- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

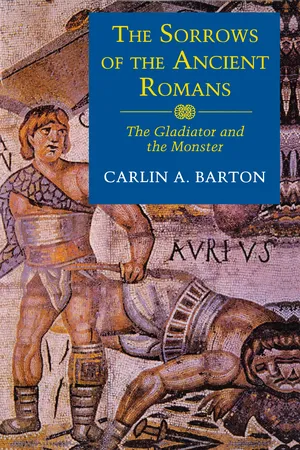

This inquiry into the collective psychology of the ancient Romans speaks not about military conquest, sober law, and practical politics, but about extremes of despair, desire, and envy. Carlin Barton makes us uncomfortably familiar with a society struggling at or beyond the limits of human endurance. To probe the tensions of the Roman world in the period from the first century b.c.e. through the first two centuries c.e., Barton picks two images: the gladiator and the "monster."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans by Carlin A. Barton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Roman Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Princeton University PressYear

2020Print ISBN

9780691010915, 9780691056968eBook ISBN

9780691219677THREE

FASCINATION

A VAIN, BARREN, EXQUISITE WASTING

The monster terrifies and attracts. He is, simultaneously, hideous and seductive; you flee him even while he fascinates you.

(Jean Brun, “Le Prestige du monstre”)1

I was fascinated—fascination being, after all, only the extreme of detachment.

(Roland Barthes, A Lover's Discourse)

LIKE THE GARGOYLE of the Gothic cathedral, the monster charms and repels within a paradoxical system of homeopathic magic. The monster fascinates; the monster cures the fascination. The monster fixates; the monster frees.2

The Romans of the late Republic and early Empire were entranced by the horrific, the miraculous, and the untoward, hypnotized by violence and cruelty and death,—as if a type of paralysis agitans afflicted the whole of the people. One of the signals of this emotional state is the proliferation of monsters. The anceps, the two-headed, the ambiguous, always important to Roman culture, was also dangerous and constricted by taboo. But in this period the filtering systems, the systems of discrimination within the culture, appear to be undergoing a transformation allowing the barriers to be breached and the grotesque and the miraculous to spill over into every aspect of Roman life.

The Curious Ones

To the degree that our speech is twisted and bent, according to Quintilian, we admire it as exquisite. The first-century teacher of rhetoric proceeds to compare the Roman admiration for the improper, obscure, swollen, base, foul, lewd, and effeminate (“impropria, obscura, tumida, humilia, sordida, lasciva, effeminata”) in speech to the placing of a higher value in the slave market on the bodies of the distorted than on those of the fair.3 There are those at Rome—the curiosi—who, according to Plutarch, pass by the handsome boys and girls for sale and proceed to the “monster market,” the teraton agora, and search out those who have three eyes or ostrich heads or weasel arms.4 Indeed, the value placed on the distorti is so high, according to Longinus, that children are deliberately deformed by being bound and confined in boxes (De sublimitate 44.5).5

In the late Republic and the early Empire the exaggerated and the astonishing permeated life in a manner and to a degree unprecedented in Roman history. The dwarf and the giant, the hunchback and the living skeleton ceased being prodigies and became pets; they ceased being destroyed and expiated and became objects of the attention and cultivation of every class. A pinhead in red livery stood beside the emperor Domitian.6 Wealthy men and women surrounded themselves with freaks and “naturals” (not to mention Greek philosophers and Maltese lapdogs),7 with miniature paintings and colossal statues. Pliny recalls, in his catalogue of human wonders, the giant Gabbara brought to Rome in the age of Claudius and the ten-foot-high titans of the Augustan city. He recalls the dwarf Cinopas among the pets of Julia, Augustus’s granddaughter, as well as the tiny freedwoman of the elder Julia.8 Calpurnius Siculus’s Corydon, like tens of thousands of his fellows, stared in amazement at the monstra of the arena (which we can identify as the giraffe, the polar bear, the seal, and the hippopotamus—creatures for whom the Romans had no names [Eclogae 7.64]). Horace tells us that the white elephant or the “diversum confusa genus panthera camelo” gave the Roman playwright tough competition (Epistulae 2.1.195-96), and he had to compete as well with the street-corner mime and its cast of distorted figures. Little “Hellenistic” or “Alexandrian” grotesques made of clay or bronze proliferated: ridiculi and obscaeni presided over the tradesman’s shop and the baker’s oven and “anatomical whimsies” combining human, animal, vegetable, and architectural forms sprouted from the walls of Nero’s Golden House.9

In English the adjective curious categorizes both the one who looks and the strange or unusual object which attracts that look. This reciprocal mirror of ideas is at the heart of the Roman concept of fascination. The “monstrous” was in the eye of the beholder; to see the Roman monster, we must look into the gaze of the Roman spectator.

