eBook - ePub

Decision Processes in Visual Perception

- 412 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Decision Processes in Visual Perception

About this book

Decision Processes in Visual Perception explores the relationships between the organization of a complex visual pattern by the perception system and the molecular activity involved in the discrimination of differences in magnitude or intensity between two stimulus elements. The text discusses the basic principles of discrimination, identification, and self-regulation of the perception system; demonstrates how adaptive decision modules emerge from multiple constraints; shows how combinations of simple decisions lead to complex judgmental tasks; and synthesizes traditional approaches to perception in order to clarify the crucial and pervasive role of these modules in the overall activity of perceptual organization. Psychologists, neuroscientists, molecular biologists, and physiologists will find the book invaluable.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Simple Decision Processes

1

Introduction

Publisher Summary

Since the time of Aristotle, it has been appreciated that the ways in which men categorize the world have only a restricted validity. In particular, the habit of regarding certain aspects as stable entities depends upon the grain of the time scale employed. This chapter discusses the evolution of the vertebrate visual system and the roles of the visual system in human evolution. By interpreting the genetically programmed sequence of changes in the embryos of vertebrate animals as a cumulative record of past evolutionary stages, Polyak has reconstructed the major steps in the development of the vertebrate eye and visual system. Many of the basic processes of space perception were already highly developed in the early marine ancestors of the vertebrates. For an organism already heavily reliant on vision, the path toward more light, warmth, oxygen, and food would naturally lead up from the sea bed to the upper regions of the water, and thence to the higher evolutionary possibilities opened up on land by the perfection of the visual system.

What is a man but nature’s finer success in self-explication? What is a man but a finer and compacter landscape than the horizon figures—nature’s eclecticism?

R. W. Emerson, “Essays” (Ser. 1, xii, p. 352.)

Within the dozen or so generations since Descartes examined the inversion of images by the lens of an eye excised from an ox, the study of responses by the vertebrate system to light falling on the retina has progressed from a delineation of its gross anatomy to the recording of electrical activity from a single cell in the cortex of a living cat. While such a dramatic improvement in the techniques of physiological measurement has undoubtedly led to a more detailed understanding of the mechanisms involved, it carries with it the risk that some of the more molar influences on the process of visual perception may be underrated or forgotten. Even at the behavioural level, with which most of this book is concerned, it is all too easy to lose sight of the importance of certain general principles in the concentration on experimental detail often needed to discern some pattern in a set of findings. Because of this, and because the theories developed in this book have been partly shaped by considerations beyond those of the immediately relevant data, it is useful to begin by recalling some of the most general and pervasive influences on visual perception.

Process, Constraint and Structure

At least since the time of Aristotle, it has been appreciated that the ways in which men categorize the world have only a restricted validity. In particular, the habit of regarding certain aspects (such as flowers or nerve cells) as stable entities depends upon the grain of the time scale employed. Given a coarser grain (as in time-lapse photography), then, as William James remarks, “mushrooms and the swifter-growing plants will shoot into being · [and] annual shrubs will rise and fall from the earth like restlessly boiling water springs” (1890, 1, p. 639). On a still larger scale, even such “permanent” features as massive rock formations, can be seen to be not static entities, but processes, which occur in accordance with certain natural laws. From stellar bodies down through animal populations to cells, molecules and atoms, these processes are continuously changing in space and in time. Meanwhile, irrespective of the level, the behaviour of their constituent elements seems (from the inevitably limited viewpoint of any member of such a universe) to be neither completely determined nor completely random, but to be subject to the control of certain probabilistic constraints. It is the operation of these constraints that determines the character of any process. For example, as Weiss (1969) points out, a living cell remains the same, despite the continuous reshuffling and exchange of its molecular components; in the same way, a human society can retain its identity despite the turnover in population from birth, death and migration. In both cases, it is the constraints imposed upon these processes which determine their nature, structure and development.

