- 469 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

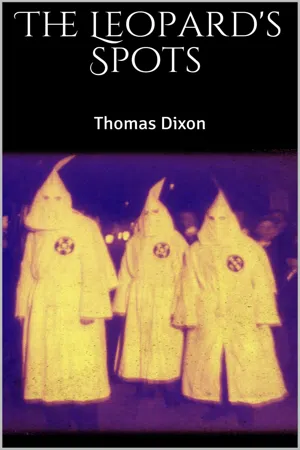

The Leopard's Spots

About this book

ON the field of Appomattox General Lee was waiting the return of a courier. His handsome face was clouded by the deepening shadows of defeat. Rumours of surrender had spread like wildfire, and the ranks of his once invincible army were breaking into chaos. Suddenly the measured tread of a brigade was heard marching into action, every movement quick with the perfect discipline, the fire, and the passion of the first days of the triumphant Confederacy. "What brigade is that?" he sharply asked. "Cox's North Carolina, " an aid replied. As the troops swept steadily past the General, his eyes filled with tears, he lifted his hat, and exclaimed, "God bless old North Carolina!"

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I—A HERO RETURNS

O N the field of Appomattox General Lee was waiting the return of a courier. His handsome face was clouded by the deepening shadows of defeat. Rumours of surrender had spread like wildfire, and the ranks of his once invincible army were breaking into chaos.

Suddenly the measured tread of a brigade was heard marching into action, every movement quick with the perfect discipline, the fire, and the passion of the first days of the triumphant Confederacy.

“ What brigade is that?” he sharply asked.

“ Cox’s North Carolina,” an aid replied.

As the troops swept steadily past the General, his eyes filled with tears, he lifted his hat, and exclaimed, “God bless old North Carolina!”

The display of matchless discipline perhaps recalled to the great commander that awful day of Gettysburg when the Twenty-sixth North Carolina infantry had charged with 820 men rank and file and left 704 dead and wounded on the ground that night. Company F from Campbell county charged with 91 men and lost every man killed and wounded. Fourteen times their colours were shot down, and fourteen times raised again. The last time they fell from the hands of gallant Colonel Harry Burgwyn, twenty-one years old, commander of the regiment, who seized them and was holding them aloft when instantly killed.

The last act of the tragedy had closed. Johnston surrendered to Sherman at Greensboro on April 26th, 1865, and the Civil War ended,—the bloodiest, most destructive war the world ever saw. The earth had been baptized in the blood of five hundred thousand heroic soldiers, and a new map of the world had been made.

The ragged troops were straggling home from Greensboro and Appomattox along the country roads. There were no mails, telegraph lines or railroads. The men were telling the story of the surrender. White-faced women dressed in coarse homespun met them at their doors and with quivering lips heard the news.

Surrender!

A new word in the vocabulary of the South—a word so terrible in its meaning that the date of its birth was to be the landmark of time. Henceforth all events would be reckoned from this; “before the Surrender,” or “after the Surrender.”

Desolation everywhere marked the end of an era. Not a cow, a sheep, a horse, a fowl, or a sign of animal life save here and there a stray dog, to be seen. Grim chimneys marked the site of once fair homes. Hedgerows of tangled blackberry briar and bushes showed where a fence had stood before war breathed upon the land with its breath of fire and harrowed it with teeth of steel.

These tramping soldiers looked worn and dispirited. Their shoulders stooped, they were dirty and hungry. They looked worse than they felt, and they felt that the end of the world had come.

They had answered those awful commands to charge without a murmur; and then, rolled back upon a sea of blood, they charged again over the dead bodies of their comrades. When repulsed the second time and the mad cry for a third charge from some desperate commander had rung over the field, still without a word they pulled their old ragged hats down close over their eyes as though to shut out the hail of bullets, and, through level sheets of blinding flame, walked straight into the jaws of hell. This had been easy. Now their feet seemed to falter as though they were not sure of the road.

In every one of these soldier’s hearts, and over all the earth hung the shadow of the freed Negro, transformed by the exigency of war from a Chattel to be bought and sold into a possible Beast to be feared and guarded. Around this dusky figure every white man’s soul was keeping its grim vigil.

