Section 1. Environmental and Genetic Factors Influencing Stress Reactivity

Glossary

Maternal deprivation: separation of mother and infant during the stress-hyporesponsive period, which needs to last for at least 8 h for immediate and persistent effects on the neuroendocrine regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.Stress-hyporesponsive period: a period of reduced adrenal corticosterone and pituitary adrenocorticotrophic hormone release in response to stress lasting in the rat from postnatal days 4–14.Based primarily on the pioneering work of the late Hans Selye, the stress response has become somewhat synonymous with the release of hormones from the pituitary and adrenal glands. Thus, in most adult mammals stimuli presumed to be stressful result in a systematic release of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) and the subsequent secretion of glucocorticoids from the adrenal. This simplistic view of the pituitary–adrenal axis as first described by Selye has been elaborated on extensively. Thus, the regulation of the so-called stress hormone clearly involves specific peptides synthesized and stored in the brain (i.e., corticotropin-releasing factor ((CRF) and arginine vasopressin (AVP)) and brain-derived neurotransmitters (i.e., noradrenaline). Thus the brain must be included as a critical stress-responsive system. However, the sequence of responses observed consistently in the adult are in many ways very different in the developing organism. Abundant evidence indicate that the rules that govern the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis in the adult are very different in the neonate. This is best appreciated in rodent. Thus, in this chapter, the ontogeny and regulation of the rodent HPA is discussed. In addition, developmental aspects of the human HPA axis during the first years of life are reviewed.

Stress-hyporesponsive period

In 1950, a report appeared that first indicated that the neonatal response to stress deviated markedly from that observed in the adult rodents and thus, created a field of inquiry that has persisted for over four decades. Using depletion of adrenal ascorbic acid as the indicator of the stress response, Jailer reported that the neonate did not show any response to stress (Jailer, 1950). By the early 1960s, Shapiro placed a formal label on this phenomenon and designated it as the “stress nonresponsive period” (SNRP) (Shapiro et al., 1962). It is important to note that for the most part the basis for this description was the inability of the rat pup to show significant elevations of corticosterone (CORT) following stress. There was one study that received little attention at the time but did raise important questions concerning the validity of the notion of an SNRP. In that study, in addition to exposing the pup to stress and demonstrating a lack of CORT response, another group was injected with adrenocorticoid hormone (ACTH) (Levine et al., 1967). These pups also failed to elicit a CORT response, which indicated that one of the factors contributing to the SNRP could be a decreased sensitivity of the adrenal to ACTH. Therefore, it was conceivable that other components of the HPA axis might be responsive to stress. The resolution of this question was dependent on the availability of relatively easy and inexpensive procedures for examining other components of the HPA axis. The methodological break-through, which altered most of the endocrinology and had a major impact on our understanding the ontogeny of the stress response, was the development of radioimmuneassay (RIA) procedures.

The initial impact of the RIA was to change the designation of this developmental period from the SNRP to the “stress-hyporesponsive period” (SHRP). This change was a result of studies that showed a small but significant rise in CORT when measured by RIA (Sapolsky and Meaney, 1986). Although the response of the adrenal was reduced markedly during the SHRP, the adrenal is capable of releasing small amounts of CORT when exposed to certain types of stress.

When investigators began to examine other components of the neonates’ HPA axis it became apparent that the SHRP is still a valid concept. However, in order to confront this question, we will examine the development of several components of the HPA axis. These include the adrenal, the pituitary, and the brain.