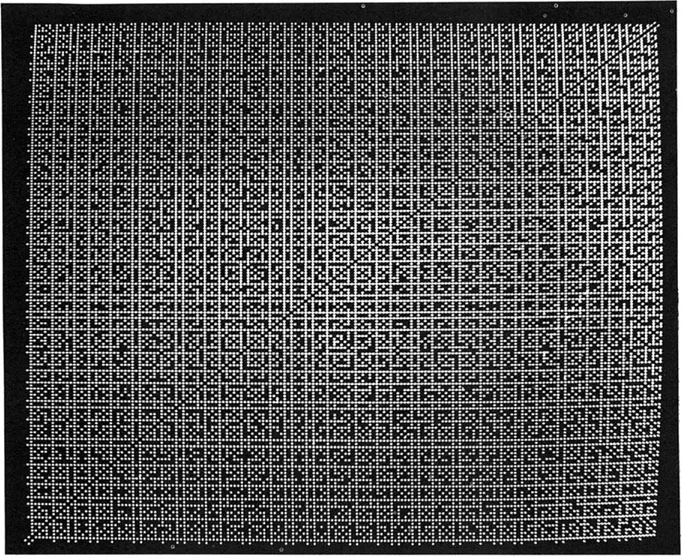

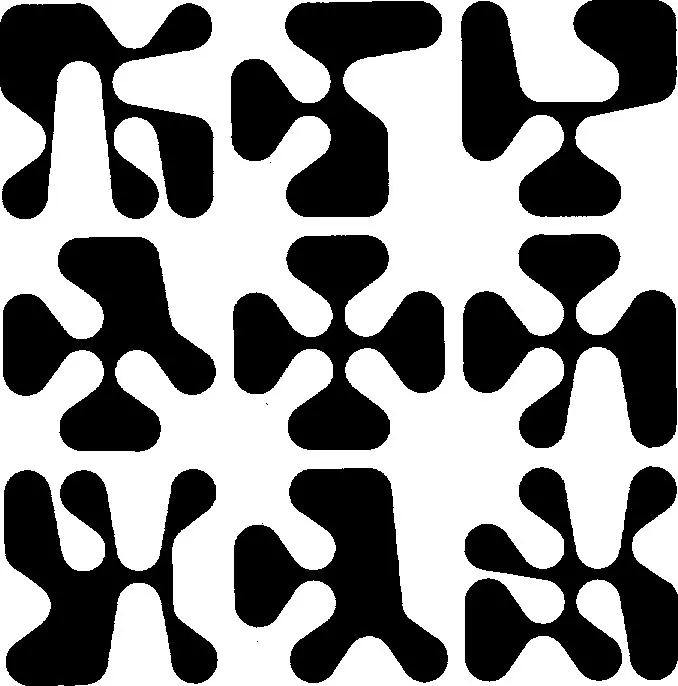

A related insight, which was not emphasized in earlier associationist accounts of perception, but has since become widely recognized, is that structure, in the form of predictable relations among the distinguishable elements constituting a process, is omnipresent in the natural world. Any modern, illustrated encyclopaedia contains an abundance of striking examples, from both the organic and the inorganic world, of intricate structures imparted by the multiplicity of constraints controlling cellular reproduction and crystalline accretion. As well as these relatively familiar instances, however, structure may also appear when it is least expected, as in the layering effects observed when “random” numbers, generated by some computer programmes, are represented visually, or, as in Fig. 1, where apparently simple constraints produce an unexpectedly complex pattern. In a similar way, graphic artists may impart an elusive structure by the use of implicit constraints, as in the shapes shown in Fig. 2. Although the relevant constraints are often difficult to specify, the prevalence of detectable structure and regularity in nature has been eloquently described by a variety of thinkers, including the biologist D’Arcy Thompson (1917) and the poet Hopkins (1972), and has been studied in phenomena as diverse as the branching of blood vessels or the biography of a sand dune.

On this view, the structure of the elements composing some process may be regarded as providing a history of its growth or formation, as well as information about its composition and properties, the forces acting upon it, its interaction with other processes and its likely future development. For example, a swarm of parallel crevasses in the brittle surface of a glacier indicates the presence and direction of compression forces as the underlying flow is checked by some obstacle, while the jagged edges of the surrounding peaks reveal the source and direction of previous glaciation. On a smaller scale, the thickness, cross-section and economical design of earlier wrought iron implements constitute a legible signature of the operations performed by the blacksmith to bend, twist and beat a uniform bar of metal into a useful tool. Thus, the constraints which may be important in any particular case are diverse, and include the electrical forces which preserve the integrity of an atom, chemical reactions such as oxidation, electromagnetic effects, gravitational forces, the effects of heat and cold, processes of manufacture and erosion by wind and water.

In turn, the effects of these constraints can be classified for convenience into two main kinds. The first is concerned with the formation of elements, that is, comparatively simple, unitary processes which recur throughout nature, such as atoms, molecules, crystals or cells. The second has to do with the linkage of these elements into more complex processes, such as the regular stacking of particles in a crystal, the spiral arrangement of stars in a galaxy, or the functional sandwiching of epidermal, palisade and mesophyll cells within a single leaf. It is true that, within certain broad limits, the classification of a process as an element itself or as a configuration of simpler elements is arbitrary, and the natura...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Inside Front Cover

- Copyright

- Preface

- Dedication

- Part I: Simple Decision Processes

- Part II: Confidence and Adaptation

- Part III: Complex Decision Processes

- References

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Decision Processes in Visual Perception by D. Vickers, Edward C. Carterette,Morton P. Friedman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.