North Carolina, the typical American Democracy, had loved peace and sought in vain to stand between the mad passions of the Cavalier of the South and the Puritan fanatic of the North. She entered the war at last with a sorrowful heart but a soul clear in the sense of tragic duty. She sent more boys to the front than any other state of the Confederacy—and left more dead on the field. She made the last charge and fired the last volley for Lee’s army at Appomattox.

These were the ragged country boys who were slowly tramping homeward. The group whose fortunes we are to follow were marching toward the little village of Hambright that nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge under the shadows of King’s Mountain. They were the sons of the men who had first declared their independence of Great Britain in America and had made their country a hornet’s nest for Lord Cornwallis in the darkest days of the cause of Liberty. What tongue can tell the tragic story of their humble home coming?

In rich Northern cities could be heard the boom of guns, the scream of steam whistles, the shouts of surging hosts greeting returning regiments crowned with victory. From every flag-staff fluttered proudly the flag that our fathers had lifted in the sky—the flag that had never met defeat.

It is little wonder that in this hour of triumph the world should forget the defeated soldiers who without a dollar in their pockets were tramping to their ruined homes.

Yet Nature did not seem to know of sorrow or death. Birds were singing their love songs from the hedgerows, the fields were clothed in gorgeous robes of wild flowers beneath which forget-me-nots spread their contrasting hues of blue, while life was busy in bud and starting leaf reclothing the blood-stained earth in radiant beauty.

As the sun was setting behind the peaks of the Blue Ridge, a giant negro entered the village of Ham-bright. He walked rapidly down one of the principal streets, passed the court house square unobserved in the gathering twilight, and three blocks further along paused before a law-office that stood in the corner of a beautiful lawn filled with shrubbery and flowers.

“ Dars de ole home, praise de Lawd! En now I’se erfeard ter see my Missy, en tell her Marse Charles’s daid. Hit’ll kill her! Lawd hab mussy on my po black soul! How kin I!”

He walked softly up the alley that led toward the kitchen past the “big” house, which after all was a modest cottage boarded up and down with weatherstrips nestling amid a labyrinth of climbing roses, honeysuckles, fruit bearing shrubbery and balsam trees. The negro had no difficulty in concealing his movements as he passed.

“ Lordy, dars Missy watchin’ at de winder! How pale she look! En she wuz de purties’ bride in de two counties! God-der-mighty, I mus’ git somebody ter he’p me! I nebber tell her! She drap daid right ’fore my eyes, en liant me twell I die. I run fetch de Preacher, Marse John Durham, he kin tell her.”

A few moments later he was knocking at the door of the parsonage of the Baptist church.

“ Nelse! At last! I knew you’d come!”

“ Yassir, Marse John, I’se home. Hit’s me.”

“ And your Master is dead. I was sure of it, but I never dared tell your Mistress. You came for me to help you tell her. People said you had gone over into the promised land of freedom and forgotten your people; but Nelse, I never believed it of you and I’m doubly glad to shake your hand to-night because you’ve brought a brave message from heroic lips and because you have brought a braver message in your honest black face of faith and duty and life and love.”

“ Thankee Marse John, I wuz erbleeged ter come home.”

The Preacher stepped into the hall and called the servant from the kitchen.

“ Aunt Mary, when your Mistress returns tell her I’ve received an urgent call and will not be at home for supper.”

“ I’ll be ready in a minute, Nelse,” he said, as he disappeared into the study. When he reached his desk, he paused and looked about the room in a helpless way as though trying to find some half forgotten volume in the rows of books that lined the walls and lay in piles on his desk and tables. He knelt beside the desk and prayed. When he rose there was a soft light in his eyes that were half filled with tears.

Standing in the dim light of his study he was a striking man. He had a powerful figure of medium height, deep piercing eyes and a high intellectual forehead. His hair was black and thick. He was a man of culture, had graduated at the head of his class at Wake Forest College before the war, and was a profound student of men and books. He was now thirty-five years old and the acknowledged leader of the Baptist denomination in the state. He was eloquent, witty, and proverbially good natured. His voice in the pulpit was soft and clear, and full of a magnetic quality that gave him hypnotic power over an audience. He had the prophetic temperament and was more of poet than theologian.

The people of this village were proud of the man as a citizen and loved him passionately as their preacher. Great churches had called him, but he had never accepted. There was in his make-up an element of the missionary that gave his personality a peculiar force.