SHRP, the adrenal, and corticosterone

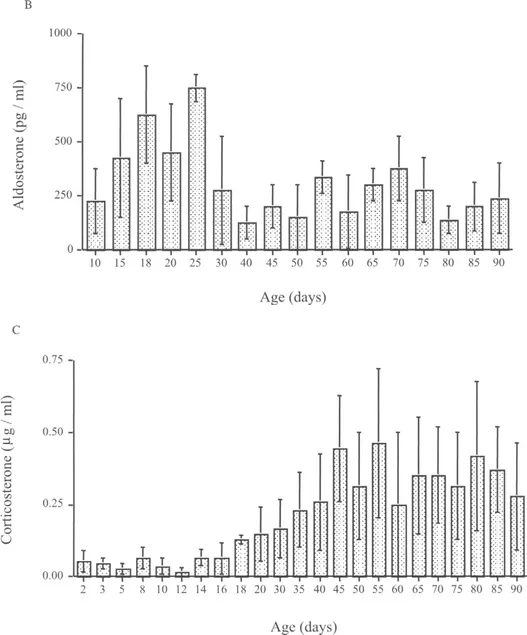

It is generally agreed that in response to most stressors the neonate fails to elicit adrenocortical response, or does so minimally (Walker et al., 2002). There are several features that characterize the function of the pup’s adrenal. The first and most obvious characteristic of the adrenal function during SHRP is that basal levels of CORT are considerably lower than that observed immediately following parturition and that these low basal levels continue to predominate between postnatal days 4–14. Further, numerous investigators have reported that the neonate can elicit a significant increase in plasma CORT levels (Walker et al., 2002). However, invariably the magnitude of the response is small compared to older pups that are outside the SHRP and of course to the adult. Thus, whereas the reported changes in CORT levels following stress in the adult can at times exceed 50μg/dl, rarely does the infant reach levels that exceed 10μg/dl during the SHRP. These levels are reached only under special circumstances, which shall be described later. Thus, the ability of the neonatal adrenal to secrete CORT seems to be impaired markedly. Morphological, biochemical, and molecular biological studies suggest that the development of the adrenal cortex is in part responsible for this phenomenon. Chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla and maternal factors are also important (see Section “Adrenal Sensitivity”).

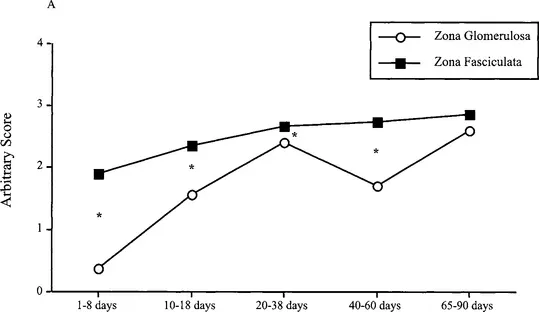

The mature adrenal cortex in the rodent consists of three concentric steroidogenic zones that are morphologically and functionally distinct: the zona glomerulosa (ZG), the zona intermedia, and the zona fasciculata (ZF)/reticularis (ZR). The ZG, ZF/ZR have unique expression of specific steroidogenic enzymes that defines the specific steroid produced by each zone (Parker et al., 2001). Thus, cytochrome P450 aldosterone synthase (P450aldo) is produced within the glomerulosa to produce the mineralocorticoid aldosterone, whereas P450 11β-hydroxylase (P45011β) defines the glucocorticoid producing zona fasciculata/reticularis. In many mammalian species the development of the adrenal cortical layers and steroidogenic enzyme synthesis primarily occur during fetal life (Parker et al., 2001). However, cells expressing P45011β clearly resolve into their cortical layer by the third day after birth (Mitani et al., 1997).

The development of adrenal cortical zones are closely related to the development of the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla (Bornstein and Ehrhart-Bornstein, 2000). As shown by Bornstein and co-workers, a variety of regulatory factors produced and released by the adrenal medulla play an important role in modulating adrenocortical function. Isolated adrenocortical cells loose the normal capacity to produce glucocorticoids, whereas culture of adrenocortical cells with chromaffin cells causes marked upregulation of P450 enzymes and the steroidogenic regulatory protein (StAR), which mediates the transport of cholesterol to the inner mitochondrial membrane where steroidogenesis occurs (Bornstein and Ehrhart-Bornstein, 2000). On the 18th day of fetal life, cells containing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the initial and rate-limiting enzyme of catecholamine synthesis, and a marker for adrenal medullary cells, are found intermingled with cortical cells expressing P45011β in the area that is later defined as the ZF/ZR. However, the adrenal medulla becomes a well-defined morphological region at the end of the first week of life (Pignatelli et al., 1999), at a midpoint in the SHRP. Within this period and until PND 29, the TH enzymatic activity increases (Lau et al., 1987). It is during this time that most of the adrenocortical cellular proliferation activity is observed, but limited to the outer cortex: ZG and ZF. Studies that utilized a specific antibody that recognizes antigens found specifically in these cortical cells of the rat adrenal (IZAgl and Ag2) showed faint ZF immunostaining on the first day of postnatal life. A progressive increase in staining was observed until 18–20 days postnatally. Taken together, these data suggest that the limited adrenocortical activity in the infant rat is greatly due to the maturity of the steroidogenic enzymatic pathways of the adrenal during the SHRP (see Fig. 2). In addition, there is evidence that suggests that the autonomic nervous system through the adrenal medulla is also an important contributor to the regulation of adrenocortical development through paracrine activity (Pignatelli et al., 1999).

Fig. 2 Postnatal adrenal cortex function in the rat. Panel A depicts expression of adrenal cortex enzyme 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogena...