![]()

1. Introduction

πάντων γὰρ ὅσα πλείω μέρη ἔχει καὶ μή ἐστιν οἷον σωρὸς τὸ πᾶν ἀλλ᾿ ἔστι τι τὸ ὅλον παρὰ τὰ μόρια, ἔστι τι αἴτιον (Arist. Metaph. 8.1045a 9–10)

‘In all things which have a plurality of parts, and which are not a total aggregate but a whole of some sort distinct from the parts, there is some cause’

![]()

1.1. Motivations behind the present study

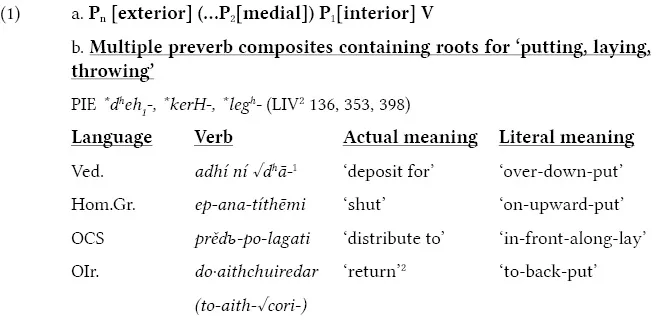

This work investigates multiple preverbs modifying verbs in some ancient Indo-European languages, specifically in Vedic, Homeric Greek, Old Church Slavic, and Old Irish. The construction under research is schematized in (1)a and exemplified in (1)b:

Each simplex base in (1)b is modified by more than one preverb, that is, a small uninflected morpheme with original spatial semantics and free-standing status. The resulting formations can develop predictable or unpredictable semantics, given the concrete basic meanings of the elements that make them up.

Preverbs and preverbation are two well-studied topics in Indo-European linguistics (cf. e.g. Rousseau 1995; Booij & Van Kemenade 2003; Chapter 3, and references therein), to such an extent that the notion of preverb itself emerged from these fields of study. However, far less attention has been paid to multiple preverb constructions of the type in (1)a-b, in which two or more such morphemes attach onto the same simplex verb. This gap in the literature may occur because the accumulation of preverbs, though possible, does not seem to be the favored procedure in ancient Indo-European languages (Kuryłowicz 1964: 174).

In spite of this general observation, a number of scholars noticed the relatively exceptional presence of multiple preverbs in Old Irish. Thurneysen (GOI 495) even wrote that “there is no restriction on the number of prepositions [i.e. preverbs] that may be employed in composition.” According to Kuryłowicz (1964: 174ff.), in Old Irish, multiple preverbs are widespread as they do not constitute an ambiguous construction: the preverb farthest from the verbal stem is clearly separated from the rest of the verbal complex, as it retains a proclitic status. McCone (1997) offered an explanation of the ordering preferences of Old Irish preverbs in what he called “primary composition”, namely the inherited layer of composition, whereby more than one preverb simultaneously attached onto the same simplex verb. However, Trudy Rossiter, a student of McCone’s, in her doctoral thesis (Rossiter 2004), challenged this view: she showed that the vast majority of Old Irish verbs with multiple preverbs can be reduced by removing the outermost preverb. This fact points to a process of formation by incremental one-by-one accumulation of preverbs (the so-called “accretion” or “recomposition”), a scenario that McCone (2006) also later embraced (cf. Chapter 7).

McCone’s (1997) monograph offered Papke (2010) a starting point to develop her comparison between Vedic and Old Irish preverb ordering, which she also extended to Homeric Greek. Papke concluded that, as there are strong correlations between preverb orderings, especially in Vedic and Old Irish, Vedic order must be historically motivated (cf. Chapters 4 and 7). In addition, in her view, Vedic verbs with multiple preverbs formed through a process that Rossiter and McCone would call “accretion” or “recomposition”: at first, only one preverb and a verbal base combine; afterwards, this established combination becomes available for the attaching of further preverb(s) (cf. Chapter 3).

Caroline Imbert dedicated several studies to Homeric Greek multiple preverbs, to their historical sources, and to the synchronic constraints ruling preverb ordering (cf. e.g. Imbert 2008). Notably, Imbert’s works are typologically oriented: she applied to Homeric Greek the category of ‘relational preverbs’ (cf. Chapter 3), which Craig & Hale (1988) identified as being among the preverbs in Rama (a Chibchan language). Accordingly, Imbert argued that Homeric Greek multiple preverbs developed from previous postpositions, as Craig & Hale showed for Rama. Zanchi (2014) also investigated Homeric multiple preverbs and their origins, but came to different conclusions from Imbert’s: according to Zanchi, multiple preverbs are believed to have developed from original adverbs, rather than from postpositions (cf. Chapter 5).

