- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

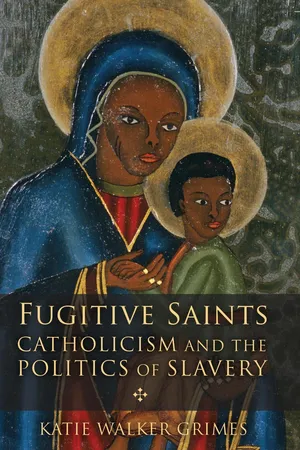

How should the Catholic church remember the sins of its saints? This question proves particularly urgent in the case of those saints who were canonized due to their relation to black slavery. Today, many of their racial virtues seem like racial vices. This book proposes black fugitivity, as both a historical practice and an interpretive principle, to be a strategy by which the church can build new hagiographical habits. Rather than searching inside itself for racial heroes, the church should learn to celebrate those black fugitives who sought refuge outside of it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fugitive Saints by Katie Walker Grimes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

7

Catholic Sainthood and the Afterlife of Slavery

The church’s memory of its racial saints has changed as the church and culture have evolved. More than mere historical figures, saints like Claver and Porres function as historically adaptable symbols of the church’s self-image.[1] The subjective adaptability of the church’s hagiographical memory is not in and of itself bad.[2] But in the case of Claver and Porres, this plasticity has allowed contemporary Catholics to imagine these saints as symbols not of what the church was but of what they wish it had been. Despite the antiracist aspirations of many of their champions, the saintly afterlives of both of these South Americans in fact embody and perpetuate antiblackness supremacy in three primary ways: first, they promote a servile ideology of black gratitude for implicitly white ecclesial saviors; second, they misrepresent the character of racial evil in both the past and the present; and third, they deflect the extent of the church’s corporately vicious participation in antiblackness supremacy. These sainthoods therefore also have limited the church’s capacity to embody corporate racial virtue in the present.

Because Catholics typically have misunderstood slavery, so they have misidentified its afterlife. Just as racialized slavery appears less evil than it actually was when we define it too broadly, so does slavery’s ongoing afterlife. In the afterlife of slavery, antiblackness supremacy attempts to uphold the stigmatizing association between blackness and slave status. Moreover, insofar as the afterlife of slavery structures the world, so it pervades the church—and the church enacts this evil in distinctly Catholic fashion. In particular, the ecclesial afterlife of slavery manifests itself primarily in a perverse attachment to black gratitude; an immoderate fear of black rebellion; an uncritical celebration of interracial proximity, affection, and love; an insatiable desire for white saviors and heroes; and a misplaced desire to elevate white heroes. In order to make this argument, this chapter first provides a brief overview of the history of each saint’s afterlife and then offers a critique. It aims to enhance the church’s capacity to build racial virtue by sharpening its ability to recognize its racial vices.

7.1 Corporate Vindication: Claver and Catholic

Racial Triumphalism

Although Claver was beatified relatively quickly, Vatican officials initially declined to canonize him because of the way he physically abused black slaves. Partially for this reason, his cause languished for nearly a century.[3] But in 1747, Pope Benedict XIV repaired Claver’s reputation when he argued thus:

If we take into careful consideration the obstinate disposition of the Moors, and the savageness of their nature; the contempt exhibited towards his previous warnings [against their improper dances]; his great suavity of manners . . . [in addition to] all those acts of beautiful charity and benevolence towards the Africans, who looked upon him as their father and benefactor . . . [and] the well-known facts that from such blows no asperity of feeling was ever engendered against him . . . no cause for condemnation will be found.[4]

Pope Benedict XIV accepts the logic of slave mastership: Claver beat black slaves because he had to, and they did not mind it anyway. This declaration cleared the way for Pope Pius IX to “approve and accept the several miracles Claver was said to have performed in his lifetime” a little more than a century later, in 1848.[5]

The cause of Claver’s sainthood would gain momentum thereafter. In 1868, shortly after the United States ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, the Jesuit priest Joseph Finotti began to promote Claver’s story for the way it provided “a pattern to those who earnestly and honestly work for the elevation of a down-trodden race” and who “will not allow that a difference in color should be a line of demarcation between souls.” According to Finotti, Claver models “Christian patience and brotherly love,” which he identifies as the “only. . . path that will lead to a sure [racial] triumph.”[6] To this end, Claver purportedly “did for the slaves . . . all the good that they were susceptible of, for the time being.”[7] To African-Americans, Finotti portrayed Claver as an example “of a paternalistic European to whom they should be thankful.”[8] Rather than saving themselves, black people ought to be grateful that they have been saved by whites. Habituated by Africanized slavery and its incipient afterlife, Finotti considers black gratitude to white priestly heroes as a means to racial peace. He urges white people to love black people, but he does not seem to believe they owe black people justice.

