- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Short Introduction to the Hebrew Bible

About this book

A marvel of conciseness, John J. Collins's Short Introduction to the Hebrew Bible is quickly becoming one of the most popular introductory textbooks in colleges and universy classrooms. Here the erudition of Collins' renowned Introduction to the Hebrew Bible is combined with even more student-friendly features, including charts, maps, photographs, chapter summaries, illuminating vignettes, and bibliographies for further reading. The second edition has been carefully revised to take the latest scholarly developments into account. A dedicated website includes test banks and classroom resources for the busy instructor.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Short Introduction to the Hebrew Bible by John J. Collins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Criticism & Interpretation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 11

1 Samuel

In this chapter we examine the First Book of Samuel. Different threads of the story—the earlier narrative of the birth and call of the prophet Samuel, the story of the Ark of the Covenant’s capture and recovery, the move to an Israelite monarchy and the trials of the king, Saul, and David’s early career in Saul’s court and then as an independent mercenary and outlaw—are all part of the story of David’s rise to power. As we shall see, different narrative interests are at work in the story.

The two books of Samuel were originally one book in Hebrew. They were divided in Greek and Latin manuscripts because of the length of the book. In the Greek, the Septuagint (LXX), they are grouped with the books of Kings as 1–4 Reigns. The Greek text of Samuel is longer than the traditional Hebrew text (MT). Some scholars had thought that the translators had added passages, but the Dead Sea Scrolls preserve fragments of a Hebrew version that corresponds to the Greek. It is now clear that the Greek preserves an old form of the text and that some passages had fallen out of the Hebrew through scribal mistakes.

There are various tensions and duplications in 1 Samuel that are obvious even on a casual reading of the text. Samuel disappears from the scene in chapters 4–6, and then reemerges in chapter 7. In chapter 8 the choice of a human king is taken to imply a rejection of the kingship of YHWH. Yet the first king is anointed at YHWH’s command. There are different accounts of the way in which Saul becomes king (10:17-27; chap. 11) and different accounts of his rejection (chaps. 13 and 15). There are two accounts of how David came into the service of Saul (chaps. 16 and 17). David becomes Saul’s son-in-law twice in chapter 18, and he defects to the Philistine king of Gath twice in chapters 21 and 27. He twice refuses to take Saul’s life when he has the opportunity (chaps. 24 and 27).

The Deuteronomistic editor does not seem to have imposed a pattern on the books of Samuel such as we find in Judges or Kings. Deuteronomistic passages have been recognized in the oracle against the house of Eli in 1 Sam 2:27-36 and 3:11-14, in Samuel’s reply to the request for a king in 8:8, and especially in Samuel’s farewell speech in chapter 12. The most important sign of editorial activity is the presence of two quite different attitudes to the monarchy. First Samuel 9:1—10:16; 11; 13–14, had a generally favorable view of the monarchy. Chapters 7–8; 10:17-27; 12; 15, viewed the kingship with grave suspicion. The easiest explanation is that the first Deuteronomistic edition in the time of Josiah was positive toward the monarchy, and that the more negative material was incorporated in a later edition during the exile, after the monarchy had collapsed. Both editions may have drawn on older traditions. The net result, however, is a complex narrative that shows the range of attitudes toward the monarchy. The historical accuracy of these stories is moot, since we have no way of checking them. They have the character of a historical novel, which clearly has some relationship to history but is concerned with theme and character rather than with accuracy in reporting.

The Birth and Call of Samuel (1:1—4:1a)

The story of Samuel’s birth is similar to that of Samson’s, but more elaborate. His mother Hannah is barren, but eventually the Lord answers her prayer and Samuel is conceived. In thanksgiving, Hannah dedicates her son as a nazirite to the Lord. Unlike Samson, who was also a nazirite, Samuel is dedicated to service at the house of the Lord at Shiloh. Psalm 78:60 describes the shrine at Shiloh as a miškan, or tent-shrine, and Josh 18:1 and 19:51 refer to the tent of meeting there. Some scholars have argued that the tabernacle described in the Priestly source was located at Shiloh.

The Song of Hannah in 1 Samuel 2 is a hymn of praise, which refers to God’s ways of dealing with humanity rather than to a specific act of deliverance. It was probably chosen for this context because of v. 5: “The barren has borne seven, but she who has many children is forlorn.” The theme of the song is that God exalts the lowly and brings down the mighty. Hannah’s song is the model for the Magnificat, the thanksgiving song of the virgin Mary in the New Testament (Luke 1:46-55).

The manner of Samuel’s birth links him with the judges. His call anticipates that of the later prophets. The call of the prophets takes either of two forms: it can be a vision (Isaiah 6; Ezekiel 1), or it can be an auditory experience (Moses, Jeremiah). Samuel’s call is of the auditory type. Unlike Moses or Jeremiah, however, Samuel is not given a mission. Rather, he is given a prophecy of the destruction of the house of Eli. The revelation establishes his credentials as a prophet. We shall find that he functions as a prophet in other ways. He is a seer, who can find things that are missing (chap. 9). In 1 Sam 19:20, he appears as conductor of a band of ecstatic prophets. More importantly, he anoints kings and can also declare that they have been rejected by God. Samuel’s interaction with Saul prefigures the interaction between kings and prophets later in the Deuteronomistic History.

