Sidney W. Mintz’s Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History, published in 1960, is a classic text in anthropology. It follows the life and travails of Anastacio (Taso) Zayas Alvarado, a cane worker of poor origins and dismal prospects who from his childhood was destined for the crushing manual labor typical of Caribbean sugarcane plantations. This is, sadly, the story of many Latin Americans who struggle to overcome grievous poverty while striving to confer meaning to a human existence at the margins of any social hierarchy.

Most scholars who examine the text stress the futile efforts of Taso Zayas to forge a brighter economic future for his family. But they frequently have disregarded what truly astounded Mintz: Zayas’s unexpected conversion to Pentecostalism. From that dramatic religious experience arose Zayas’s profound conviction that, despite the severe social conditions of his life, his existence had now gained an eternal significance, and he had been blessed with heavenly salvation, had become a child of God and temple of the Holy Spirit.

This story of extraordinary healing, both physical and spiritual, gives us a view into the sudden and dramatic irruption of Pentecostal Christianity in Latin America. This charismatic way of conceiving of and living the Christian faith has transgressed the boundaries of what for centuries had been the normative dogmatic and ecclesiastical expression of Christianity in the region. It has reconfigured the self-understanding, family life, and communal existence of millions of working-class men and women. In short, it is a narrative of unexpected transformation that in its particularity becomes paradigmatic of a religious revolution for Latin American Christianity.

Mintz’s initial interest in Taso Zayas’s life had nothing to do with religiosity. Neither the scholar nor Zayas seemed to care much about sacred issues, matters of doctrine, liturgical rites, or theological creeds. Mintz’s scholarly concern was typical of the mid-twentieth century, namely, how the process of modernization and industrialization affected and shaped the existence of rural workers. Taso was one of a multitude of men and women in Latin America who lacked schooling, land, and house, who from cradle to grave were in bondage to an accelerated capitalization of one product, geared toward export and controlled by foreign corporations. In the Caribbean during the first half of the twentieth century, that meant sugarcane. The region had become a huge plantation devoted to sweetening the consumption habits of metropolitan cities all over the world while embittering the lives of so many native workers, modern versions of the African slaves who used to sweat and die in the fields of the islands.

Taso Zayas was nothing more than another worker at a sugarcane plantation, constantly striving and yet failing to make ends meet as he worked from sunrise to sunset to provide food and clothing for his common-law wife, Elizabeth, and his twelve children, of whom three died in their early childhood. Fatherless at the age of ten months (in 1908) and motherless when he was twelve (1920), he suffered from painful aches caused by the hard labor he had to perform daily. His domestic life was plagued by continual bickering with Elizabeth—not exactly an image of happiness and comfort of any kind.

Zayas was not a passive pawn in the winds of social destiny, for at times he was very active in Puerto Rico’s general confederation of workers and in the reformist Popular Democratic Party. The 1940s were for him a decade of intensely felt social disillusionment, followed by bitter frustrations. Everything promised to change; everything remained the same. Zayas did not seem to fit well into the social patterns of power struggles. Labor union organizing and political activism resembled Sisyphus’s curse.

Yet in 1950, as he was plagued by poverty, pain, and frustration, something astonishing happened in Zayas’s life: a radical disruption of his previous self-understanding and existence. As was so frequent though paradoxical in Latin American patriarchal society, the women of the house took the first step. Elizabeth and their oldest daughter, Carmen Iris, went to a Pentecostal healing crusade. They came back with amazing stories of miraculous healings, charismatic happenings, and conversions. Extraordinary events seemed to be taking place, bringing joy where suffering prevailed and hope where despair ruled.

Elizabeth’s life was haunted by the sinister memory of her father, who had drunk heavily and mistreated her mother, and by her constant fights with Taso, caused by her suspicions about his possible dalliances with other women. One night in the midst of a Pentecostal revivalist session, she felt herself possessed by a supernatural power that gave her the exceptional capability of speaking in tongues. The preacher’s interpretation, to the joyful exclamations of the congregation, was that Elizabeth had been baptized by the Holy Spirit. She had been transformed into a new creature, her soul had been redeemed, and she was assured of eternal salvation.

Mintz was astute enough to perceive the significance of female priority in the religious conversion of this family. Indeed, as happens throughout Latin America, conversion to evangelical Protestantism or to Pentecostalism usually entails a sweeping reconfiguration of family life. It is probably too much to claim that it fundamentally alters the patriarchal hierarchy of authority, for the biblical literalism to which it is closely linked is suffused with notions of masculine primacy. But it frequently transforms the patterns of behavior of the husband/father, who adopts a sterner moral discipline and now abstains from investing money and energy in drinking, womanizing, and betting. The patriarchal hierarchy might be left in place and even theologically reinforced by biblical allusions to female submission in the New Testament epistles (1 Cor. 14:34, Eph. 5:22, Col. 3:18, 1 Tim. 2:11-12, 1 Pet. 3:1), but the shape of masculine behavior is nonetheless substantially reconfigured. The patriarchal household code acquires a benevolent aspect.