A few decades later, Catholic leaders in the United States and Europe began to popularize Claver in order to promote what I term a Catholic racial triumphalism vis-á-vis both Protestantism and Islam.[9] The most significant articulation of the anti-Islamic component of this Claverian Catholic racial triumphalism appears in Pope Leo’s June 1888 encyclical, In Plurimis. The year 1888 was a geopolitically pivotal one: just as the abolition of slavery in Brazil had finally ended black slavery in the Americas, the European imperial scramble for Africa was just beginning. Un-coincidentally canonized in the first month of 1888, Claver was the perfect saint for this year: in addition to evidencing the church’s tireless opposition to slavery, Claver’s sainthood could also be used to sanction the evangelizing mission that would accompany and solidify Europe’s late nineteenth-century colonization of Africa.[10] Claver’s sainthood could in fact present the purported fact of the former as an argument for the moral goodness of latter: European Christians ought to rule black people in Africa because of how well they had ruled them in the Americas. Thus, more than simply commemorating the abolition of black slavery in Brazil, In Plurimis also presented a theological argument for colonizing Africa.

To these ends, Leo argued that the church had always “protected slaves . . . from the savage anger and cruel injuries of their masters.”[11] According to Pope Leo, the Catholic church ultimately has acted as a tireless abolitionist, “cutting out and destroying this dreadful curse of slavery . . . tenderly and with [great] prudence.” Evidencing this, Pope Leo claims that the church denounced and opposed the African slave trade from the moment of its mid-fifteenth-century inception.[12] Pope Leo also identifies the church as an instrument of freedom for the way in which it purportedly has liberated human beings of all races from the most damning form of bondage: enslavement to sin.[13]

Pope Leo does not deny that Catholics owned slaves, whether corporately or as individuals. He instead presents a sanitized history of Christian mastership in which the slavery established by the church fathers differed from its pagan predecessors for the way it uniquely recognized that “the rights of masters extended lawfully indeed over the works of their slaves, but that their power did not extend to using horrible cruelties against their persons.”[14] Articulating an argument that white Catholics in the United States would use against their Protestant counterparts, Pope Leo assures the reader that, unlike the Greeks and Romans before them, these early Christians held slaves not with “cruelty and wickedness” but “great gentleness and humanity.”[15]

Just as Pope Leo claims that Christians helped to protect slaves by holding them captive, so he argues that the church has opposed slavery precisely by making sure it did not end too soon. For Pope Leo, the church has promoted emancipation by resisting abolitionism. Rather than pursuing what he deems “precipitate action in securing the manumission and liberation of the slaves,” the church instead has ensured “that the minds of the slaves should be instructed through her discipline in the Christian faith, and with baptism should acquire habits suitable to the Christian.” To merely emancipate enslaved people without reforming them, he insists, “would have entailed tumults and wrought injury, as well to the slaves themselves as to the commonwealth.”[16] The racially violent theory of freedom that elevated Claver to saintly fame still prevailed more than two hundred years after his beatification: like Claver’s early advocates, Pope Leo believed that the church best liberates enslaved people by ensuring they are enslaved by Christian masters.

Like Claver and his first hagiographers, Pope Leo also identified slave rebellion against Christian masters as not just immoral but unlikely. Strangely overlooking the successful revolution that occurred in French-owned Haiti just a century prior, Pope Leo celebrates the fact that “history has no case to show of Christian slaves for any other cause setting themselves in opposition to their masters of joining in conspiracies against the State.” The church has had a morally salutary effect on enslaved people, convincing them to resist not their bondage, which is lawful, but only “the wicked commands of those above them to the holy law of God.” In helping enslaved people to obey their Christian masters happily, the church has promoted the “fraternal unanimity which should exist between Christians.”[17]

Largely because the Catholic church alone could liberate those black people who had been transported out of Africa, so it retains this power with respect to those women and men who remain there. Just as the Africans who were held as slaves in the Americas had been liberated from enslavement to sin, so modern-day Africans awaited liberation from “Mohammadeans [who deem] Ethiopians and men of similar nations ..... very little superior to brute beasts” and therefore steal them away into a “barbarous” slave trade that transpired not by sea but over land.[18] For Pope Leo, as for Claver, the Middle Passage represented not a trail of terror but a path to true freedom and salvation because it brought purportedly pagan Africans under the power of white Christians. Because the trans-Saharan slave trade, on the other hand, brings black-skinned people under the sway of Muslims, it qualifies as cruel and dehumanizing.

Because it helps “apostolic men . . . find out how best they can secure the safety and liberty of slaves,” Pope Leo praises the “new roads [that] are being made and [the] new commercial enterprises [that are being] undertaken in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table Of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction

- Sainthood and Historical Memory

- Claver’s Ministry for Slaveocracy

- Claver as Race-Making Ally of Antiblackness Supremacy

- The Racialized Humility of Peter Claver

- Coercive Kindness: Reconsidering Claver “from Below”

- The Racialized Humility of Saint Martín de Porres

- Catholic Sainthood and the Afterlife of Slavery

- Venerable Pierre Toussaint and the Search for Fugitive Saints

- Toward a Fugitive Hagiography

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index