Our examination of Ezra-Nehemiah in this chapter will involve a review of the initial return of exiles under the authority of Persia, the career of Ezra, and the “memoir” of Nehemiah.

EZRA-NEHEMIAH

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah were originally counted as one book, under the name of Ezra, and were still regarded as a unit in Hebrew Bibles down through the Middle Ages. In the Greek tradition, they were distinguished as two books from the third century C.E., and in the Latin from the translation of Jerome’s Vulgate in the fourth century. There are several other books associated with the name of Ezra. Most closely related to the canonical books is the apocryphal book of 1 Esdras (sometimes called 3 Ezra). This is a Greek translation of 2 Chronicles 35–36, Ezra 1–10, and Neh 8:1-13, with some differences in the order of material and an additional story about three youths at court, including Zerubbabel, who became governor of Judah after the restoration. It is of interest as a witness to a different arrangement of much of the material in Ezra and Nehemiah. Another apocryphal book, 2 Esdras, contains an important Jewish apocalypse from around 100 C.E. (better known as 4 Ezra), as well as two shorter works of Christian origin, 5 Ezra (2 Esdras 1-2) and 6 Ezra (2 Esdras 15-16). In this chapter, we shall restrict our attention to the canonical books of Ezra and Nehemiah but shall also keep 1 Esdras in mind. Ezra and Nehemiah are two separate books in all modern Bibles, but they are closely bound together and are evidently the work of one author or editor. Accordingly they are often referred to together as Ezra-Nehemiah.

In modern times, the books of Ezra and Nehemiah have often been regarded as part of the Chronicler’s History. The concluding verses of 2 Chronicles (2 Chron 36:22-23) are virtually identical with the opening verses of Ezra (Ezra 1:1-3a). Moreover, there are numerous points of affinity between the language and idiom of Chronicles and that of Ezra-Nehemiah; both show great interest in the temple cult and matters related to it, such as liturgical music and the temple vessels. Some scholars argue that these similarities only reflect the common interests of Second Temple Judaism, and note that there are also differences in terminology. For example, the high priest is called hakkohen haggadol (the great priest) in Ezra-Nehemiah, but hakkohen haro’sh (the head priest) in Chronicles. Those who accept the common authorship of these books respond that the variation in terminology is determined by the context—for example, that Ezra-Nehemiah uses the usual postexilic designation for the high priest while Chronicles uses the older title appropriately for the period of the monarchy. The evidence is not decisive either way. It seems safer to regard Ezra-Nehemiah as an independent composition that has much in common with Chronicles but deals with a distinct period of Jewish history and has its own distinctive concerns.

The content of Ezra-Nehemiah may be outlined as follows.

Ezra 1–6: the return of the exiles and the building of the temple. These events took place more than half a century before the time of Ezra and are reported here on the basis of source documents. The sources include the decree of King Cyrus of Persia authorizing the return (1:2-4, Hebrew; 6:3-5, Aramaic; 5:13-15, Aramaic paraphrase), the list of returnees (2:1-67), and various correspondence with the Persian court (4:7-22; 5:6-17; 6:6-12). All of 4:8—6:18 is in Aramaic, but this section cannot be regarded as a single source. Rather, it seems that the author cited an Aramaic document and then simply continued in Aramaic. We must assume that the author and the intended readership were bilingual. We shall meet a similar phenomenon in the book of Daniel. This section is complicated by the fact that the author groups together related material at the cost of disrupting the historical sequence. At the end of chapter 1, the leader of the Judean community at the time of Cyrus’s decree in 539 B.C.E. is named Sheshbazzar. In chapter 3, the rebuilding of the temple is undertaken by the high priest Joshua and Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel, with no mention of Sheshbazzar. These events can be dated to the reign of King Darius (520 B.C.E.). Yet in 5:16 we are told that Sheshbazzar came and laid the foundations of the temple. In between we find correspondence addressed to King Artaxerxes (486–465) and Darius (522–486). Evidently, the principle governing the composition is thematic rather than chronological. These chapters, which are largely a patchwork of source documents, are invaluable as a source of historical information, but it is clear that they are by no means a simple, straightforward narrative of the events.

The Ezra memoir. The account of the mission of Ezra is found in Ezra 7–10 and continued in Nehemiah 8–9 (actually beginning in Neh 7:73b). This account contains both first and third person narratives. Sources incorporated in this account include the commission of King Artaxerxes to Ezra (Ezra 7:12-26), the list of those who returned with Ezra (8:1-14), and the list of those who had been involved in mixed marriages (10:8-43).

