Anders Klostergaard Petersen

Wie alles sich zum Ganzen webt,

Eins in dem Andern wirkt und lebt!

—Goethe, Faust, v. 447f.

Initially, it may appear rather banal—verging on a tautological statement—to proclaim that Paul the Jew was also Paul the Hellenist. After all, have we not—following in the aftermath of Martin Hengel’s erudite work, Judentum und Hellenismus, and the scholarly discussions it gave rise to, also with respect to the interpretation of the emergence of formative Christ-religion and its texts—had almost half a century of studies that have been careful to highlight how Paul’s Judaism should not be understood as exclusive of his Hellenism and vice versa? Nevertheless, the argument that I shall develop in this chapter may not be as trivial as it sounds on a first hearing. Despite the fact that we have had almost fifty years of discussion pertaining to the Judaism/Hellenism debate and thirty years of intense scholarly exchange on Paul’s respective Hellenism and Judaism, I do not think that we have come far enough in terms of the theoretical underpinning and methodological subtlety that the question demands. Although scholars are often prone to emphasize the necessity of moving beyond the conceptualization of the problem in terms of a dualism, or, worse, a dichotomy, the binary formulation—still coming close in many cases to a dichotomization of the two entities—still characterizes much current work. Paul the Jew is frequently played out against Paul the Hellenist and the other way around.

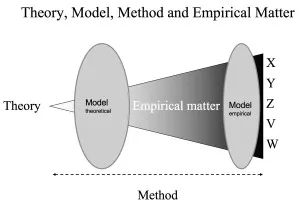

Some of this may have to do with difficulties pertaining to an inescapable “aspectualism”: a study focused on Paul’s relationship to Stoicism or Greco-Roman philosophy of a popular kind will find it hard to place simultaneous emphasis on Paul’s Jewishness. Owing to the perspective one projects onto the world, there is a certain and obvious limit to how much one can encapsulate. That said, however, I think there is more to the question than having to make an inevitable choice when selecting a particular empirical focus for one’s study. It is not only a matter of choosing sides or refraining from doing so, but a far more thorough question with important theoretical ramifications for how we ultimately understand culture and the relationship between different cultural entities—whether in the current world or in that of antiquity. In addition, this initial question also determines the methods to be applied in order to make the simultaneous double movement from the theoretical perspective to the empirical matter segmented by that particular view and back again. This also has significant consequences and implications for the models to be used, whether they are of a more abstract (for instance, culture or religion perceived as a system) or a more concrete nature (culture or religion understood in terms of a kinship metaphor). It is through such models that we filter the theoretical perspective (see the figure below, which is meant as an iconic representation of the ideal relationship between theory, method, models, and empirical matter).

Due to space constraints, I shall confine my discussion to three aspects with respect to which I want to provide a rejoinder to the current debate on Paul’s relationship to Judaism and Hellenism or Greco-Roman culture. The three aspects are intrinsically related in terms of overall theoretical perspective. Additionally, I have decided to direct my attention to issues of a more theoretical nature, important for the discussion of Paul’s relationship to Hellenism and Judaism. Since I got the impression that the first papers circulated at the conference underlying this volume were predominantly focused on empirical matters, I thought it beneficial to also have a contribution that concentrated more specifically on the discussion of various theoretical matters pertinent to the comparison between Paul’s purported Hellenism and Judaism and the manner of staging the problem. It is to this question that I devote the rest of my chapter.

Provisional Sketch of the Three Main Issues

First, I think it is pivotal to explore how we may possibly refine our thinking about culture. Such an endeavor is crucial in order to develop a terminology and a concomitant manner of conceptualizing the relationship between what appear to us as different cultural trajectories, and to avoid the problem of turning Paul’s alleged Judaism and Hellenism into a zero-sum game. Despite all allegations to the opposite, it is hard to avoid the impression that this is, in fact, the practical upshot of numerous studies in which the demonstration of one cultural entity is ultimately conceived of as a corresponding lack of the other. Similarly, and as a reasonable objection to my line of thought, it may be argued that if we turn Judaism and Hellenism into excessively general, and, therefore, fuzzy categories, we are no longer able to make crucial, and finer, cultural differentiations and gradations. In fact, we especially risk emptying the category of Hellenism so that it is used in an extremely general and superfluous manner, as a floating signifier; thereby, it no longer comes to mean anything to designate one form of Judaism as being of a particularly Hellenistic nature. Perhaps there is a more theoretically appropriate manner of conceptualizing the relationship between cultural entities by which we shall, at one and the same time, be able to steer past the Scylla that turns Paul’s Judaism and Hellenism into a binary choice and the Charybdis that makes the two of such a comprehensive nature that the differentiation between them loses its value. I concur with the astute observation of Erich Gruen when he endorses the view that:

We avoid the notion of a zero-sum contest in which every gain for Hellenism was a loss for Judaism or vice-versa. The prevailing culture of the Mediterranean could hardly be ignored or dismissed. But adaptation to it need not require compromise of Jewish precepts or practices… Ambiguity adheres to the term “Hellenism” itself. No pure strain of Greek culture, whatever that might be even in principle, confronted the Jews of Palestine or the Diaspora. Transplanted Greek communities mingled with ancient Phoenician traditions on the Levantine coast, with powerful Egyptian elements in Alexandria, with enduring Mesopotamian institutions in Babylon, and with a complex mixture of societies in Asia Minor. The Greek culture with which Jews came into contact comprised a mongrel entity−or rather entities with a different blend in each location of the Mediterranean. The convenient term “Hellenistic” employed here signifies complex amalgamation in the Near East in which the Greek ingredient was a conspicuous presence rather than a monopoly.

Second, I will attempt to sketch a taxonomy that will enable us not only to distinguish between different analytical levels, but also—and perhaps more importantly—to enhance our awareness of the analytical levels at which we, in a particular study, may operate with the Hellenism/Judaism distinction. I think there are different levels of analysis to which this conceptual scheme may advantageously be applied, but it is important also to acknowledge the particular level at which one is working in a specific study of Paul’s respective Judaism and Hellenism, whereby I do not mean to say, obviously, that one is excluded from operating simultaneously with different aspects as long as the pertinent levels are made theoretically and methodologically lucid.

Third, in continuity with recent work in the field of the study of religion, I suggest that it may be advantageous to extend the debate of Paul’s Judaism and Hellenism to a level of analysis that, for a long period of time, has been neglected in the humanities and the social sciences: that is, that of cultural evolution. Needless to say, I acknowledge the contentious nature of this form of thinking, but I nevertheless find it imperative—for reasons that will hopefully become clear—to revitalize a manner of thinking that has been banned for almost a century. Evolutionary reasoning had its heyday from the Enlightenment to around 1920, when the experience of World War I made it intellectually impossible to uphold a form of thinking that had turned Western culture into the apex of civilization and Christianity into the zenith of the history of religion. Although there was a horrendous political aftermath of this type of thinking with the rise of the extreme right-wing political movements of the 1930s, it is fair to say that in intellectual circles, this form of reasoning came to a halt around 1920. In retrospect, though, we may have thrown the baby out with the bathwater: it may be useful to stop neglecting the evolutionary perspective and the scope of questions implied by it and to apply it to the field of problems pertaining to the relationship between Hellenism and Judaism in Paul’s thought world. For this reason, I shall—despite potential problems in taking it up again—argue that we may benefit considerably from the evolutionary perspective when, for instance, we focus on the Hellenism/Judaism field of problems. In fact, the application of this perspective may—in line with my previous point—enable us to refine our discussion of the set of problems involved. However, it ...