He had been the college mate of Colonel Charles Gaston whose faithful slave had come to him for help, and they had always been bosom friends. He had performed the marriage ceremony for the Colonel ten years before when he had led to the altar the beautiful daughter of the richest planter in the adjoining county. Durham’s own heart was profoundly moved by his friend’s happiness and he threw into the brief preliminary address so much of tenderness and earnest passion that the trembling bride and groom forgot their fright and were melted to tears. Thus began an association of their family life that was closer than their college days.

He closed his lips firmly for an instant, softly shut the door and was soon on the way with Nelse. On reaching the house, Nelse went directly to the kitchen, while the Preacher walking along the circular drive approached the front. His foot had scarcely touched the step when Mrs. Gaston opened the door.

“ Oh, Dr. Durham, I am so glad you have come!” she exclaimed. “I’ve been depressed to-day, watching the soldiers go by. All day long the poor foot-sore fellows have been passing. I stopped some of them to ask about Colonel Gaston and I thought one of them knew something and would not tell me. I brought him in and gave him dinner, and tried to coax him, but he only looked wistfully at me, stammered and said he didn’t know. But some how I feel that he did. Come in Doctor, and say something to cheer me. If I only had your faith in God!”

“ I have need of it all to-night, Madam!” he answered with bowed head.

“ Then you have heard bad news?”

“ I have heard news,—wonderful news of faith and love, of heroism and knightly valour, that will be a priceless heritage to you and yours. Nelse has returned—”

“ God have mercy on me!”—she gasped covering her face and raising her arm as though cowering from a mortal blow.

“ Here is Nelse, Madam. Hear his story. He has only told me a word or two.” Nelse had slipped quietly in the back door.

“ Yassum. Missy, I’se home at las’.”

She looked at him strangely for a moment. “Nelse, I’ve dreamed and dreamed of your coming, but always with him. And now you come alone to tell me he is dead. Lord have pity! there is nothing left!” There was a far-away sound in her voice as though half dreaming.

“ Yas, Missy, dey is, I jes seed him—my young Marster—dem bright eyes, de ve’y nose, de chin, de mouf! He walks des like Marse Charles, he talks like him, he de ve’y spit er him, en how he hez growed! He’ll be er man fo you knows it. En I’se got er letter fum his Pa fur him, an er letter fur you, Missy.”

At this moment Charlie entered the room, slipped past Nelse and climbed into his mother’s arms. He was a sturdy little fellow of eight years with big brown eyes and sensitive mouth.

“ Yassir—Ole Grant wuz er pushin’ us dar afo’ Richmond Pear ter me lak Marse Robert been er fightin’ him ev’y day for six monts. But he des keep on pushin’ en pushin’ us. Marse Charles say ter me one night atter I been playin’ de banjer fur de boys, Come ter my tent Nelse fo turnin’ in—I wants ter see you.’ He talk so solemn like, I cut de banjer short, en go right er long wid him. He been er writin’ en done had two letters writ. He say, ‘Nelse, we gwine ter git outen dese trenches ter-morrer. It twell be my las’ charge. I feel it. Ef I falls, you take my swode, en watch en dese letters back home to your Mist’ess and young Marster, en you promise me, boy, to stan’ by em in life ez I stan’ by you.’ He know I lub him bettern any body in dis work, en dat I’d rudder be his slave dan be free if he’s daid! En I say, ‘Dat I will, Marse Charles.’

“ De nex day we up en charge ole Grant. Pears ter me I nebber see so many dead Yankees on dis yearth ez we see layin’ on de groun’ whar we brake froo dem lines! But dey des kep fetchin’ up annudder army back er de one we breaks, twell bymeby, dey swing er whole millyon er Yankees right plum behin’ us, en five millyon er fresh uns come er swoopin’ down in front. Den yer otter see my Marster! He des kinder riz in de air—pear ter me like he wuz er foot taller en say to his men—’ ‘Bout face, en charge de line in de rear!’ Wall sar, we cut er hole clean froo dem Yankees en er minute, end den bout face ergin en begin ter walk backerds er fightin’ like wilecats ev’y inch. We git mos back ter de trenches, when Marse Charles drap des lak er flash! I runned up to him en dar wuz er big hole in his breas’ whar er bullet gone clean froo his heart. He nebber groan. I tuk his head up in my arms en cry en take on en call him! I pull back his close en listen at his heart. Hit wuz still. I takes de swode an de watch en de letters outen de pockets en start on—when bress God, yer cum dat whole Yankee army ten hundred millyons, en dey tromple all over us!