The Nehemiah memoir. The account of the career of Nehemiah is found in the first person account in Neh 1:1—7:73a. Nehemiah 11–13 also pertains to the career of Nehemiah. These chapters include material from various sources, including a first person memoir (e.g., 12:31-43 and 13:4-31).

It is apparent from this summary that Ezra-Nehemiah reports events from three distinct episodes in the first century after the return from the exile: the initial return and rebuilding of the temple, the career of Ezra, and the career of Nehemiah. It is generally believed that these reports were compiled and edited sometime after the mission of Nehemiah, probably around 400 B.C.E.

The tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae, Iran.

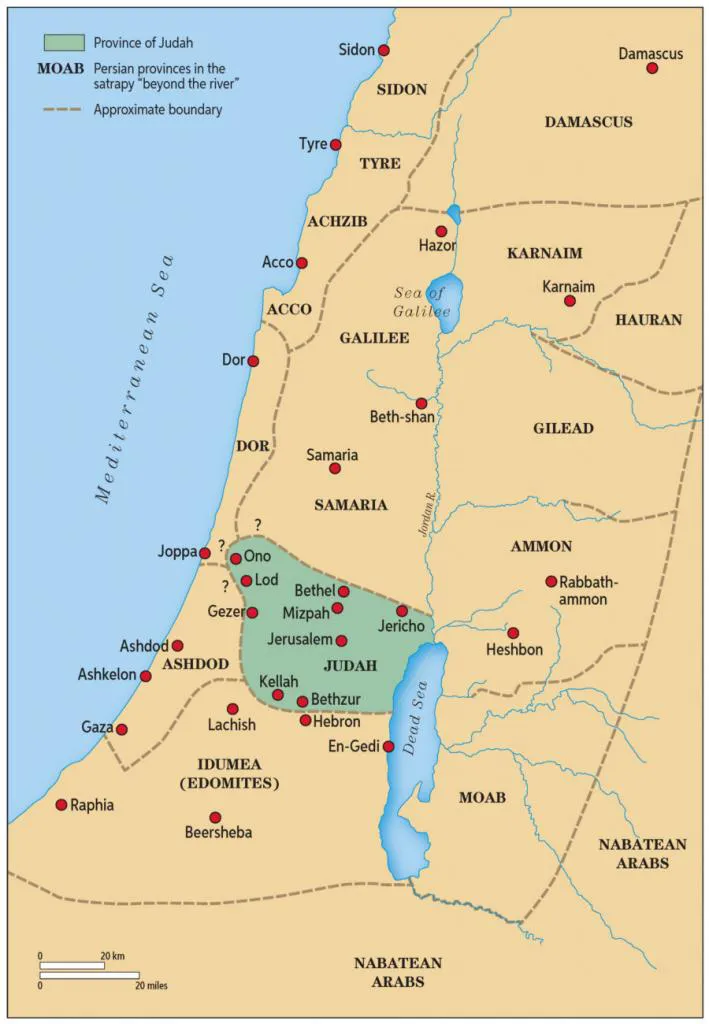

Judah as a Province of the Persian Empire 445–333 B.C.E.

THE INITIAL RETURN

The decree of Cyrus, with which the book of Ezra begins, accords well with what we know of Persian policy toward the conquered peoples. An inscription on a clay barrel known as the Cyrus Cylinder (ANET, 315–16) reflects the way the Persian king presented himself to the people of Babylon. Marduk, god of Babylon, he claimed, had grown angry with the Babylonian king Nabonidus for neglecting his cult, and had summoned Cyrus to set things right. According to the decree in Ezra 1, he told the Judeans that it was “YHWH the God of heaven” who had given him the kingdoms of the earth and had charged him to build the temple in Jerusalem. Some scholars believe that the Hebrew edict in Ezra 1 is the text of a proclamation by a herald; others suspect that it is the composition of the author of Ezra-Nehemiah, based on the Aramaic edict preserved in Ezra 6:3-5. The latter edict says nothing about Cyrus’s indebtedness to YHWH but simply orders that the temple be rebuilt to certain specifications and that the vessels taken by Nebuchadnezzar be restored. The authenticity of the Aramaic edict is not in dispute.