The Ark Narrative (4:1b—7:1)

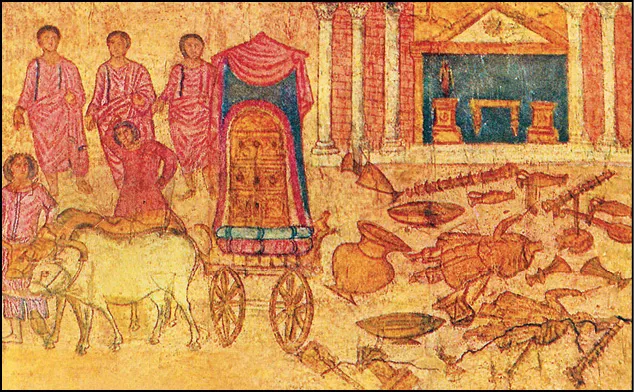

The story of Samuel is interrupted in 4:1b—7:1 by the story of the ark, in which he plays no part. The ark is variously called the ark of God, the ark of YHWH, the ark of the covenant, or the ark of testimony. In Deut 10:1-5 Moses is told to make an ark of wood as a receptacle for the stone tablets of the covenant. The story in 1 Samuel 4–6, however, makes clear that it is no mere box. It is the symbol of the presence of the Lord. It is carried into battle to offset the superior force of the Philistines, in the belief that YHWH is thereby brought into the battle. But YHWH’s enemies are not scattered before him. The capture of a people’s god or gods, represented by statues, was not unusual in the ancient Near East. Nonetheless, the capture of the ark in battle was a great shock to the Israelite and led directly to the death of Eli.

The story of the ark, however, has a positive ending for the Israelites. YHWH mysteriously destroys the statue of the Philistine god Dagon and afflicts the people with a plague. As a result, the Philistines send back the ark. Nonetheless, it is significant that shortly after this episode the Israelites begin to ask for a king. The old charismatic religion of the judges, which relied heavily on the spirit of the Lord, was not adequate for dealing with the Philistines.

The Move to Monarchy (1 Samuel 7–12)

Samuel reappears on the scene in 1 Sam 7:3, and is said to judge Israel after Eli’s demise. Unlike the older judges, however, he is not a warrior. He secures the success of the Israelites in battle by offering sacrifice.

Like Eli, Samuel has sons who do not follow in his footsteps, and so the people finally ask for a king. The exchange between Samuel and the people in 1 Samuel 8 represents the negative view of the kingship. The people are said to have rejected YHWH as king. Moreover, the prediction of “the ways of the king” reflects disillusionment born of centuries of experience and is quite in line with the critiques of monarchy by the prophets, beginning with Elijah in 1 Kings 21.

Fig. 11.1 The Ark of the Covenant and the broken statue of the Philistine god Dagon; fresco from the third century c.e. synagogue at Dura-Europos. Commons.wikimedia.org

There are two accounts of the election of Saul as the first king. The first is a quaint story in which he goes to consult the seer Samuel about lost donkeys. This story speaks volumes about early Israelite society. Lost donkeys were a matter of concern for prophets and for future kings. This is the first case in which a king is anointed in ancient Israel. The king was “the Lord’s anointed” par excellence. It is from this expression that we get the word “messiah,” from the Hebrew mashiach, “anointed.”

According to the second account of the election of Saul, he was chosen by lot (1 Sam 10:20), the formal method for discerning the divine will favored by the Deuteronomists. Also distinctively Deuteronomistic is the notice that Samuel wrote the rights and duties of the kingship in a book and gave it to Saul (compare the law of the king in Deut 17:14-20). Initially, Saul acts like a judge, summoning the tribes by sending around pieces of oxen, and being inspired by the spirit of the Lord. After the victory over the Ammonites, the people assemble at Gilgal to make him king. There are several steps, then, in the process by which Saul becomes king: divine election, designation by a prophet (Samuel), and finally acclamation by the people.

The accession of Saul is completed by the apparent retirement of Samuel in chapter 12. Samuel’s protestation of innocence provides a concise summary of the conduct expected from a good ruler. He should not abuse the people by taking their belongings, or defraud them, and he should not take bribes to pervert justice. Samuel seems reluctant, however, to yield the reins of power. He chides the people for asking for a king. In the end he grants that things will be all right if they do not turn aside from following the Lord. What is important is keeping the law, regardless of whether there is a king.

The Trials of Saul (1 Samuel 13–15)

Samuel does not stay retired. He clashes with Saul in two incidents, in chapters 13 and 15. The first concerns the preparation for a battle against the...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Maps

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- The Near Eastern Context

- The Nature of the Pentateuchal Narrative

- The Primeval History

- The Patriarchs

- The Exodus from Egypt

- The Revelation at Sinai

- The Priestly Theology

- Deuteronomy

- Joshua

- Judges

- 1 Samuel

- 2 Samuel

- 1 Kings 1–16

- 1 Kings 17—2 Kings 25

- Amos and Hosea

- Isaiah

- The Babylonian Era

- Ezekiel

- The Additions to the Book of Isaiah

- Postexilic Prophecy

- Ezra and Nehemiah

- The Books of Chronicles

- The Psalms and Song of Songs

- Proverbs

- Job and Qoheleth

- The Hebrew Short Story

- Daniel, 1–2 Maccabees

- The Deuterocanonical Wisdom Books

- From Tradition to Canon

- Glossary