- 100 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Bioelectronics: A Study in Cellular Regulations, Defense, and Cancer examines biological reactions on the electronic level. Chapters in the book discuss topics on the ionization potential and electron affinity; the charge transfer reactions; defense mechanisms of living organisms; and the description of the mechanisms governing the growth and proliferation of cancer cells. Biochemists, oncologists, pharmacologists, and pharmaceutical researchers will find the book invaluable.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bioelectronics by Albert Szent-Györgyi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

INTRODUCTION

Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses the role of molecular biochemistry in studying cells. The cell is a machine driven by energy. It can, thus, be approached by studying matter or by studying energy. The study of matter, or structure, leads to molecular biochemistry and the steric factor approach that dominates present biochemistry. Molecular biochemistry left no room either for one of the most fundamental rules of life, that of nonadditivity. If an electron and a nucleus are put together in a meaningful way, a hydrogen atom is born that is more than an electron and a nucleus. If atoms are built into a molecule, again something new is born that can no longer be described in terms of atoms. The same holds true when small molecules are built into macromolecules, macromolecules into organelles, organelles into cells, cells into organs, organs into an individual, and individuals into a society.

THE PROBLEM IS STATED

If you would ask a chemist to find out for you what a dynamo is, the first thing he would do is to dissolve it in hydrochloric acid.* A molecular biochemist would, probably, take the dynamo to pieces, describing carefully the helices of wire. Should you timidly suggest to him that what is driving the machine may be, perhaps, an invisible fluid, electricity, flowing through it, he will scold you as a “vitalist.”

No doubt, molecular biochemistry has harvested the greatest successes and has given a solid foundation to biology. However, there are indications that it has overlooked major problems, if not a whole dimension, for some of the most exciting questions remained unanswered, if not unasked. It failed to explain the wonderful subtlety of cellular regulations. Neither did it explain the mechanism of energy transduction, the transduction of chemical energy into mechanical, electric, or osmotic work. These transformations are closely connected to the very nature of life. I do not know what life is, but I can tell life from death, and know when my dog is dead: when he moves no more, has no reflexes, and leaves my carpet dry, that is, performs no more energy transductions. These failures, hiding in the shadow of success, warrant a fresh approach.

The cell is a machine driven by energy. It can thus be approached by studying matter, or by studying energy. The study of matter, or structure, leads to molecular biochemistry and what D. D. Eley calls the steric factor approach which dominates present biochemistry. I will approach from the energy side. Needless to say, a final understanding can be achieved only by the synthesis of the two lines which are but the two sides of the same coin.

Molecular biochemistry left no room either for one of the most fundamental rules of life, that of nonadditivity. One particle, plus one particle, put together at random, are two particles, 1+1=2; the system is additive. But if two particles are put together in a meaningful way then something new is born which is more than their sum: 1+1 > 2. This is the most basic equation of biology. It can also be called organization. This equation holds true for the whole gamut of complexity. If an electron and a nucleus are put together in a meaningful way, a hydrogen atom is born which is more than an electron and a nucleus. If atoms are built into a molecule, again something new is born which can no longer be described in terms of atoms. The same holds true when small molecules are built into macromolecules, macromolecules into organelles, organelles into cells, cells into organs, organs into an individual, and individuals into a society, etc. If living nature has qualities which are very different from those of the inanimate this is not because it is subject to different laws, but because life drives this “putting together” much farther than the inanimate world does.

This book is devoted to the question of whether or not there is a closer analogy between the dynamo and the living system. This latter, too, may be permeated by an “invisible fluid,” the particles of which, the electrons, are more mobile than molecules and carry energy, charge, and information, and act as the fuel of life. These electrons may help to connect molecules to meaningful structures and may also be responsible for the charming subtlety of biological reactions.

THE IONIZATION POTENTIAL AND ELECTRON AFFINITY

Approaching biology from the energy side the first question is: What is energy? What does it mean that an aggregate of atoms or molecules, like the cell, has energy? To simplify this problem let us consider one atom only, the simplest of all, hydrogen. What does it mean that hydrogen has energy?

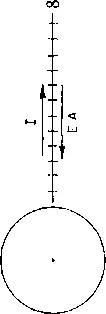

In Fig. 1 is represented an H atom. The circle stands for the electron of H moving rapidly around the nucleus, the dot in the middle, the proton. The nucleus, as such, has no energy, nor has the electron. So, if H has energy, it can reside only in the relation of the two. The electron would, evidently, fly off if it were not held by forces pulling it toward the nucleus. We can measure these forces by measuring the energy which is needed to tear off the electron from the atom, and take it to infinity, that is, to a distance at which it interacts with the nucleus no longer. This tearing off is symbolized in Fig. 1 by the straight line leading from the atom to infinity; the energy needed for doing this against the attraction of the nucleus is what is called the ionization potential (I), which is usually measured in electron volts (eV).

The ionization potential of H is about 13 eV. This means that I would have to invest 13 eV worth of energy to tear the electron off. I could get my invested energy back by dropping the electron from infinity to its now empty orbital. This amount of energy released by the dropping electron is the electron affinity.

If, somehow, I would cause the electron to be attracted by the nucleus only half as strongly, then the ionization potential would be only 6.5 eV. I would need, now, only 6.5 eV to take the electron off, but would get only 6.5 eV by dropping it back. The electron behaves now as if I had taken it halfway toward infinity, between notches 6 and 7 in Fig. 1.

If, in this new situation, the electron comes off earlier, this also means that it will interact easier with other atoms or molecules. The ionization potential is thus a measure of both the electron’s energy and reactivity. The lower the ionization potential, the greater the electron’s energy and reactivity, while the greater electron affinity indicates a greater willingness of the orbital to accommodate the electron.

One of the main reactions discussed in this book will be the transfer of an electron from the occupied orbital of one molecule or atom to an empty orbital of another, the so-called charge transfer. The particle giving the electron is called the donor (D) while the one receiving the electron is called the acceptor (A). The transfer could also be called a DA interaction.

In theory, we could find out how much energy we use or release in transferring an electron from D to A, by transferring the electron in two steps, first by taking it away from D, removing it to infinity, then dropping it from infinity onto the empty orbital of A, as symbolized in Fig. 2. In this figure the thick lines stand for occupied orbitals, the thin lines for empty ones. The electron in such interactions is usually transferred from the highest filled orbital of the donor to the lowest empty orbital of the acceptor. In this procedure we would have to invest in the first step an amount of energy which corresponds to the ionization potential of D. In the second step we would gain energy which is equal to the electron affinity of A. The energy gained or us...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- PREFACE

- Chapter I: INTRODUCTION

- Chapter II: ELECTRONIC MOBILITY

- Chapter III: BIOLOGICAL RELATIONS

- Chapter IV: PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY

- Chapter V: CONCLUSION

- Chapter VI: EPILOGUE

- BIBLIOGRAPHY