Until now, there have been no studies focusing specifically on multiple preverbs in Old Church Slavic, although both Fil’ (2011) and Zanchi & Naccarato (2016) take into account both Old Russian and Old Church Slavic data. Instead, multiple preverbs and their functions in modern Slavic languages have received much attention: for example, multiple preverbs are investigated in Czech by Filip (2003), in Bulgarian by Istratkova (2004), in Serbian by Milićević (2004), and in Russian, among others, by Babko-Malaya (1999), Filip (1999, 2003), Ramchand (2004), Romanova (2004), Svenonius (2004a, 2004b), and Tatevosov (2008, 2009). However, the system of multiple preverbs in modern Slavic turns out to be completely different from that of Old Church Slavic (cf. Chapter 6).

Along with this relative dearth of studies on multiple preverbs, it is worth mentioning another crucial gap in the relevant literature. Specifically, virtually no current studies integrate scholars’ conclusions about the origin, functions, and developments of preverbs in different languages. In order to gain a precise, and at the same time more comprehensive, understanding of the common reasons behind the behavior and historical development of preverbs, it is imperative that such an investigation takes place. For example, the above-mentioned concept of “accretion” or “recomposition” was coined by Rossiter (2004) and McCone (2006) for Old Irish, and – to my knowledge – never extended beyond its original scope. A second case in point is the so-called “Vey-Schooneveld effect”, which basically accounts for the development of Slavic preverbs into aspectual markers as a reanalysis triggered by semantic redundancy. This hypothesis was developed within Slavic linguistics and virtually was never tested elsewhere (a limited exception is Latin linguistics; cf. Chapter 6, fn. 6). As a final example, Viti (2008a, 2008b) connected the development of Homeric preverbs to markers of actionality (and transitivity) with their ability to draw anaphoric reference to discourse-active (i.e. topical) participants. Although Boley (2004) and others also regarded preverbs as elements contributing to textual cohesion, and Friedrich (1987), Coleman (1991) and Cuzzolin (1995) spoke about “discourse-oriented grammaticalization” for Latin (and generally Indo-European) preverbs, similar analyses were never performed on a wider language sample.

Thus, the choice to investigate relatively underrepresented phenomena such as multiple preverbs in a relatively wide sample of Indo-European languages aims to be a first contribution to fill the literature gaps outlined above. In particular, Vedic and Homeric Greek were selected as they represent comparably early stages of development, in which preverbs retain most of their assumed original meanings, functions, and syntactic freedom (cf. Section 1.3 for the chronology of their attestation; the most ancient attested Indo-European language, Hittite, was not included in this investigation, as it represents a divergent and to some extent problematic development, on which see Chapter 3, fn. 31). By contrast, Old Church Slavic offers a glimpse into the initial steps toward one of the possible later developments of preverbs: specifically, their subsequent grammaticalization into fully-fledged aspectual markers. In parallel, Old Irish, with its flourishing usage of multiple preverbs, provides an excellent touchstone to assess another development that preverbs may undergo: specifically, their lexicalization into semantically idiosyncratic or unpredictable composite items.

![]()

1.2. Aims and structure of the study

The aims of this work can be subcategorized as follows: (a) language-internal goals; (b) comparative goals; (c) wide-ranging goals. To begin with, for each language of the sample, the present investigation aims to (i) describe the full array of multiple preverb formations in terms of preverb combinations, verbal roots, and their frequencies; (ii) assess the extent to which multiple preverbs underwent lexicalization or grammaticalization; (iii) understand the morphosyntactic status of multiple preverbs; (iv) detect the meanings of preverbs in multiple preverb combinations; (v) provide insights into the formation process of verbs modified by multiple preverbs and preverb ordering.

Regarding (b) goals, this work seeks to (i) compare multiple preverb formations, multiple preverb combinations, the verbal bases multiple preverb formations contain, and preverb ordering; (ii) compare the statuses of multiple preverbs in the above-mentioned languages; (iii) identify, describe, and motivate common semantic shifts. With the most general level (c) goals, the study aims to (i) provide, within a relatively limited data-sample, more detailed reasons preverbs underwent the well-known lexicalization and grammaticalization; (ii) identify the pattern of formation of multiple preverb verbs; (iii) integrate references that focus on different languages to acquire a more general view of the common processes of development and their motivations.

In order to meet these goals, the present investigation takes into account a number of morphological, semantic, and syntactic parameters, which are briefly described below:

the position of preverbs with respect to that of the other pieces of preverbal morphology; the sandhi effects undergone by the elements that make up the formation; t...