The struggle for power—and the violence that accompanies it—has always accompanied the formation of civilizations and their hierarchies. Who has the right to rule? What qualities and characteristics legitimize claims to authority? How do populations respond to their leaders, and at what point does the will of the leader misalign with the needs of the people? Perhaps most importantly, how are efforts to answer those questions remembered and preserved for future generations to consult to avoid similar conflicts and problems? The book of Samuel is the Bible’s great testament to those questions, detailing how Israel transitioned from a turbulent tribal league into a monarchy, but one plagued by competition, duplicity, brutality, and uncertainty. The events in the book build upon the repercussions of that which precedes it until a single ruler—David—assumes the role of king and custodian of Israel’s welfare. But a careful reading reveals a complex tale that offers a potent commentary on the dangers of power, the cost of corruption, the need for redemption, and the demands of justice both human and divine.

1.1. How to Approach the Study of the Book of Samuel

The book of Samuel holds together very well as a single storyline; it purports to tell the story of the rise of kingship in Israel and the major figures of the era who stood behind this change in Israelite political society, and it does this with great literary economy. But as we will see, this carefully wrought story is woven together from an assortment of shorter stories (and other sources) that were originally conceived for different purposes. The creation of the book from these different sources tells us that what we currently read is the end result of much revision, expansion, editing and orchestration at the hands of many authors. These authors—all of whom were trained and skilled ancient scribes—represented diverse social agendas and came from vastly different corners of Israelite society. For example, we will see below that some chapters dealing with the character of Samuel derive from a group of priests who saw Samuel as their great leader/founder and who sought to emphasize his importance to wider audiences at a time when various priestly traditions were in conflict. It is only a later scribal author/editor who took these chapters and worked them into a story about the royal conflict between Saul and David, Israel’s first kings, and it is later still that the Deuteronomists reshaped all of this material with an eye to national history.

While one cannot deny that the end result of all of this scribal activity is a literary masterpiece, we will study this masterpiece by looking at how its component parts interact, as well as how they originated. It is important to see the sources behind the book of Samuel in their own light, which illuminates much about the complicated religious and social networks in ancient Israel as well as how the scribes remembered them. A source that was composed to bolster Saul’s claims to power or criticize David’s policies not only provides information about Saul and David but about how the author of the source understood or remembered each figure. What is more, it reveals what the author felt would be felt most strongly by the audience of his work: their values, fears, needs, and hopes regarding their leaders and the future of their communities. The story told in the book of Samuel is therefore the story of many factions and parties in Israel’s society over many generations, at least as seen from the vantage point of the authors of its contents. Their compositions (and combination of earlier compositions) tell many stories at once, and we will approach these texts with an eye to how they navigate difficult and elusive memories in a way that their early audiences found meaningful.

1.2. The Name of the Book

A clue to the scope and nature of the book’s vision may be found in the fact that in the Hebrew tradition, it is ultimately not named after David but after Samuel (sefer shemu’el), a priestly-prophetic figure who is credited with shepherding Israel into the monarchic era. It is Samuel who galvanizes the nation and reaffirms its covenantal character (1 Samuel 7), and it is he who establishes the book’s ideological genotype as its narrative moves to other figures of national significance (1 Samuel 8, 12, 15). Samuel is thus emblematic of the pre-monarchic institutions that the book of Samuel places in a different category than the institutions and ideologies of kingship. The narrative within the book of Samuel shows a people unified by the rise of a monarchy but also torn apart by it. Had the book primarily functioned as royal propaganda (though its sources may have functioned this way), such tensions would never have survived into its pages. Saul, David and other figures who claim power over Israel all stand in the shadow of the priestly-prophetic figure Samuel, and the book implicitly aligns itself with Samuel’s own sacral authority as it engages in its critique of these other characters and their actions. The later canonizers of the Hebrew Scriptures recognized this and titled the book after the character whose own ambivalence toward kingship resonates throughout the rest of the story. Yet the Septuagint preserves a different name—Basileiōn, or “[1—2] Reigns”—indicating the awareness that the work’s place in the canon was intimately bound to the concept of kingship, both human and divine.

The book of Samuel, then, provides a valuable window into how ancient Israelite scribes conceived of the past. The shapers of the book of Samuel neither attempted to idealize the era that saw the rise of kingship nor did they attempted to vilify it—even if the sources they inherited were conceived for such purposes (see section 2.2 below). Rather, the book of Samuel is a testament to difference and debate about the nature of leadership and power, pluriform in its presentation of ancient Israel’s traditions from a variety of perspectives with a wide spectrum of responses and conclusions. No one perspective is left without some form of counter-argument witnessed within the text; just as the reader encounters the closure of any given episode, the problems it engenders surface and pull the reader deeper into the conflict facing the characters therein. If the book of Samuel looks back upon the birth of monarchic Israel, it values both the infancy of that society as well as the birth pangs that accompanied its arrival onto the stage of history.

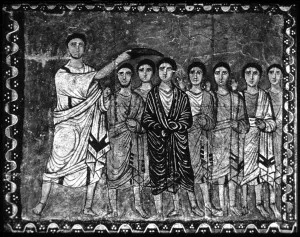

Figure 4.1: The prophet Samuel anoints David in the company of his brothers; fresco from the third-century synagogue at Dura Europos.

