At a Glance This chapter will introduce a method for planning the specific structure of each collaborative learning session. - Brief narrative of a collaborative networked learning session

- Incorporating technologies for a collaborative networked pedagogy

- Evaluating technologies for collaborative teaching and learning

- Introducing the session-planning template

- Effective collaborative engagement during networked sessions

|

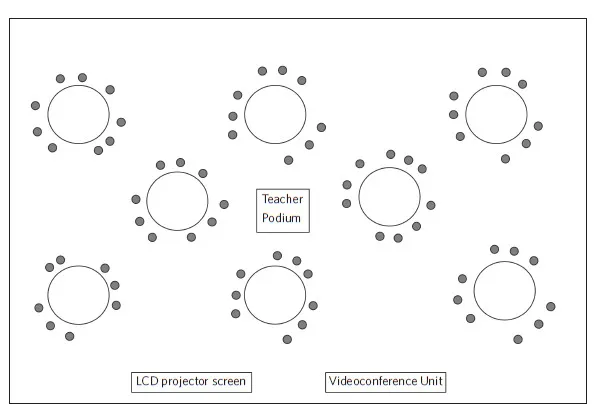

At 09h30 EDT (UTC: – 4 hours), TeacherZ leaves her office for her classroom; but along the way, she stops in at her building’s IT center to pick up the mobile videoconferencing cart. Seeing someone familiar in the halls, she asks for help to guide the device into her classroom. By the time she arrives, there are people already filtering into the room, which itself has round tables that seat roughly ten people, and on each table are three desktop computers. After plugging in the videoconferencing unit and pressing the power button, she connects the cables in the manner shown to her during the presession testing demo where her institution’s IT person was present. While the videoconferencing unit powers up, she moves over to the teacher podium in order to turn on the room’s computer and LCD projector.

TeacherZ continues to casually welcome people entering the room while writing the session’s learning goals, a set of basic instructions, and a list of activities on the whiteboard. By this time, 09h45, the room is full with people pulling up chairs, chatting with colleagues, and setting out their writing pads. A few have laptops, and most of them have smartphones that they periodically check.

TeacherZ has a smartphone, too, and she sends a text message to TeacherA, telling him that she will be ready to connect at 10h00. TeacherA texts back to say, “Great! I will call to connect our VCU to yours.” Using smartphone messages is the backchannel that these collaborators have agreed upon for communication outside the view of their learners. In the next five minutes, TeacherZ logs into Google Drive and opens the documents that will be used for the class session.

At 10h00 a call comes in on the videoconferencing unit. TeacherZ answers, and the other class appears. Both groups of students are not paying attention to the screen; the teachers have agreed to have their videoconference connection muted until they are ready to begin the actual session. By doing this, they are mitigating the potential for a cacophony of people getting settled into class.

TeacherZ calls for everyone’s attention, and she confirms that today’s class will be a collaborative networked learning session. She refers to the fact that they can see TeacherA doing something likewise on the videoconference screen. TeacherZ asks everyone to power up the desktop computers at their tables, and then she briefly confirms the basic guidelines for collaborative networked sessions. Near the beginning of the term, these guidelines were co-created by the two classes themselves as a sort of “collaborative networked learning contract.” That was their first experience working in real time to create an online document, but by now they are very familiar with that kind of activity.

Someone mentions that it looks like the other class is ready. TeacherZ confirms this with a text message to TeacherA, who gives a “thumbs up” through the videoconference connection. It is now 10h10, but these extra minutes to ensure preparation help everyone feel as though the session will not be rushed, especially the teachers! Both teachers unmute their videoconferencing units, and begin a short discussion of the session’s learning goals, basic instructions, and activities.

During Skype conversations to prepare for the session, the teachers agreed upon these and assembled everything needed for the session with online documents. These were circulated to the class earlier, along with the short video and text that the teachers expected their classes to review. Both teachers could see on their shared online platform that the learners had indeed posted short personal responses to the video and text. Many had posted their responses at the last minute using their smartphones. This was to be expected; but in any case, a basic activation to the session topic was already in place.

