- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pascal for Students (including Turbo Pascal)

About this book

The third edition of this best-selling text has been revised to present a more problem oriented approach to learning Pascal, without substantially changing the original popular style of previous editions. With additional material on Turbo Pascal extensions to the standard Pascal, including binary files and graphics, it continues to provide an introduction which is as suitable for the programming novice as for those familiar with other computer languages.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section 1

Pre-defined simple types and control structures

1

First steps

Introduction

The very simplest kinds of computer program are introduced in this chapter. Even so there is much to learn—the basic structure of Pascal programs, how to feed in data and layout results, but most of all how to get the computer to do what you want it to and find out what’s going wrong when it doesn’t.

1.1 Some simple programs

Computers, like the Delphic Oracle, are used to answer questions, but, as with the Oracle, you have to be careful how you phrase your request or you may get a misleading answer. In fact the computer may give you no answer at all if it doesn’t like the question.

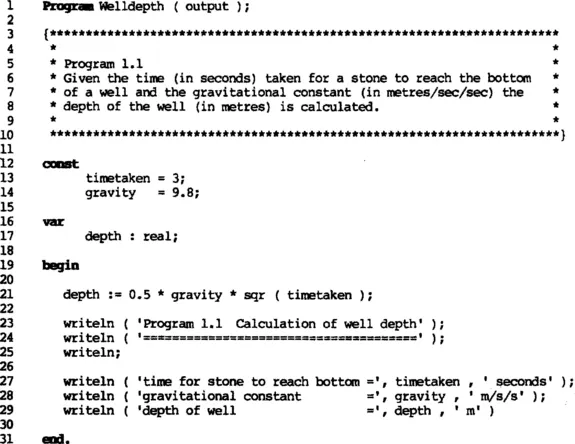

The first question we shall ask the computer is: ‘given that a stone takes 3 seconds to reach the bottom of a well how deep is the well?’ It would be nice if we could phrase the question exactly in this way and expect the computer to get the right answer. It will be a few years before that becomes possible. In the meantime the best way to get the computer to provide an answer is to write a computer program to do the job. Program 1.1 does just this. Before we examine the program in detail have a preliminary look at it to see if you can work out what’s happening.

Program 1.1

Ignoring much of the punctuation for now let’s look at the program line by line. (Note that the line numbers that appear on the left-hand side are for reference only and are not part of the program.)

On the first line the program is given a title. The user chooses an appropriate name but, as with all Pascal names, there must be no break in the middle—Well depth would not work. The name output in parentheses, signifies that the answer that the computer gives should be transmitted to the device called output. This might be a printer*, vdu* or teletype*. Lines 3 to 10 contain a description of the purpose of the program. This description enclosed between braces ‘{’ and ‘}’ is known as a comment. In all programs, whatever the language, it is important to have a piece of text at or near the beginning describing the purpose of the program and, possibly, giving other information such as the name of the writer and the date of completion. In Pascal, any information enclosed between ‘{’ and ‘}’ is disregarded by the compiler* (even if it extends over several lines) and so explanatory text may be inserted at appropriate points#. In this example the rectangle of asterisks has no significance for the computer but helps to highlight the enclosed introductory description for the reader.

A blank line follows, and then, on lines 13 and 14, the constants to be used in the program are given values. In order to work out the depth of the well the computer needs to know how long a stone takes to reach the bottom and also how fast it is moving. The time taken was 3 seconds and a name timetaken has been invented to represent this. Note, again, that it would not be acceptable to have a name in two parts (time taken). There must be no spaces in the middle. The second constant 9.8 is given the name gravity. The stone actually falls because of the gravitational pull of the earth and if we are to determine the depth of the well this will be needed too.

After the next blank line, the word var (short for ‘variable’) indicates that the name following it denotes a variable in the program. The word that follows is depth and represents the depth of the well. At this point you may be wondering why depth is called a variable giving the impression that it is something that alters. Surely the depth remains unchanged in the same way that the time taken and the gravitational constant do? The distinction occurs because we know the values of the constants before we start but the value of the depth is to be calculated in the program itself. In Pascal any names used to denote values that are computed during the running of a program are designated as variables.

The fact that the depth will be a number which will probably contain a fractional part is indicated by placing the word real after the variable name.

None of the code up to line 17 actually commands the computer to carry out the task we are interested in. However, the directions on lines 12 to 17 are important to the organisation of information within the computer and to the execution of the code contained between the words begin and end in the ‘statement part’.

The code on line 21 computes the depth from ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface to the first edition

- Preface to the second edition

- Preface to the third edition

- Introduction

- Section 1: Pre-defined simple types and control structures

- Section 2: Structured and enumerated data types

- Section 3: Turbo Pascal

- Section 4: Mathematical applications of Turbo Pascal

- Appendix A: Syntax diagrams for Pascal

- Appendix B: Reserved words and required identifiers

- Appendix C: Required functions and procedures

- Appendix D: Turbo Pascal functions and procedures

- Appendix E: Common codes

- Appendix F: Portability

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Pascal for Students (including Turbo Pascal) by Ray Kemp,Brian H. Hahn,Brian Hahn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Programming Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.