“ Den I hear er Yankee say ter me ‘Now, my man, you’se free.’ ‘Yassir, sezzi, dats so,’ en den I see a hole ter run whar dey warn’t no Yankees, en I run spang into er millyon mo. De Yankees wuz ev’y whar. Pear ter me lak dey riz up outer de groun’. All dat day I try ter get away fum ’em. En long ’bout night dey ’rested me en fetch me up fo er Genr’l, en he say, ‘What you tryin’ ter get froo our lines fur, nigger? Doan yer know yer free now, en if you go back you’d be a slave ergin?’”

“ Dats so, sah,” sezzi, “but I’se ’bleeged ter go home.”

“ What fur?” sezze.

“ Promise Marse Charles ter take dese letters en swode en watch back home to my Missus en young Marster, en dey waitin’ fur me—I’se ’bleeged ter go.”

“ Den he tuk de letters en read er minute, en his eyes gin ter water en he choke up en say, ‘Go-long!’

“ Den I skeedaddled ergin. Dey kep on ketchin’ me twell bimeby er nasty stinkin low-life slue-footed Yankee kotched me en say dat I wuz er dang’us nigger, en sont me wid er lot er our prisoners way up ter ole Jonson’s Islan’ whar I mos froze ter deaf. I stay dar twell one day er fine lady what say she from Boston cum er long, en I up en tells her all erbout Marse Charles and my Missus, en how dey all waitin’ fur me, en how bad I want ter go home, en de nex news I knowed I wuz on er train er whizzin’ down home wid my way all paid. I get wid our men at Greensboro en come right on fas’ ez my legs’d carry me.”

There was silence for a moment and then slowly Mrs. Gaston said, “May God reward you, Nelse!”

“ Yassum, I’se free, Missy, but I gwine ter wuk for you en my young Marster.”

Mrs. Gaston had lived daily in a sort of trance through those four years of war, dreaming and planning for the great day when her lover would return a handsome bronzed and famous man. She had never conceived of the possibility of a world without his will and love to lean upon. The Preacher was both puzzled and alarmed by the strangely calm manner she now assumed. Before leaving the home he cautioned Aunt Eve to watch her Mistress closely and send for him if anything happened.

When the boy was asleep in the nursery adjoining her room, she quietly closed the door, took the sword of her dead lover-husband in her lap and looked long and tend...

Suddenly the measured tread of a brigade was heard marching into action, every movement quick with the perfect discipline, the fire, and the passion of the first days of the triumphant Confederacy.

“ What brigade is that?” he sharply asked.

“ Cox’s North Carolina,” an aid replied.

As the troops swept steadily past the General, his eyes filled with tears, he lifted his hat, and exclaimed, “God bless old North Carolina!”

The display of matchless discipline perhaps recalled to the great commander that awful day of Gettysburg when the Twenty-sixth North Carolina infantry had charged with 820 men rank and file and left 704 dead and wounded on the ground that night. Company F from Campbell county charged with 91 men and lost every man killed and wounded. Fourteen times their colours were shot down, and fourteen times raised again. The last time they fell from the hands of gallant Colonel Harry Burgwyn, twenty-one years old, commander of the regiment, who seized them and was holding them aloft when instantly killed.

The last act of the tragedy had closed. Johnston surrendered to Sherman at Greensboro on April 26th, 1865, and the Civil War ended,—the bloodiest, most destructive war the world ever saw. The earth had been baptized in the blood of five hundred thousand heroic soldiers, and a new map of the world had been made.

The ragged troops were straggling home from Greensboro and Appomattox along the country roads. There were no mails, telegraph lines or railroads. The men were telling the story of the surrender. White-faced women dressed in coarse homespun met them at their doors and with quivering lips heard the news.

Surrender!

