking people have translated the Greek word Ioudaios as Jew. Recently, scholars have questioned that decision, arguing that the term Jew ought not to be used to translate first-century documents like the New Testament. Philip Esler is an articulate representative of that approach.[7] His basic argument is that ancient Greeks named ethnic groups in relationship to the territory in which they or their ancestors originated—whether or not they still resided there, or even if they had never resided there. Romans, too, almost always identified ethnic groups in the same way, as did the people of Israel.[8]

The Greek student will recognize in the word Ioudaios the geographical place name Ioudaia, or Judea. Ioudaioi (Judeans) are people from Ioudaia (Judea)—because either they or their ancestors were born there. (Compare in the United States people who proudly bear their ancestral home in their preferred designations as Irish Americans, Chinese Americans, or Americans of African descent.) In the case of Judeans who lived outside Judea, many ties continued to bind them to Judea: they paid the temple tax to the temple in the Judean capital city of Jerusalem, they often celebrated feasts when Jerusalem celebrated them, and they prayed facing Jerusalem.

Esler offers several supporting arguments:

- Judean retains by its very name the connection with the temple and the ceremonies practiced there.

- Jew , in contrast, signals an identity based not on the temple and its sacrificial system, which were still very much alive during Paul’s lifetime, but a later form of Judaism in which identity centered around the Torah (Law).

- Also, the term Jew carries for modern readers many later connotations, such as the persecution of Jews in medieval Europe and, above all, the twentieth-century Holocaust under the Nazis, that were not part of the experience of first-century Ioudaioi ....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table Of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Map of Paul's World

- Part 1 Figures

- Introduction: Why Study Paul?

- Who Was Paul and What Did He Do?

- What Did Paul Write?

- Glossary

- Abbreviations