A noteworthy feature of the initial restoration is the designation of Sheshbazzar as “Prince of Judah.” “Prince” (Hebrew nasi’) is the old title for the leader of the tribes in the Priestly strand of the Pentateuch and is also the preferred title for the Davidic ruler in Ezekiel (e.g., Ezek 34:23-24; 37:24-25). The use of this title strongly suggests that Sheshbazzar was descended from the line of David and so was a potential heir to the throne. His name does not appear in the genealogies of Chronicles, however. He has sometimes been identified with Shenazzar, who is listed as a son of Jeconiah, the exiled king of Judah, in 1 Chron 3:18. The names are different, but the suspicion that Sheshbazzar must have been a Davidide remains. Zerubbabel, who appears to have succeeded Sheshbazzar as governor of Judah, is listed as a grandson of Jeconiah in 1 Chron 3:19, but as son of Pedaiah rather than of Shealtiel as in the books of Ezra and Haggai. Interestingly enough, Ezra draws no attention to Zerubbabel’s Davidic ancestry. The editors of Ezra-Nehemiah were loyal Persian subjects with no sympathy for messianic dreams. The predominance of priests and Levites in the list of returned exiles presumably reflects the historical reality but also reflects the priestly orientation of the author or editor, which is similar to that of Chronicles.

Sheshbazzar disappears quickly and silently from the stage of history. According to Ezra 5:16, it was he who laid the foundation of the temple. Yet in Ezra 3 it is Joshua and Zerubbabel who take the lead in rebuilding the temple, and the book of Zechariah explicitly credits Zerubbabel with laying the foundation (Zech 4:9). Zerubbabel’s activity was in the reign of Darius, nearly two decades after the return. The book of Ezra, however, obscures the lapse of time. The uncritical reader most readily supposes that the “seventh month” of Ezra 3:1, when Joshua and Zerubbabel build the altar, is in the year of the initial return. Similarly Ezra 3:8 says that Zerubbabel and Joshua laid the foundation “in the second year after their return.” If this is true, however, then Joshua and Zerubbabel must have been part of a second return some eighteen years after the initial one. The description of the mixed reaction of the people when they saw the foundation of the new temple (Ezra 3:12-13) is paralleled in Hag 2:3, which also notes that some people were disappointed with its reduced size.

The account in Ezra obscures the fact that there was a lapse of approximately twenty years between the initial return and the eventual building of the temple. The book of Haggai explains this delay by suggesting that people were more concerned to build their own houses than to rebuild the temple. In the book of Ezra, any delay in the rebuilding is explained by the opposition of “the adversaries of Judah” (4:1). These people offered to join in the building, “for we worship your God as you do, and we have been sacrificing to him ever since the days of King Esarhaddon of Assyria who brought us here.” The implication is that the people who were in the land when the exiles returned were the descendants of the settlers brought to northern Israel by the Assyrians (2 Kgs 17:24; the king is identified in the context as Shalmaneser). It is indeed likely that the people of Samaria, who had their own governor, hoped to exercise influence over Jerusalem. But there must also have been some people who were native Judeans who had not been deported and who expected, reasonably enough, to be included in the community around the Second Temple. The leaders of the exiles, however, took a strictly exclusivist position: “But Zerubbabel, Jeshua, and the rest of the heads of families in Israel said to them, ‘You shall have no part with us in building a house to our God; but we alone will build to the Lord, the God of Israel, as King Cyrus of Persia has commanded us’ ” (Ezra 4:3). The exiles evidently regarded themselves as a pure community, which should not be mingled with “the people of the land.” This rejection of cooperation, even from fellow Yahwists, was a fateful decision, and set the stage for centuries of tensions between the Jewish community that was centered on the temple and its neighbors.

The correspondence cited to show the opposition to the returnees is out of chronological order. The letter in Ezra 4:11-22 is addressed to King Artaxerxes (probably Artaxerxes I, 465–424 B.C.E.) and is concerned with the rebuilding of the city walls, not with the temple. The city walls were the great preoccupation of Nehemiah, who was active in Jerusalem in the reign of Artaxerxes. This document is inserted into the account of the building of the temple to explain the delay in the construction. According to Ezra 4:17-22, the king ordered that the work be stopped. In contrast, the second letter, in 5:6-17, is addressed to Darius and concerns the rebuilding of the temple. Ezra 6 records the response of Darius, authorizing the continuation of the building of the temple. The impression is given that the Persian authorities vacillated, whether through indecision or simply through bureaucratic incompetence. If the letter to Artaxerxes is restored to its proper context, however, there is no indecision on the part of the Persians with regard to the temple. The rebuilding had been authorized, and the objections were overruled. We shall return to the question of the walls when we discuss the career of Nehemiah.

THE C...