Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses the important structures of the neck, most of which can be seen and felt in the thin patient. Few of these structures are apparent in the obese, pyknic individual with a short neck; however, certain landmarks can always be found. The sternomastoid muscle, running from one corner to the other of a quadrilateral area, formed by the anterior midline, the clavicle, the leading edge of the trapezius, and the mastoid–mandibular line divides the side of the neck into anterior and posterior triangles. The apophyseal joints lie oblique in the sagittal plane and incline medially in the coronal. This alignment lacks the architectural stability of the dorsal and lumbar areas of the spine; however, it permits more movement. A fail-safe locking mechanism is provided by the abutment of the superior leading edge of the inferior facet into the articulo-transverse angle of the joint above. The joint capsules are richly innervated with pain and propioceptive receptors—more so than in the corresponding joints lower in the spine—so that awareness of head and neck movement is enhanced.

INTRODUCTION

Man sees before he understands. The accuracy (but not the beauty) of Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, astonishing and unsurpassed after 400 years, disappears in his portrayal of structure whose function was not known to him. He knew what bones and muscles do, and could interpret their anatomy in architectural and engineering terms; and he drew them with a photographic regard for correct detail. He was the first biomechanic. He did not know what nerves do, and drew them as he thought they should look according to the metaphysics of Galen and Bacon∗. We can not afford to smile at their naivety. We are as guilty of false extrapolation, and as restricted by orthodoxy as the medieval philosophers. Vesalius was four years old when Leonardo died. Within one generation the foundations of topographical anatomy, derived from dissection, had been laid so securely that all further details of anatomical knowledge have been mere additions to Vesalius’ work.

This is not the place to discuss the importance of descriptive anatomy in the undergraduate curriculum; but its position in the clinician’s approach to accurate diagnosis and management remains paramount and unchallenged. In recent years much attention has been paid to the detailed topographical structure of the neck. This chapter is unashamedly selective in concentrating on some of these aspects. It is not an attempt to teach anatomy to the orthopaedic surgeon; or to replace the cadaver and Gray as his primary source (even less is the word ‘primary’ a Freudian slip).

The neck conveys vital structures from and to the head and trunk. It enables the head to be placed in a position to receive from the environment all information other than that provided by touch. We need to know as much as possible about these structures, about movement of the head relative to the neck and the neck relative to the trunk; disorders of the cervical spine will affect one or other of these things.

SURFACE ANATOMY

Many of the important structures of the neck can be seen and felt in the thin patient. Less is apparent in the obese, pyknic individual with a short neck, but certain landmarks can always be found.

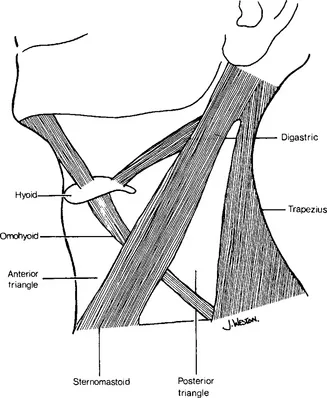

The sternomastoid muscle, running from one corner to the other of a quadrilateral area, formed by the anterior midline, the clavicle, the leading edge of the trapezius and the mastoid–mandibular line, divides the side of the neck into anterior and posterior triangles (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Muscular triangles of the neck

The posterior triangle contains little which is visible on inspection. Palpation of the base of the triangle (which is really a pyramid) finds the first rib, crossed by the subclavian artery, the lower trunks of the brachial plexus and perhaps a cervical rib or its fibrous prolongation. Higher, the accessory nerve, running forwards to the sternomastoid, divides the triangle into an upper ‘safe’, and a lower ‘dangerous’ area (Grant, 1951). In this upper area the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae can be deeply felt.

There is more to be seen, and felt, in the anterior triangle. The external jugular vein, and the platysma, cross the sternomastoid; and both stand out in the thin singer. The ‘Adams’ apple’∗ moves with swallowing, and the pulsation of the carotids is often visible. Below the body of the hyoid, the neurovascular bundle can be compressed against the carotid tubercle of the sixth vertebra; demonstrating how easily accessible is the spine through this area. In the apex of the triangle, the transverse process of the atlas is palpable immediately behind the internal carotid artery; and the finger tip can roll over the tip of the styloid process and the stylohyoid ligament. In the anterior midline can be usually seen, and always felt, the anterior arch of the hyoid, the notch of the thyroid cartilage, the cricoid and the upper rings of the trachea. With advancing age, the horizontal creases in the skin become more pronounced. Whenever possible, operative incisions should occupy one of these creases, in the interests of healing, if not beauty.

The currently fashionable long hair of both sexes makes inspection of the back of the neck difficult. Fortunately, fashion is fickle. The vertebra prominens, which may be the spinous process of the seventh cervical or the first thoracic vertebra, marks the lower end of the midline sulcus formed by the ligamentum nuchae in its leap to the occiput. The rounded ridge on either side of the sulcus is made by splenius capitis as the origin of trapezius is tendinous. The vertebra prominens is the top of the ‘dowager hump’ seen in patients with cervical spondylosis.