Zayas had always considered himself Roman Catholic, but throughout his life he had regarded church activities as something alien to his daily labors, sorrows, and illusions. He heard with some reservations the strange stories narrated by his wife and daughter but decided to attend one of the evangelistic campaigns of a visiting North American preacher. As the evening progressed, Zayas experienced something strange and unexpected: “Brother Osborn began to pray for the sick. . . . I felt something in my body, a thing—an extraordinary thing—while he was praying for the sick. And later, after he finished that prayer, I felt an ecstasy—something strange. . . . And afterward I did not feel that pain that I had been feeling. . . . And up to the present, thank God, I have never felt that pain again.”

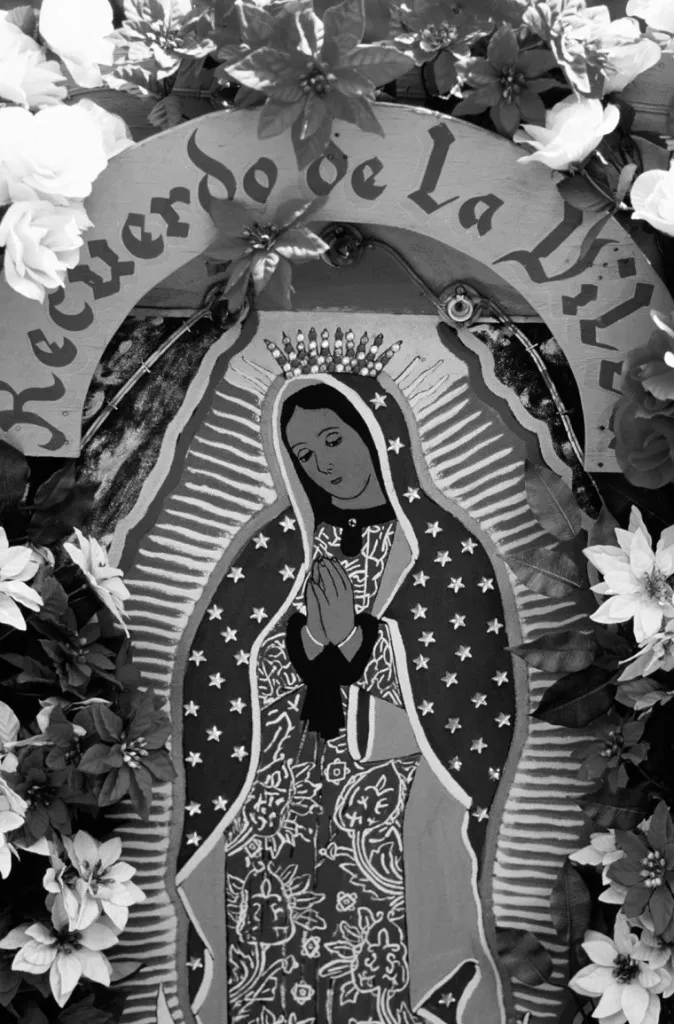

Miraculous healing is nothing new in Latin American religious traditions. There are several sites considered sacred, where healing divine grace is implored and received. The most famous of all is the basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe, in Mexico. The basilica brims with thousands of ex-votos of gratitude for the healing miracles performed by the Guadalupe. Since her first alleged appearance to the indigenous man Juan Diego, in December 1531, countless acts of divine healing have been attributed to the Patroness of Mexico and Latin America. Though the Guadalupe has also fulfilled a meaningful role in the formation of the Mexican national identity, it is probably true that common people throughout Mexico, Latin America, and the Hispanic diaspora in the United States look to the Virgin more as a maternal source of extraordinary favors in situations of grave distress than as a patriotic icon.

Miraculous healings are usually attributed to a holy person, most of the time the Mother of Christ, and happen in a sacred place, in this case the Tepeyac. Both the holy person and the place are linked to a sacred myth of origin that first circulated orally and then was recorded in writing. Zayas’s healing, however, belongs to a different genre. Stories now abound in Latin America of healings that occur in many scattered places, with no sacred myths of origin, performed after the intercessory prayers of evangelists unrecognized by mainstream churches. Such healings take place under the aegis of churches and congregations of relatively new origins and picturesque names (such as Iglesia del Buen Pastor, Iglesia del Getsemaní, Fuente de Agua Viva, Roca de Salvación), many of them founded by self-appointed preachers. They might take place anywhere—a football stadium, a recently opened storefront church, the town square, places not usually considered sacred—and are performed by ministers not accredited by any theological academy or any of the traditional Christian confessions. One might speak of a radical democratization and popularization of divine healing.

The healings are usually perceived as extraordinary events. But as happens so frequently in the history of the Christian faith, this movement is also a process of the retrieval of a tradition not entirely erased from the memory of the believing community. After all, miraculous healings abound in the Gospels and the chronicles of the first apostles. “Signs and wonders” (John 4:48) were part and parcel of the early Jesus movement and were considered indications of a decisive irruption of divine power and mercy ...