2.1. The Style of the Narrative

Some of the Hebrew Scriptures contain intricate, difficult language that requires a good deal of effort to “unpack,” but the book of Samuel generally does not. There are passages and words that demand careful attention and carry more than one dimension of meaning, but the literary style of the book is both fairly unencumbered and quite consistent. Most of the work utilizes an “oral” form of storytelling—that is, its style reflects a culture where narratives (even extensive and intricate ones) were performed and heard in oral contexts, with very lean, simple and direct types of sentence structures. The scribes responsible for this were very likely capable of constructing much more complicated sorts of texts, but this style is very well suited for a tale of the rise of kingship at a time before literacy became a more frequent fixture in common Israelite culture. It also serves a clear rhetorical purpose, since many tales and traditions of the turbulent early monarchic era must have developed and led to contradictory memories and vies about Israel’s earliest kings and their deeds. A lean and direct type of narrative clarifies matters, establishing an “official” version of events but also providing an ostensibly clearer understanding of how and why various traditions and perceptions may have emerged.

Sidebar 4.1: Literary Style and Biblical Narrative

A diversity of literary styles is evident when we examine biblical narratives in some detail. The “simple” style has a sentence structure that is clear, concise, and similar to the way oral performances would convey narrative content. By contrast, other biblical narratives are written in a “dense” style—with complicated clauses and extended strings of nouns and adjectives characterizing the communication of information. While some scholars view this distinction in literary style as an indication of date, others prefer to see it as an indication of the author’s or audience’s social context. A “simple” style might be used in a narrative meant to appeal to rural audiences steeped in oral culture, whereas a “dense” style might be used to highlight the learned, elite character of the text’s contents or authorship.

We should note, however, that these otherwise lean and clear narratives are punctuated with various poetic works at different points (1 Sam. 2:1–10; 2 Samuel 1; 2 Samuel 22, etc.). Poetry is a very different literary genre than narrative prose; scholars often understand it as drawn from other contexts such as public ceremonies or ritual settings and deposited in a narrative framework for different reasons. We see this elsewhere in the Hebrew Scriptures (most notably in Exodus 15 and Judges 5), where not only is the poem given a new meaning by virtue of its new literary function but the narrative surrounding it is infused with greater meaning as well, especially if the poem carried important symbolic attributes before its inclusion into the narrative. The various authors of the book of Samuel engage in this same process, working old poems into the extensive narrative to both suggest the social authenticity of the narrative and to co-opt the way in which those poems were to function or be perceived by subsequent audiences. The simple, lean style of the narrative thus masks a very sophisticated strategy of ideas operating within its verses.

2.2. Sources and Redaction

There can be little doubt that the book of Samuel is indeed a compendium of vastly different sources stemming from disparate social and religious groups. Most scholars see its primary form as deriving from the hands of the Deuteronomistic scribes of the late-seventh to mid-sixth centuries bce; in some cases their redaction incursions are quite obvious. But there is evidence of substantial narrative units that derive from authors living well before the Deuteronomists began their project. These discrete earlier sources hold the most fascination for many researchers, and may be identified here:

- a “Samuel source” regarding his origins and rise to national prominence (1 Sam. 1—3; 7:2–17)

- an independent narrative regarding the capture and return of the Ark (1 Sam. 4:1—7:1)

- a propagandistic narrative regarding Saul’s battlefield prowess (1 Samuel 11)

- a folkloristic tale regarding Saul’s selection by Samuel (1 Sam. 9:1—10:16)

- a brief counter narrative somewhat critical of Saul (1 Sam. 10:17–27)

- a lengthy narrative regarding David’s rise to power (1 Samuel 16—2 Samuel 5)

- an account of David’s transferring of the Ark to Jerusalem (2 Samuel 6)

- a divine promise for an enduring royal dynasty to David (2 Samuel 7)

- a catalog of David’s royal accomplishments (2 Samuel 8)

- the Bathsheba-Uriah episode (2 Samuel 11—12)

- the “Succession Narrative” (2 Samuel 13—20)

- an appendix of ancient archival material (2 Samuel 21—24)

As we can see, the diversity of these sources is vast, and even within these sources one may sense stages of development. A famous example is again to be found in 1 Samuel 16—17, where varying accounts of David’s introduction to Saul are attested, pointing to a compiler’s attempt to give voice to various tales about their initial encounter. The tale of David’s anointing (1 Sam. 16:1–13) is positioned as an introduction to an older tale where Saul is plagued by an evil spirit and David is brought into the royal court to sooth the troubled king with his skills as a musician and singer (1 Sam. 16:14–23). In this same complex of material we also encounter the well-known tale of David’s slaying of Goliath (1 Samuel 17)—a folktale about David probably adapted from a tale about one of David’s soldiers (2 Sam. 21:19). Yet in 1 Samuel 17, Saul seems never to have met David before the Goliath confrontation (v. 58), despite the tale (1 Sam. 16:14–23) that David becomes part of Saul’s royal court. This suggests that the authors of 1 Samuel 17 created their story independently of 1 Samuel 16; the two were only later redacted together.

Sidebar 4.2: Who Killed Goliath?

We are informed in 2 Sam. 21:1...