Teacher Z’s Classroom Set-up

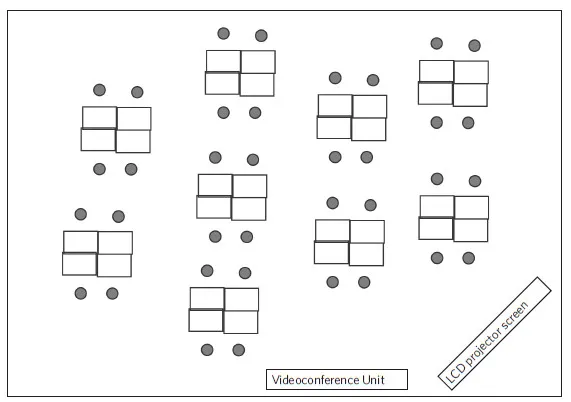

Teacher A’s Classroom Set-up

After the session overview, TeacherA takes over to initiate the first activity. Considerable thought was put into the positioning of the videoconference unit at an earlier point in time. Each teacher positioned the unit’s camera so that they could address both sets of students without putting their backs to either group. They had also obtained a long extension-corded microphone that they placed in the center of their rooms. While the microphone transmits almost all classroom sounds, this also means that both groups can casually discuss a topic together and hear each other perfectly. At one point in the term, everyone laughed when a “phantom sound” was emitted. No one in either room took responsibility!

The first activity is a version of “think-pair-share.” It is based on the responses that were posted, where groups from each class are to review and summarize the responses of their classmates across the videoconference connection. This activity is accompanied by an instruction sheet that guides the learners in how to process the responses and what, specifically, the teachers are asking them to be sure to remark upon. After roughly five minutes, each group comes up to the videoconference unit and stands in a manner similar to their teachers. A series of brief conversations ensue, where groups confirm or add to what others have ascertained. The topical activation is accomplished. Everyone understands what they are discussing and the framework that the teachers are asking them to use for processing the topic.

The time is now 10h45, and there is only another twenty-five minutes remaining in the class session. TeacherA texts TeacherZ to ask about initiating the next activity. There is not a lot of time remaining in the class session, since there was more time used than expected by the introduction, explanation, and activation activity. The teachers agreed in advance, however, not to rush through the session plan. This can only lead to the kinds of misunderstandings and frustrations that lead to the breakdown of communication and collaboration. In the planning phase, the teachers did discuss how the main activity could be initiated in one collaborative networked session, and then completed in a future class session. Given the situation, TeacherZ texts to say that she will initiate the next activity and also to inform the classes that the activity would be completed in the next class session.

TeacherZ asks for everyone’s attention, and then directs the classes to an online location with folders for each set of groups. Inside their folder are document, spreadsheet, and video files. As a larger group spanning both locations, each folder’s contents outlines a case study and problem to be addressed. The learners are asked to follow the guide to create a solution to the problem collaboratively. The explanation of their solution is to be presented graphically, using an online presentation platform.

Each small group is made up of learners from the different geographical locations. In order to facilitate their communications with each other without creating cacophony in actual classrooms, the learners use the “chat” function built into the Google Docs interface. The chat facilitates the spontaneous, real-time conversations within each group. The “insert comment” function is used when a learner wishes to suggest a substantive piece of text or to identify a revision. In this manner, the screens show a fast-scrolling chat as learners communicate back and forth. The room is filled with the chatter of keyboards. Slowly but surely, the documents begin to fill in with text, images, tables, and graphs.

Extend the Innovation 5.1

G. Brooke Lester There’s nothing quite like watching a Google Doc take shape, at multiple hands, in real time, like a self-organizing work of art, don’t you find? In 2012, as part of Digital Writing Month (or #DigiWriMo), aspiring digital artists descended onto Twitter and Google Docs, collaborating to write a poem in thirty minutes. Emboldened by their success, organizers Jesse Stommel and Sean Morris facilitated a similar poetry-writing event in 2014, this time with the added twist that participants were free to change the rules midevent. Oh, and there were a couple of novels, one about a duck. This is all to say, go ahead and go nuts. A Google Doc allows as many as fifty contributors to collaborate simultaneously in a single document. As Loewen notes, “back channels” abound to facilitate the action: Google Docs’ own built-in chat client, text messaging, Twitter, and so forth. You’ve got your networked classrooms together, so honor that synchronous moment by letting the learners get raucous together and learn by building. |

After setting the videoconference units to “mute,” the cross-class groups set to work, and TeacherA and TeacherZ circulate virtually through the online presentation platform and its chatting function. The teachers are thereby able to assess each group’s progress; by texting each other, they are able to plan out coordinated interventions with each group. Affirmations, reminders, and suggestions are given to the...