A new word in the vocabulary of the South—a word so terrible in its meaning that the date of its birth was to be the landmark of time. Henceforth all events would be reckoned from this; “before the Surrender,” or “after the Surrender.”

Desolation everywhere marked the end of an era. Not a cow, a sheep, a horse, a fowl, or a sign of animal life save here and there a stray dog, to be seen. Grim chimneys marked the site of once fair homes. Hedgerows of tangled blackberry briar and bushes showed where a fence had stood before war breathed upon the land with its breath of fire and harrowed it with teeth of steel.

These tramping soldiers looked worn and dispirited. Their shoulders stooped, they were dirty and hungry. They looked worse than they felt, and they felt that the end of the world had come.

They had answered those awful commands to charge without a murmur; and then, rolled back upon a sea of blood, they charged again over the dead bodies of their comrades. When repulsed the second time and the mad cry for a third charge from some desperate commander had rung over the field, still without a word they pulled their old ragged hats down close over their eyes as though to shut out the hail of bullets, and, through level sheets of blinding flame, walked straight into the jaws of hell. This had been easy. Now their feet seemed to falter as though they were not sure of the road.

In every one of these soldier’s hearts, and over all the earth hung the shadow of the freed Negro, transformed by the exigency of war from a Chattel to be bought and sold into a possible Beast to be feared and guarded. Around this dusky figure every white man’s soul was keeping its grim vigil.

North Carolina, the typical American Democracy, had loved peace and sought in vain to stand between the mad passions of the Cavalier of the South and the Puritan fanatic of the North. She entered the war at last with a sorrowful heart but a soul clear in the sense of tragic duty. She sent more boys to the front than any other state of the Confederacy—and left more dead on the field. She made the last charge and fired the last volley for Lee’s army at Appomattox.

These were the ragged country boys who were slowly tramping homeward. The group whose fortunes we are to follow were marching toward the little village of Hambright that nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge under the shadows of King’s Mountain. They were the sons of the men who had first declared their independence of Great Britain in America and had made their country a hornet’s nest for Lord Cornwallis in the darkest days of the cause of Liberty. What tongue can tell the tragic story of their humble home coming?

In rich Northern cities could be heard the boom of guns, the scream of steam whistles, the shouts of surging hosts greeting returning regiments crowned with victory. From every flag-staff fluttered proudly the flag that our fathers had lifted in the sky—the flag that had never met defeat.

It is little wonder that in this hour of triumph the world should forget the defeated soldiers who without a dollar in their pockets were tramping to their ruined homes.

Yet Nature did not seem to know of sorrow or death. Birds were singing their love songs from the hedgerows, the fields were clothed in gorgeous robes of wild flowers beneath which forget-me-nots spread their contrasting hues of blue, while life was busy in bud and starting leaf reclothing the blood-stained earth in radiant beauty.

As the sun was setting behind the peaks of the Blue Ridge, a giant negro entered the village of Ham-bright. He walked rapidly down one of the principal streets, passed the court house square unobserved in the gathering twilight, and three blocks further along paused before a law-office that stood in the corner of a beautiful lawn filled with shrubbery and flowers.

“ Dars de ole home, praise de Lawd! En now I’se erfeard ter see my Missy, en tell her Marse Charles’s daid. Hit’ll kill her! Lawd hab mussy on my po black soul! How kin I!”

He walked softly up the alley that led toward the kitchen past the “big” house, which after all was a modest cottage boarded up and down with weatherstrips nestling amid a labyrinth of climbing roses, honeysuckles, fruit bearing shrubbery and balsam trees. The negro had no difficulty in concealing his movements as he passed.

“ Lordy, dars Missy watchin’ at de winder! How pale she look! En she wuz de purties’ bride in de two counties! God-der-mighty, I mus’ git somebody ter he’p me! I nebber tell her! She drap daid right ’fore my eyes, en liant me twell I die. I run fetch de Preacher, Marse John Durham, he kin tell her.”

A few moments later he was knocking at the door of the parsonage of the Baptist church.

“ Nelse! At last! I knew you’d come!”

“ Yassir, Marse John, I’se home. Hit’s me.”

“ And your Master is dead. I was sure of it, but I never dared tell your Mistress. You came for me to help you tell her. People said you had gone over into the promised land of freedom and forgotten your people; but Nelse, I never believed it of you and I’m doubly glad to shake your hand to-night because you’ve brought a brave message from heroic lips and because you have brought a braver message in your honest black face of faith and duty and life and love.”