Horace tells us that it is the abnormal and unusual—the curious—that captures and transfixes the eyes (Epistulae 1.6).10 It is the extraordinary that we desire.11 And so the heralds of the emperor Claudius, to draw the people to his Secular Games, cried through the streets that the games would be unlike those anyone had seen before or would see again: “ludos quos nec spectasset quisquam nec spectaturus esset” (Suetonius Claudius .21.1)12 It was the exceptionally large penises of Martial’s smoothskinned attendants at the baths that attracted the curiosus Philomusus.13 It was the exposure of Ascyltos’s outsized genitals that fixed the attention of the applauding crowd of bathers in Petronius’s Satyricon (92). Finally, it was the preposterousness of the nuptials of the seven-year-old Pannychis with the teenaged Giton that stupefied Encolpius (Satyricon 25).14

The prodigy was often, but not necessarily, hideous. The inexpressible beauty of Apuleius’s Psyche made her a freak marveled at by multitudes of natives and pilgrims “admiratione stupidi” (Metamorphoses 4.28).15 The exotic animals, but above all, the sheer magnificence of Nero’s games awed Corydon:

The splendor of the scene struck me from every side. I stood transfixed and admired it all with mouth agape, without yet being able to absorb any single marvel, when an old man who happened to be at my left remarked: “Do you wonder, peasant, that you are spellbound by such magnificence—you who know nothing of gold but only your squalid houses and huts—for even I, a white-haired and palsied old man, grown old here in the city, am stupefied by all this.”16

Beautiful or ugly, it is the monstrum, the miraculum, the ostentum that fills us with awe. Encolpius’s magically enhanced virility fills Eumolpus with horror as well as wonder (Satyricon 140).

The “monster market” was frequented by the curiosi. In modern Western culture curiosity is a neutral or even positive emotion. But for the Romans it was a sad and exasperated emotion, identified with envy and malice. “No one is curious who is not also malevolent [Nam curiosus nemo est quin sit malevolus” (Plautus, Stichus 208)].17 It is because they envy that Catullus, frantically kissing Lesbia, fears the curiosi (7).18 This equation (curiosity = envy = malice) rendered the curiosus, the “Peeping Tom,” a dreaded type in ancient Rome. Among them were numbered the skulking informers (delatores) and peering spies (speculatores, percontores).19 Such curiosi were the emperor’s brother and informer Lucius Vitellius, driven by “aemulatio prava,” emulation twisted by envy,20 and the misshapen and acid-tongued Vatinius, buffoon and delator of Nero.21

Curiosity was a product of envy, and envy of desire—“the covetous irritation of unattainable desire.”22 The curiosus was driven by frustrated longings. He or she could not resist those things in heaven and earth prohibited by the Powers That Be.23 The secret was the rare; the secrets of the gods the rarest and most forbidden—and therefore the most desired. Like Eve or Pandora, Ovid’s Aglauros cannot resist uncovering the secret of the god. Not surprisingly, given the Romans’ “physics of envy,” she reappears in Ovid’s meandering tale filled with bile and envy for her sister Herse’s magnificent match with Mercury (Metamorphoses 2.552-61, 637ff.). Like Aglauros, the sisters of Apuleius’s gorgeous Psyche are paradigms of the curiosi. Out of poisonous envy of Psyche’s good fortune, they instigate her to expose the fatal secret of the god.24 The curious, the polupragmones (“busybodies”), according to Plutarch, pass over the stories and subjects of common speech and pick out “ta kruptomena” and “lanthanonta,” the hidden scandals of every household (De curiositate 3 Moralia 516d-f ). The secret and sexual offenses of the women, in particular, charm the scopophiliac, the “philopeuthes.”25 The “marriage” of the prepubescent maid beckons Domatilla and Encolpius (already deeply in trouble for having witnessed the secrets of the god Priapus) to a chink in the door (Satyricon 25).26 The nocturnal metamorphosis of the naked witch of Thessaly lures Apuleius’s Lucius, another indefatigable curiosus, to spy through another crack (Metamorphoses 3.22).

Curiosity was a hunger.27 The curious (and resentful) eye was often linked in Roman thought with metaphors of eating and cannibalism. The malicious Vitellius feasted his eyes on the spectacle of his enemy’s death (“se pavisse oculos spectata inimici morte iactavit” [Tacitus, Historia 3.39]),28 as Encolpius feasted his on the sight of his rival being beaten (Satyricon 96).29 The appet...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- The Gladiator

- The Monster

- Modern Works Cited

- Index