This work was supported by research grants CO7005 from the Department of Defense, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, and NS-26658 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private ones of the author and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the Department of Defense or the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. Experiments reported herein were conducted according to the principles set forth in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,” Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, NIH Pub. No. 80-23.

Publisher Summary

This chapter presents an overview of the upper and lower motor neurons. Anterior horn cells and their peripheral processes (axons), which innervate striated muscle, constitute anatomic and physiologic units referred to as the final common motor pathway or the lower motor neuron. The concept of the lower motor neuron is not limited to spinal cord. Motor cranial nerve nuclei, which innervate muscles in the head and neck, also are classified as lower motor neurons. Anterior horn cells, which are the prototype for all motor neurons, lie in cell columns in the anterior gray horn of the spinal cord. Several distinct cell columns are evident in the anterior horn. A medial cell column extending throughout the length of the spinal cord, which is divisible into cell groups, innervates the long and short axial muscles. The lateral cell column innervates the remaining body musculature. In the thoracic region, the lateral cell column is small and innervates the intercostal and anterolateral trunk musculature. All the descending fibers systems that can influence or modify activities of the lower motor neuron constitute the upper motor neuron.

The Lower Motor Neuron

Anterior horn cells and their peripheral processes (axons), which innervate striated muscle, constitute anatomic and physiologic units referred to as the final common motor pathway, or the lower motor neuron. The concept of the lower motor neuron is not limited to spinal cord. Motor cranial nerve nuclei, which innervate muscles in the head and neck, also are classified as lower motor neurons.

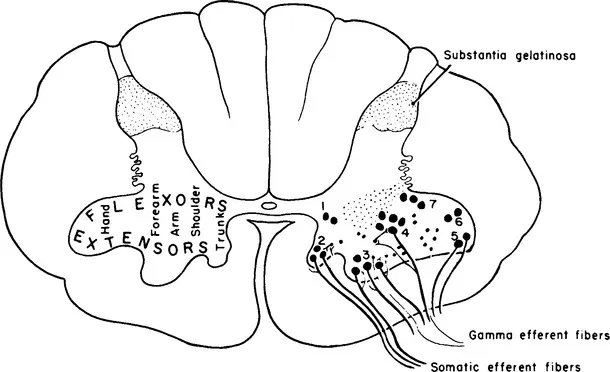

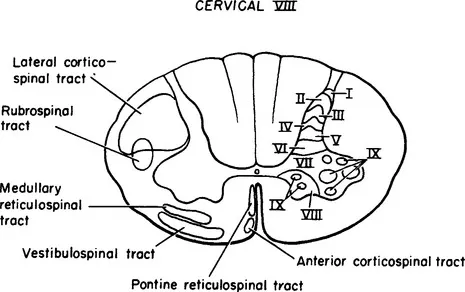

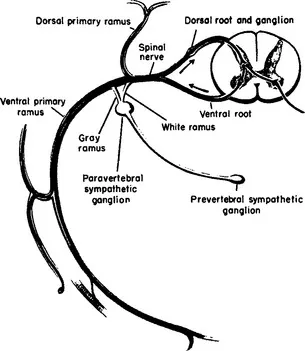

Anterior horn cells, the prototype for all motor neurons, lie in cell columns in the anterior gray horn of the spinal cord. Several distinct cell columns are evident in the anterior horn. A medial cell column extending throughout the length of the spinal cord, divisible into cell groups, innervates the long and short axial muscles. The lateral cell column innervates the remaining body musculature. In the thoracic region the lateral cell column is small and innervates the intercostal and anterolateral trunk musculature. In the cervical and lumbosacral enlargements the lateral cell column enlarges and consists of several large subgroups. Cell groups of the lateral cell column in the cord enlargements innervate the muscles of the extremities. Cells of the lateral column, located anteriorly and peripherally, innervate extensor and abductor muscle groups; cells located dorsal and central to these innervate flexor and adductor muscle groups (Figure 1-1). The spinal gray matter has cytoarchitectural lamination that divides it into separate zones.1,2 Anterior horn cells lie with Rexed’s lamina IX, characterized by large motor neurons, 30 to 100 μ in diameter (Figure 1-2). These large multipolar neurons have coarse Nissl granules, large central nuclei, and multiple dendrites that extend beyond the limits of lamina IX. Axons of these cells emerge via the ventral root and become mixed with dorsal root fibers distal to the dorsal root ganglion. Spinal nerves containing both motor and sensory fibers are referred to as mixed spinal nerves. Fibers of the mixed spinal nerve divide into dorsal and ventral primary rami (Figure 1-3). In the spinal enlargements the primary rami participate in plexus formation, resulting in the formation of the brachial and lumbosacral plexuses. Nerves given off from these plexuses provide innervation for the muscles of the upper and lower extremities.

Figure 1-1 Diagram of the motor nuclei of the anterior gray horn in a lower cervical spinal segment. On the left, the approximate locations of neurons innervating different muscle groups are shown. On the right, groups of motor neurons are indicated by numbers. Both alpha and gamma fibers are shown emerging from the anterior horn. (From Carpenter MB. Core Text of Neuroanatomy, ed 3. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1985.)