“ Thankee Marse John, I wuz erbleeged ter come home.”

The Preacher stepped into the hall and called the servant from the kitchen.

“ Aunt Mary, when your Mistress returns tell her I’ve received an urgent call and will not be at home for supper.”

“ I’ll be ready in a minute, Nelse,” he said, as he disappeared into the study. When he reached his desk, he paused and looked about the room in a helpless way as though trying to find some half forgotten volume in the rows of books that lined the walls and lay in piles on his desk and tables. He knelt beside the desk and prayed. When he rose there was a soft light in his eyes that were half filled with tears.

Standing in the dim light of his study he was a striking man. He had a powerful figure of medium height, deep piercing eyes and a high intellectual forehead. His hair was black and thick. He was a man of culture, had graduated at the head of his class at Wake Forest College before the war, and was a profound student of men and books. He was now thirty-five years old and the acknowledged leader of the Baptist denomination in the state. He was eloquent, witty, and proverbially good natured. His voice in the pulpit was soft and clear, and full of a magnetic quality that gave him hypnotic power over an audience. He had the prophetic temperament and was more of poet than theologian.

The people of this village were proud of the man as a citizen and loved him passionately as their preacher. Great churches had called him, but he had never accepted. There was in his make-up an element of the missionary that gave his personality a peculiar force.

He had been the college mate of Colonel Charles Gaston whose faithful slave had come to him for help, and they had always been bosom friends. He had performed the marriage ceremony for the Colonel ten years before when he had led to the altar the beautiful daughter of the richest planter in the adjoining county. Durham’s own heart was profoundly moved by his friend’s happiness and he threw into the brief preliminary address so much of tenderness and earnest passion that the trembling bride and groom forgot their fright and were melted to tears. Thus began an association of their family life that was closer than their college days.

He closed his lips firmly for an instant, softly shut the door and was soon on the way with Nelse. On reaching the house, Nelse went directly to the kitchen, while the Preacher walking along the circular drive approached the front. His foot had scarcely touched the step when Mrs. Gaston opened the door.

“ Oh, Dr. Durham, I am so glad you have come!” she exclaimed. “I’ve been depressed to-day, watching the soldiers go by. All day long the poor foot-sore fellows have been passing. I stopped some of them to ask about Colonel Gaston and I thought one of them knew something and would not tell me. I brought him in and gave him dinner, and tried to coax him, but he only looked wistfully at me, stammered and said he didn’t know. But some how I feel that he did. Come in Doctor, and say something to cheer me. If I only had your faith in God!”

“ I have need of it all to-night, Madam!” he answered with bowed head.

“ Then you have heard bad news?”

“ I have heard news,—wonderful news of faith and love, of heroism and knightly valour, that will be a priceless heritage to you and yours. Nelse has returned—”

“ God have mercy on me!”—she gasped covering her face and raising her arm as though cowering from a mortal blow.

“ Here is Nelse, Madam. Hear his story. He has only told me a word or two.” Nelse had slipped quietly in the back door.

“ Yassum. Missy, I’se home at las’.”

She looked at him strangely for a moment. “Nelse, I’ve dreamed and dreamed of your coming, but always with him. And now you come alone to tell me he is dead. Lord have pity! there is nothing left!” There was a far-away sound in her voice as though half dreaming.

“ Yas, Missy, dey is, I jes seed him—my young Marster—dem bright eyes, de ve’y nose, de chin, de mouf! He walks des like Marse Charles, he talks like him, he de ve’y spit er him, en how he hez growed! He’ll be er man fo you knows it. En I’se got er letter fum his Pa fur him, an er letter fur you, Missy.”

At this moment Charlie entered the room, slipped past Nelse and climbed into his mother’s arms. He was a sturdy little fellow of eight years with big brown eyes and sensitive mouth.

