eBook - ePub

Behind and Beyond the Meter

Digitalization, Aggregation, Optimization, Monetization

- 460 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Behind and Beyond the Meter

Digitalization, Aggregation, Optimization, Monetization

About this book

The historical ways in which electricity was generated in large central power plants and delivered to passive customers through a one-way transmission and distribution network – as everyone knows – is radically changing to one where consumers can generate, store and consume a significant portion of their energy needs energy locally. This, however, is only the first step, soon to be followed by the ability to share or trade with others using the distribution network. More exciting opportunities are possible with the increased digitalization of BTM assets, which in turn can be aggregated into large portfolios of flexible load and generation and optimized using artificial intelligence and machine learning.

- Examines the latest advances in digitalization of behind-the-meter assets including distributed generation, distributes storage and electric vehicles and – more important – how these assets can be aggregated and remotely monitored unleashing tremendous value and a myriad of innovative services and business models

- Examines what lies behind-the-meter (BTM) of typical customers and why managing these assets increasingly matter

- Describes how smart aggregators with intelligent software are creating value by optimizing how energy may be generated, consumed, stored o potentially shared o traded and between consumers; prosumers and prosumagers (that is, prosumers with storage)

- Explores new business models that are likely to disrupt the traditional interface between the incumbents and their customers

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Visionaries, dreamers, innovators

Outline

Chapter 1

What lies behind-the-meter and why it matters?

Fereidoon Sioshansi, Menlo Energy Economics, San Francisco, CA, United States

Abstract

Until recently, customers bought all kWhs they used from the network and paid volumetrically based on bundled regulated tariffs. This is beginning to change as some consumers generate some or virtually all their kWhs from rooftop PV panels. Moreover, rapid technological advancements make it possible for prosumers to become prosumagers by adding storage and/or engage in other forms of transactions with and among each other. Such peer-to-peer trading is likely to proliferate as regulators relax the prevailing restrictions. Even more consequential, however, is the emergence of smart intermediaries who can aggregate large numbers of behind-the-meter assets and monitor and optimize the entire portfolio.

Keywords

Behind-the-meter; disruptive technologies; innovative business models; regulation of utility distribution networks; distributed generation; distributed storage; peer-to-peer energy trading

1.1 Introduction

This chapter, being the first in the volume, starts with the question that many a reader may legitimately ask upon coming across the book’s title—namely, what lies “behind-the-meter” (BTM) and why does it matter? Why devote a whole volume to the topic, and what can be gained from reading such a book? These are perfectly good questions.

As mentioned in the book’s Introduction, for most of its history, the electricity sector was defined to cover essentially, if not exclusively, what lies upstream of the customers’ meter—namely generation assets and the extensive transmission and distribution network that delivers power to customers. A typical textbook might illustrate this traditional utility-centric paradigm as in Fig. 1.1, with customers’ meters as the terminal point.

This view, which persists to this day in many a mindset, misses the most important part of the picture, namely, what do customers do with the electricity that is finally delivered to their meter—and the ubiquitous electrical sockets that feed the devices that use electricity within their premises.

What customers traditionally did with the electricity, of course, has changed over time as new applications and devices were added, most notably air conditioning, which is now taken for granted in many parts of the world as an essential necessity. But until recently, customers—with a few exceptions—bought all kWhs they used from the network that connects them to upstream generation assets. kWhs consumed equaled kWhs delivered to the meter. Moreover, the vast majority of customers paid for the kWhs delivered based on bundled regulated tariffs, where the term bundled in this context means that the tariff included the total cost of all upstream investments such as generation, transmission, and distribution plus costs of retailing services, applicable taxes, and levies.

This picture is beginning to change in some parts of the world as some consumers can generate some or virtually all the kWhs they consume from rooftop PV panels. For these prosumers, kWhs consumed no longer equal kWhs delivered and paid for from the network. In fact, in places where net energy metering is available, the prosumers may pay little or virtually nothing for service if their net consumption—that is, total kWhs consumed less total kWhs generated and fed into the network—is small or zero. In some cases, prosumers who generated more than they consumed may in fact get a refund from the network operator.1

Currently, the number of prosumers is small relative to consumers. But if the relative cost of self-generation is lower than buying bundled kWhs from the network—as it is in places such as Australia2—one can expect their numbers to rise.3 In the state of California, for example, self-generation is expected to reduce the number of kWhs purchased from the grid by an estimated 50 GWh by 2030 as illustrated in Table 1.1. The same phenomenon is already happening in Australia, a country with a population of 24 million with over 2 million solar roofs.

Table 1.1

| 2018 | 2030 | |

|---|---|---|

| Consumption | 260,000 | 340,000 |

| Sales | 260,000 | 290,000 |

CEC projections of consumption versus sales for California, in GWhs,4 shows a growing departure between the two over time.