Figure 1-2 Drawing of a transverse section of the spinal cord at C-8 with the laminae of Rexed on the right and the position of the principal descending tracts indicated on the left.

Figure 1-3 Schematic diagram of a thoracic spinal nerve showing peripheral branches and central connections. (From Noback CR, Demarest RJ. The Human Nervous System, ed 3. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981.)

Not all cells in the anterior gray horn innervate striated muscle. Some, usually smaller than motor neurons, have processes confined to the spinal cord. These cells, referred to as internuncial neurons, have axons that project to other segments, to the opposite side of the spinal cord, or to motor neurons. Cells whose axons emerge from the spinal cord are known as root cells; these cells subserve effector functions. Root cells of the anterior horn are of two types: (1) alpha (α) motor neurons give rise to large fibers that innervate striatal (extrafusal) muscle and (2) gamma (γ) motor neurons innervate muscle spindles (intrafusal; Figures 1-2 and 1-4). The spectrum of myelinated fibers in the ventral roots indicates two groups of fibers. Approximately 70% of the fibers are between 8 and 13 μm in diameter and are classified as alpha fibers; the remaining 30% of the fibers, 3 to 8 μm in diameter, are designated gamma fibers. In addition, the ventral roots in thoracic and upper lumbar spinal segments contain unmyelinated or poorly myelinated preganglionic sympathetic fibers. Sacral ventral roots (S-2, S-3, and S-4) contain similar poorly myelinated preganglionic parasympathetic fibers. These preganglionic fibers project to various autonomic ganglia.

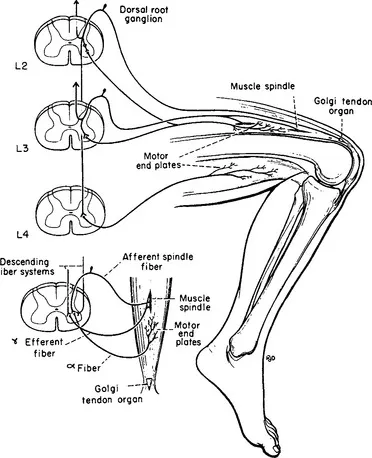

Figure 1-4 Schematic diagram of the sensory and motor elements involved in the patellar tendon reflex. Muscle spindle afferents are shown entering only the L-3 spinal segment; Golgi tendon organ afferents are shown entering only the L-2 segment. In this monosynaptic reflex afferent fibers enter L-2, L-3, and L-4 spinal segments and efferent fibers from the anterior horn cells at these same levels project to the extrafusal muscle fibers of the quadriceps femoris. Efferent fibers from L-4 projecting to the hamstrings represent part of the pathway involved in reciprocal inhibition. The small diagram on the left illustrates the gamma loop. Contractions of the polar parts of the muscle spindle initiate an afferent volley conducted centrally to alpha motor neurons. Discharge of the alpha motor neuron is conveyed to the motor end-plate of the same muscle. The gamma efferent fiber controls the sensitivity of the muscle spindle. (From Carpenter MB. Core Text of Neuroanatomy, ed 3. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1985.)

Alpha motor neurons are cholinergic and terminate upon skeletal muscle fibers in small, flattened expansions known as motor end-plates, which constitute the so-called myoneural junction. Electrical stimulation of a motor nerve causes quanta of acetylcholine (ACh) to be liberated at the myoneural junction, which produces contractions of muscle fibers. Following the contractions, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) hydrolyzes the ACh. Stimulation of a muscle nerve with graded shocks results in twitches of the muscle related directly to the strength of the stimulus, until the alpha spike reaches its full potential. Increasing the size of the stimulus does not produce a stronger contraction, even though gamma fibers may be discharged. Thus, impulses conducted by alpha motor fibers are related to the contractile elements of striated muscle and gamma motor neurons do not contribute directly to muscle contraction. Gamma fibers are distributed to the polar (contractile) portions of the muscle spindles. Contraction of the polar portions of the muscle spindle may be sufficient to cause the discharge of muscle spindle afferent fibers (group IA), but these contractions do not directly alter muscle tension or length. Impulses conducted by group IA enter the spinal cord via the dorsal root and distribute collaterals directly on alpha motor neurons. This two neuron linkage (one sensory neuron in the dorsal root ganglion and one motor neuron in the ventral horn) establishes part of the so-called gamma loop. The loop is closed by gamma efferent fibers, which arise from cells in the anterior horn and pass directly to polar parts of the muscle spindle (see Figure 1-4). Thus, impulses conveyed by gamma motor neurons can indirectly excite alpha motor neurons by causing the muscle spindle to fire. Part of this mechanism forms the basis for the myotatic (or stretch) reflex. Only part of the afferents from the muscle spindle pass to the anterior horn; a large part of the afferent volley ascends via relays in the spinal cord to the cerebellum.

The myotatic or deep tendon reflex is a monosynaptic reflex dependent on two neurons: one neuron in the dorsal root ganglion that receives afferent impulses from the muscle spindle and the alpha motor neuron that innervates the striated muscle containing the mus...