“ Yassir—Ole Grant wuz er pushin’ us dar afo’ Richmond Pear ter me lak Marse Robert been er fightin’ him ev’y day for six monts. But he des keep on pushin’ en pushin’ us. Marse Charles say ter me one night atter I been playin’ de banjer fur de boys, Come ter my tent Nelse fo turnin’ in—I wants ter see you.’ He talk so solemn like, I cut de banjer short, en go right er long wid him. He been er writin’ en done had two letters writ. He say, ‘Nelse, we gwine ter git outen dese trenches ter-morrer. It twell be my las’ charge. I feel it. Ef I falls, you take my swode, en watch en dese letters back home to your Mist’ess and young Marster, en you promise me, boy, to stan’ by em in life ez I stan’ by you.’ He know I lub him bettern any body in dis work, en dat I’d rudder be his slave dan be free if he’s daid! En I say, ‘Dat I will, Marse Charles.’

“ De nex day we up en charge ole Grant. Pears ter me I nebber see so many dead Yankees on dis yearth ez we see layin’ on de groun’ whar we brake froo dem lines! But dey des kep fetchin’ up annudder army back er de one we breaks, twell bymeby, dey swing er whole millyon er Yankees right plum behin’ us, en five millyon er fresh uns come er swoopin’ down in front. Den yer otter see my Marster! He des kinder riz in de air—pear ter me like he wuz er foot taller en say to his men—’ ‘Bout face, en charge de line in de rear!’ Wall sar, we cut er hole clean froo dem Yankees en er minute, end den bout face ergin en begin ter walk backerds er fightin’ like wilecats ev’y inch. We git mos back ter de trenches, when Marse Charles drap des lak er flash! I runned up to him en dar wuz er big hole in his breas’ whar er bullet gone clean froo his heart. He nebber groan. I tuk his head up in my arms en cry en take on en call him! I pull back his close en listen at his heart. Hit wuz still. I takes de swode an de watch en de letters outen de pockets en start on—when bress God, yer cum dat whole Yankee army ten hundred millyons, en dey tromple all over us!

“ Den I hear er Yankee say ter me ‘Now, my man, you’se free.’ ‘Yassir, sezzi, dats so,’ en den I see a hole ter run whar dey warn’t no Yankees, en I run spang into er millyon mo. De Yankees wuz ev’y whar. Pear ter me lak dey riz up outer de groun’. All dat day I try ter get away fum ’em. En long ’bout night dey ’rested me en fetch me up fo er Genr’l, en he say, ‘What you tryin’ ter get froo our lines fur, nigger? Doan yer know yer free now, en if you go back you’d be a slave ergin?’”

“ Dats so, sah,” sezzi, “but I’se ’bleeged ter go home.”

“ What fur?” sezze.

“ Promise Marse Charles ter take dese letters en swode en watch back home to my Missus en young Marster, en dey waitin’ fur me—I’se ’bleeged ter go.”

“ Den he tuk de letters en read er minute, en his eyes gin ter water en he choke up en say, ‘Go-long!’

“ Den I skeedaddled ergin. Dey kep on ketchin’ me twell bimeby er nasty stinkin low-life slue-footed Yankee kotched me en say dat I wuz er dang’us nigger, en sont me wid er lot er our prisoners way up ter ole Jonson’s Islan’ whar I mos froze ter deaf. I stay dar twell one day er fine lady what say she from Boston cum er long, en I up en tells her all erbout Marse Charles and my Missus, en how dey all waitin’ fur me, en how bad I want ter go home, en de nex news I knowed I wuz on er train er whizzin’ down home wid my way all paid. I get wid our men at Greensboro en come right on fas’ ez my legs’d carry me.”

There was silence for a moment and then slowly Mrs. Gaston said, “May God reward you, Nelse!”

“ Yassum, I’se free, Missy, but I gwine ter wuk for you en my young Marster.”

Mrs. Gaston had lived daily in a sort of trance through those four years of war, dreaming and planning for the great day when her lover would return a handsome bronzed and famous man. She had never conceived of the possibility of a world without his will and love to lean upon. The Preacher was both puzzled and alarmed by the strangely calm manner she now assumed. Before leaving the home he cautioned Aunt Eve to watch her Mistress closely and send for him if anything happened.

When the boy was asleep in the nursery adjoining her room, she quietly closed the door, took the sword of her dead lover-husband in her lap and looked long and tend...

