It is one thing to recognize how the cross was being formed in the mental imaging of two early Christian authors. It is another thing to find those mental images transferred to ancient artistic media. This chapter surveys most of the material evidence testifying to the cross as a devotional symbol among pre-Constantinian Christians. It will demonstrate that, even in the pre-Constantinian era, the cross was employed by Christians as a visual, artistic symbol of their faith. The cross was not simply formed in conceptual images enjoyed by the mind. Instead, at times it became concretized as a visual symbol, an image embedded within artistic media.

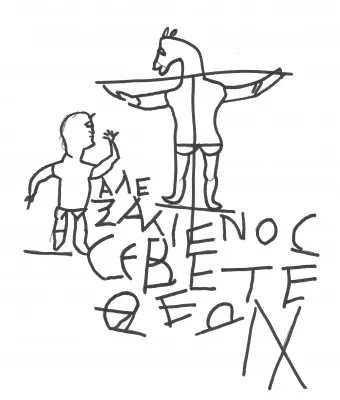

The cross is depicted in various third-century inscriptions from the city of Rome and its environs in the pre-Constantinian period. One of these inscriptions is commonly referenced in discussions of early Christianity. Found on the Palatine Hill near the imperial residence in Rome, it portrays a person by the name Alexamenos in the process of worshiping his deity, and dates perhaps to the early third century. The deity depicted is not one of the traditional Roman deities but one hanging on a cross, a cross in the shape of a Τ. The tone of this inscription is one of mockery, as seen by the fact that the inscriber has depicted the crucified deity as having the head of a donkey (see fig. 5.1)—referencing the view that Christians worshiped a donkey-headed deity (see Minucius Felix, Octavius 9.3; 28.7; Tertullian, Apology 16.12). One interpreter imagines this inscription, which features the words “Alexamenos worships his deity” or “Alexamenos, worship [your] deity,” to have been “drawn by a palace page with cruel schoolboy humor to mock the faith of a fellow slave.”

Does this artifact have any significance regarding Christian use of the cross? The common view is that it does not. Instead, it merely shows that non-Christians knew enough about Christian beliefs to mock the notion of a crucified deity. But even if this is all that the Alexamenos inscription reveals, that much is at least suggestive; if Christians were trying to hide the crucifixion of Jesus from their contemporaries, they were not doing a very good job of it.

Figure 5.1. A reconstruction of the Alexamenos inscription.

But does the Alexamenos inscription do more? Does it suggest that the cross was recognized as a Christian symbol prior to Constantine? Some, such as Felicity Harley-McGowan, think that it does. In her study of early Christian depictions of crucifixion, Harley-McGowan writes:

This visual conception of a crucifixion . . . suggests a “pagan,” or non-Christian’s awareness of two things: firstly, the significance of Jesus’ Crucifixion (at least in terms of it being a powerful and efficacious symbol); and secondly, a consciousness of the existence of Christian representations of the crucifixion by the early 3rd century AD.

“Crucifixion,” “powerful symbol,” “representations,” “early third century”—these terms are rarely placed together in positive relationship when discussing the cross prior to Constantine. But they represent one historian’s challenge to a long-standing view about the absence of the cross in pre-Constantinian forms of Christianity.

The Alexamenos inscription notwithstanding, other evidence from the environs of Rome leads us toward the same conclusion. In 1919 an underground sepulcher was discovered on the Viale Manzoni in Rome, west of the Porta Maggiore. It contains several tomb chambers. A mosaic was found in one of the chambers, commemorating some individuals of free status from among the Aurelia household. They are said to be “brothers,” although the list mentions not only men (i.e., Onesimus, Papirus, and Felicissimus) but also one woman (Prima, said to be a virgin). Within the chambers of the Aurelii sepulcher is a considerable amount of artwork, most of which has a religious dimension. One painting is of significance. It depicts a man whose right hand points directly to a body cross. According to William Tabbernee, this “is a clear indication of Christianity.” The sepulcher is dated to a time before 282 ce.

