- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fundamentals of Human-Computer Interaction

About this book

Fundamentals of Human-Computer Interaction aims to sensitize the systems designer to the problems faced by the user of an interactive system. The book grew out of a course entitled ""The User Interface: Human Factors for Computer-based Systems"" which has been run annually at the University of York since 1981. This course has been attended primarily by systems managers from the computer industry. The book is organized into three parts. Part One focuses on the user as processor of information with studies on visual perception; extracting information from printed and electronically presented text; and human memory. Part Two on the use of behavioral data includes studies on how and when to collect behavioral data; and statistical evaluation of behavioral data. Part Three deals with user interfaces. The chapters in this section cover topics such as work station design, user interface design, and speech communication. It is hoped that this book will be read by systems engineers and managers concerned with the design of interactive systems as well as graduate and undergraduate computer science students. The book is also suitable as a tutorial text for certain courses for students of Psychology and Ergonomics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fundamentals of Human-Computer Interaction by Andrew F. Monk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Ingeniería general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE USER AS A PROCESSOR OF INFORMATION

INTRODUCTION TO THE USER AS A PROCESSOR OF INFORMATION

The aim of this book is to introduce concepts and examples which allow the designer to think more clearly about the problems faced by the users of interactive systems and their solution. This first section presents over-views of four areas from Cognitive Psychology.

Cognitive Psychology, or ‘Human Information Processing’ as it is sometimes known, is central to the development of the kind of sensitivity to human factors problems that the book aims to create. It provides the conceptual framework needed to think about the abilities and limitations of the user. If the ‘human’ part of the human-computer interaction is to be viewed as a part of a complete information processing system then it is necessary to describe him in terms of his information processing capacities. This perspective is not commonly taken outside the behavioural sciences and is developed in detail to ensure a full appreciation of the rest of the material in the book. It is illustrated by describing the strengths and weaknesses of the human information processing system as they relate to the user interface.

The first two chapters are concerned with how we take in information. This kind of human information processing has been studied extensively under the heading of ‘Perception’. Chapter 1 discusses such topics as visual acuity, colour vision and our sensitivity to changes in the visual array. The visual system can be usefully characterised as having a limited bandwidth in the temporal and spatial domains and this view is developed to explain the usual recommendations about display parameters such as letter size and refresh rates. Chapter 2 summarises some of the findings from experimental studies of people reading printed and electronically presented text. This chapter also includes a review of work on special problems arising from the use of VDTs.

The third and fourth chapters are concerned with how we store and manipulate information. Human memory is conventionally viewed as a collection of stores of various kinds which have different characteristics. Knowing how these stores function makes it possible to minimise the users’ memory problems. Similarly, knowledge of human reasoning processes makes it possible to understand how we manipulate information. Human memory is discussed in Chapter 3 and reasoning in Chapter 4.

CHAPTER 1

Visual Perception: an Intelligent System with Limited Bandwidth

Peter Thompson

Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses the visual perception of an intelligent system with limited bandwidth. Visual stimuli, be they objects in the real world or patterns on a cathode ray tube, can be described in terms of their size, shape, orientation, color, and movement. In many of these dimensions, the humans’ visual systems act like a filter, responding to some parts of the dimension while remaining oblivious to others. An appreciation of these limitations is important because it guards humans against requiring visual system to perform beyond its physical constraints and because it enables to achieve an economy of representation when constructing visual displays—one do not need to generate those parts of a pattern that will be invisible to the visual system. Many of the constraints on vision are established in the early stages of visual processing and can be traced to aspects of the anatomy and physiology of the peripheral visual system. Other constraints appear at a cognitive level. At this higher level, visual processing appears to be an active process that uses past experience and expectations to aid in its construction of a plausible visual world from seemingly ambiguous sense-data. The rigidity of the physical limitations of the peripheral visual system makes recommendations on the physical dimensions of visual stimuli possible. Whether the use of color, highlighted words, or flashing symbols will help or hinder the user is often impossible to determine outside the particular task being considered. Fortunately, these decisions can be made after reasonably simple experiments have been carried out.

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Vision is our primary sense. Man learns about his environment largely through his eyes, but the human visual system has its limitations and its quirks; and an appreciation of these is an important prerequisite for making the most efficient use of our visual sense to communicate information from the world to our higher cognitive centres.