Table of contents

- The Leopard's Spots

- LEADING CHARACTERS OF THE STORY

- BOOK ONE—LEGREE’S REGIME

- CHAPTER I—A HERO RETURNS

- CHAPTER II—A LIGHT SHINING IN DARKNESS

- CHAPTER III—DEEPENING SHADOWS

- CHAPTER IV—MR. LINCOLN’S DREAM

- CHAPTER V—THE OLD AND THE NEW CHURCH

- CHAPTER VI—THE PREACHER AND THE WOMAN OF BOSTON

- CHAPTER VII—THE HEART OF A CHILD

- CHAPTER VIII—AN EXPERIMENT IN MATRIMONY

- CHAPTER IX—A MASTER OF MEN

- CHAPTER X—THE MAN OR BRUTE IN EMBRYO

- CHAPTER XI—SIMON LEGREE

- CHAPTER XII—RED SNOW DROPS

- CHAPTER XIII—DICK

- CHAPTER XIV—THE NEGRO UPRISING

- CHAPTER XV—THE NEW CITIZEN KING

- CHAPTER XVI—LEGREE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE

- CHAPTER XVII—THE SECOND REIGN OF TERROR

- CHAPTER XVIII—THE RED FLAG OF THE AUCTIONEER

- CHAPTER XIX—THE RALLY OF THE CLANSMEN

- CHAPTER XX—HOW CIVILISATION WAS SAVED

- CHAPTER XXI—THE OLD AND THE NEW NEGRO

- CHAPTER XXII—THE DANGER OF PLAYING WITH FIRE

- CHAPTER XXIII—THE BIRTH OF A SCALAWAG

- CHAPTER XXIV—A MODERN MIRACLE

- BOOK TWO—LOVE’S DREAM

- CHAPTER I—BLUE EYES AND BLACK HAIR

- CHAPTER II—THE VOICE OF THE TEMPTER

- CHAPTER III—FLORA

- CHAPTER IV—THE ONE WOMAN

- CHAPTER V—THE MORNING OF LOVE

- CHAPTER VI—BESIDE BEAUTIFUL WATERS

- CHAPTER VII—DREAMS AND FEARS

- CHAPTER VIII—THE UNSOLVED RIDDLE

- CHAPTER IX—THE RHYTHM OF THE DANCE

- CHAPTER X—THE HEART OF A VILLAIN

- CHAPTER XI—THE OLD OLD STORY

- CHAPTER XII—THE MUSIC OF THE MILLS

- CHAPTER XIII—THE FIRST KISS

- CHAPTER XIV—A MYSTERIOUS LETTER

- CHAPTER XV—A BLOW IN THE DARK

- CHAPTER XVI—THE MYSTERY OF PAIN

- CHAPTER XVII—IS GOD OMNIPOTENT?

- CHAPTER XVIII—THE WAYS OF BOSTON

- CHAPTER XIX—THE SHADOW OF A DOUBT

- CHAPTER XX—A NEW LESSON IN LOVE

- CHAPTER XXI—WHY THE PREACHER THREW HIS LIFE AWAY

- CHAPTER XXII—THE FLESH AND THE SPIRIT

- BOOK THREE—THE THE TRIAL BY FIRE

- CHAPTER I—A GROWL BENEATH THE EARTH

- CHAPTER II—FACE TO FACE WITH FATE

- CHAPTER III—A WHITE LIE

- CHAPTER IV—THE UNSPOKEN TERROR

- CHAPTER V—A THOUSAND-LEGGED BEAST

- CHAPTER VI—THE BLACK PERIL

- CHAPTER VII—EQUALITY WITH A RESERVATION

- CHAPTER VIII—THE NEW SIMON LEGREE

- CHAPTER IX—THE NEW AMERICA

- CHAPTER X—ANOTHER DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

- CHAPTER XI—THE HEART OF A WOMAN

- CHAPTER XII—THE SPLENDOUR OF SHAMELESS LOVE

- CHAPTER XIII—A SPEECH THAT MADE HISTORY

- CHAPTER XIV—THE RED SHIRTS

- CHAPTER XV—THE HIGHER LAW

- CHAPTER XVI—THE END OF A MODERN VILLAIN

- CHAPTER XVII—WEDDING BELLS IN THE GOVERNOR’S MANSION

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Leopard's Spots by Thomas Dixon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Historical Fiction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.