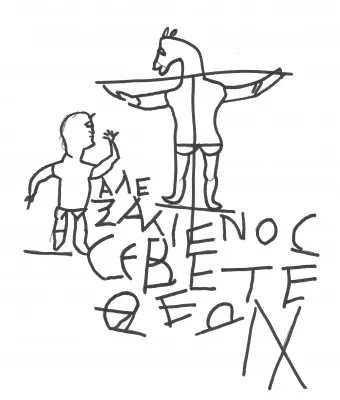

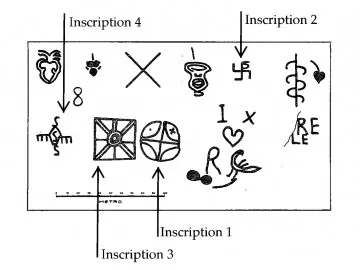

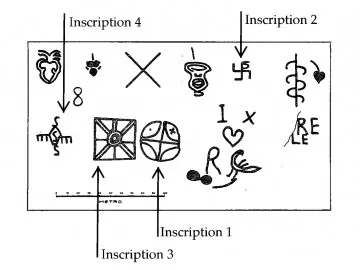

Just beyond Rome, in its closest port city, Ostia, a group of symbols were incised into one area of flooring in room 6 of the Baths of Neptune (region 2, insula 4; see fig. 5.2). The symbols etched by users of this public room appear in figure 5.3.

Figure 5.2. Room 6 of the Ostian Baths of Neptune.

Figure 5.3. Christian symbols in room 6 of the Baths of Neptune in Ostia.

In his definitive study of Ostia Antica, Giovanni Becatti, an eminent archaeologist from the mid-twentieth century and onetime director of excavations at Ostia Antica, claims that these inscriptions are Christian symbols (an interpretation shared by Ostian scholar Jan Theo Bakker). Whether that is true for all the inscriptional marks on this floor, it is nonetheless notable that (as I will demonstrate in the paragraphs below) at least four of these symbols incorporate the symbol of the cross, one of which incorporates the name Jesus while another incorporates a variant form of a Christian staurogram.

Note, for instance, how the shape of an equilateral cross serves as the scaffolding for one of the most interesting of all the cross formations among these symbols—inscription 4. Although inscription 4 looks like a series of artistic scribbles, it unpacks to spell out the Latin word Iesus, or “Jesus,” twice—with the clever styler of this fascinating construction having laid the letters along the two axes of an equilateral cross. It is constructed in the following fashion, from left to right (compare also fig. 5.4):

- I (a single stroke)

- E (two vertical strokes, connected to the I by a horizontal line above the three vertical strokes)

- S (in the middle)

- U (beneath the middle S)

- S (below the middle S).

The pattern then repeats from other side with inverse procedures (so that the second U appears upside-down), with the center S doing double duty.

Figure 5.4. The Ostian “Iesus” inscription (“inscription 4”), built up

stage by stage.

In fact, the same word could have been spelled out in the same cross formation but using slightly different formations for the first two letters. In this option, the letters I and E lay on their side as a ligature, without the need for an overstrike joining them. In this scenario, two other patterns (patterns 3 and 4) form the name Iesus twice, in the shape of the cross (fig. 5.5).

Figure 5.5. An alternative version of the Ostian “Iesus” inscription (“inscription 4”), built up stage by stage.

Perhaps only the combination of patterns 1 and 2 was intended, or perhaps only the combination of patterns 3 and 4. Perhaps both combinations would have been recognized simultaneously. But despite this uncertainty, we can be sure that the pre-Constantinian Christian who devised this extremely clever inscription was drawn to the shape of the cross as the backbone for his ingenious theological artistry.

The cross also serves as a backbone for other inscriptions in this room, such as inscription 1, the large circular shape in the center of Becatti’s lower line of figures. A smaller equilateral cross is also found, slightly tilted, at the top right of that same circular construction. Inscription 2 foregrounds a gamma cross, with the Greek letter gamma (Γ) spiraling out four times from a midpoint, and with one appendage also having a Greek letter rho emerging from it—an attempt to build a staurogram within a gamma cross instead of the usual and more natural T cross. The cross appears also in inscription 3, the square shape next to inscription 1, which seems to combine both an equilateral cross and a chi within a square frame adorned with a circle in its center point.

Evidently, then, the symbols on the floor of room 6 in the Ostian Baths of Neptune include among their number five crosses deriving from Christian devotion (with inscription 1 containing two crosses). In fact, of the various symbols assembled in that location, the cross is the predominant shape. Moreover, these crosses are embedded in quite different structures in ea...