California Energy Demand, 2018-2028 Preliminary Forecast, California Energy Commission, Aug 2017, CEC-200-2017-006-SD.

As these examples illustrate, the fact that kWhs consumed will no longer equal the kWhs sold to customers is not something many utility executives could have imagined a mere decade ago. A decade from now, the phenomenon will be pronounced in many parts of the world as residential, commercial, and even industrial customers generate some of their juice from rooftop solar—or in the case of some large commercial and industrial customers buy it from an alternative source, not necessarily the regulated utility that serves them.

The next major shock is likely to come from rapid technological advancements in energy storage, not just batteries but all sorts of storage devices and media such as storing hot water or ice for use at a later time. Such opportunities allow some prosumers to become prosumagers by storing some of their self-generated power for use at later times, such as after the sun goes down. Again, the economics of such options critically depend on bundled retail prices, including taxes, levies, and other charges that are usually embedded in the tariffs.

If prosumers are offered little or none for the excess generation fed into the network that increases the attractiveness of self-storage. Electric vehicles (EVs) are among the emerging BTM technologies that may act as distributed storage. Their numbers are expected to rise exponentially in many parts of the world over the next decade or two. The storage capacity of several million EVs, if they are aggregated and collectively managed, can serve as a huge storage capacity on a typical network.

Such scenarios are already happening and their impact is beginning to get noticed in places like California or Norway, where the penetration of solar PVs and EVs is high, respectively.

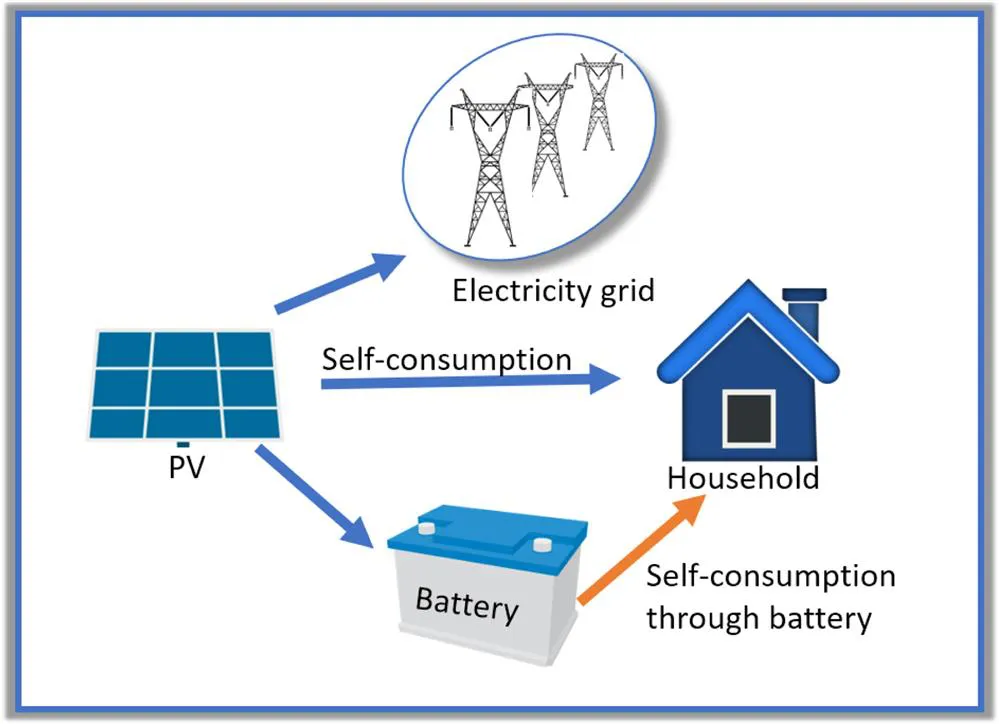

Fast forward, so to speak, and the picture that emerges may look like the one illustrated in Fig. 1.2, where electricity may be generated from solar PV panels on millions of customers’ roofs, feeding the network—rather than taking from the network at least on sunny hours of the day—and charging the storage devices while meeting the customers’ needs. An example of such a setup is described in the following chapter by Schlesinger. Of course, not all customers would fit this picture, but some could. The point is not how many consumers may turn into prosumers or prosumagers but that the traditional view of the industry is likely to undergo significant change, that is, the contrast between Figs. 1.1 and 1.2.

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Author biographies

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part One: Visionaries, dreamers, innovators

- Part Two: Implementers & disrupters

- Part Three: Regulators, policymakers & investors

- Epilogue

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Behind and Beyond the Meter by Fereidoon Sioshansi,Fereidoon P. Sioshansi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Energy Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.