The message of this chapter is two-fold. Firstly, the visual system acts as a low-pass spatio-temporal filter; this means that there are many things that the eye does not see and that any visual display need not transmit. Secondly, vision is an active process, constructing our visual world from often inadequate information. It is little wonder therefore that the eye is sometimes deceived.

An appreciation of both the physical and the cognitive constraints upon the visual system is important when designing visual displays.

Light

Visible light is that part of the Electro-magnetic spectrum to which our eyes are sensitive, the visible range lying between wavelengths of 400–700 nanometres (nm). At the short-wavelength end of the visible spectrum is ‘blue’ light and at the long-wavelength end is ‘red’ light. The perceived brightness and colour of light depend largely on the physical intensity and wavelength of the light. However, most of the light we see is reflected light, whose perceived brightness and colour depend upon the properties of the surface from which it is reflected, as well as the properties of the illuminant: generally dark surfaces absorb most light, light surfaces absorb little light; ‘red’ surfaces absorb most short wavelengths and ‘blue’ surfaces absorb most long wavelengths, but this is not always the case.

Our Visual Apparatus

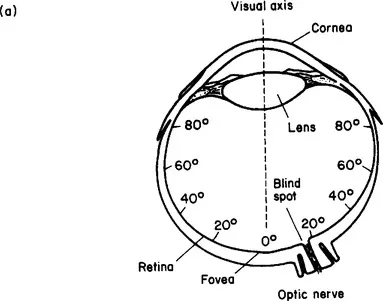

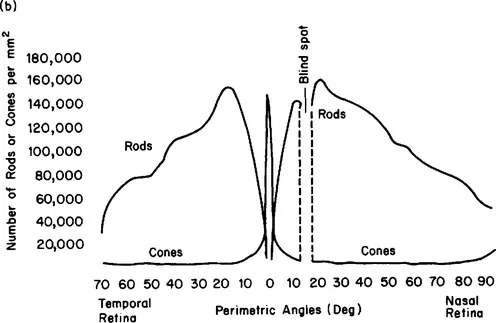

For the purposes of this chapter the human visual system comprises the eyes and those areas of the brain responsible for the early stages of visual processing. The human eye focuses an image of the world upsidedown on the retina, a mosaic of light-sensitive receptors covering the back of the eye (see Figure 1.1a). The photoreceptors of the retina are of two different sorts: rods, which are very sensitive to light but saturate at high levels of illumination, and cones, which are less sensitive and hence can operate at high luminance levels. Humans have three different types of cone, each optimally sensitive to a different wavelength, which allow us to have colour vision. Most of each retina’s 7 million cones are concentrated in the fovea, the small area of the retina (about 0.3 millimetres in diameter) upon which fixated objects are imaged. The rods, 120 million in each retina, predominate in the periphery. Figure 1.1b shows the distribution of rods and cones on the retina. The point from which the optic nerve leaves the retina is devoid of all photoreceptors, this is called the ‘blind-spot’, a surprisingly large area of retina totally insensitive to light. The blind spot is located in the temporal retina, that is, in the half of the retina closer to the temple. The other half of the retina is known as the nasal retina, being closer to the nose. The whole of the retina is covered by a network of blood vessels which lie between the visual receptors and the world. However, these are not usually seen because the visual system rapidly ceases to respond to stimuli which remain unchanging on the retina.

Visual Angle

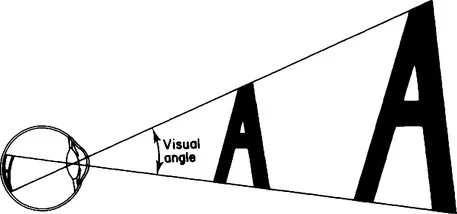

The most widely used measure of image size is the degree of visual angle, see Figure 1.2. An object 1 unit in length placed at a distance of 57 units from the eye produces an image of approximately 1 degree of visual angle upon the retina. Both the sun and the moon subtend angles of about 0.5 degrees (30 minutes). The fovea covers an area of about 1–2 degrees, roughly the size of your thumb-nail at arm’s length, and the blindspot an area of about 5 degrees.

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Computers and People Series

- Copyright

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PART ONE: THE USER AS A PROCESSOR OF INFORMATION

- PART TWO: THE USE OF BEHAYIOURAL DATA

- PART THREE: THE USER INTERFACE

- GLOSSARY

- REFERENCES

- Author Index

- Subject Index