Entity Resolution

Entity resolution (ER) is the process of determining whether two references to real-world objects are referring to the same object or to different objects. The term entity describes the real-world object, a person, place, or thing, and the term resolution is used because ER is fundamentally a decision process to answer (resolve) the question, Are the references to the same or to different entities? Although the ER process is defined between pairs of references, it can be systematically and successively applied to a larger set of references so as to aggregate all the references to same object into subsets or clusters. Viewed in this larger context, ER is also defined as “the process of identifying and merging records judged to represent the same real-world entity” (Benjelloun, Garcia-Molina, Menestrina, et al., 2009).

Entities are described in terms of their characteristics, called attributes. The values of these attributes provide information about a specific entity. Identity attributes are those that when taken together distinguish one entity from another. Identity attributes for people are things such as name, address, date of birth, and fingerprint—the kinds of things often asked for to identify the person requesting a driver's license or hospital admission. For a product identity, attributes might be model number, size, manufacturer, or universal product code (UPC).

A reference is a collection of attributes values for a specific entity. When two references are to the same entity, they are sometimes said to co-refer (Chen, Kalashnikov, Mehtra, 2009) or to be matching references (Benjelloun, et al., 2009). However, for reasons that will be clear later, the term equivalent references will be used throughout this text to describe references to the same entity.

An important assumption throughout the following discuss of ER is the unique reference assumption. The unique reference assumption simply states that a reference is always created to refer to one, and only one, entity. The reason for this assumption is that in real-world situations a reference may appear to be ambiguous—that is, it could refer to more than one entity or possibly no entity. For example, a salesperson could write a product description on a sales order, but because the description is incomplete, the person processing the order might not be clear about which product is to be ordered. Despite this problem, it was the intent of the salesperson to reference a specific product. The degree of completeness, accuracy, timeliness, believability, consistency, accessibility, and other aspects of reference data can affect the operation of ER processes and produce better or worse outcomes. This is one of the reasons that ER is so closely related to the field of information quality (IQ).

Background

The concepts of entity and attribute are foundational to the entity-relation model (ERM) that is at the very core of modern data modeling and database schema design. The entity-relation diagram (ERD) is the graphical representation of an ERM and has long been considered a necessary artifact for any database development project. The relational model, first described by E. F. Codd (1970), was later refined into what we now know as the ERM by Peter Chen (1976). In the ERM, information systems are conceptualized as a collection of entities, each having a set of descriptive attributes and also having well-defined relationships with other entities.

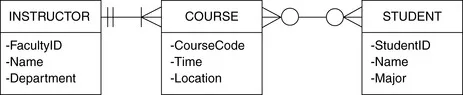

Figure 1.1 shows a simple ERD illustrating a data model with three entity types: Instructor, Course, and Student. The line connecting the Instructor and Course entity types indicates that there is a relation between them. Similarly, the diagram shows that Course and Student entity types are related. Furthermore, in the ERD style used here, the adornments on the relation line give more detail about these relationships. For example, the triangular configuration of short lines, sometimes called a crow's foot, at the junction of the relation line with an entity indicates a many-to-one relationship. In this example it indicates that one Instructor entity may be related to (be the instructor for) more than one Course entity. The additional adornment of a single bar with the crow's foot further constrains the relation by indicating that each Instructor entity must be related to (assigned to) at least one Course entity. The double bar at the junction of this same relation and the Instructor entity is used to indicate an exactly-one relationship. Here it represents the constraint that each Course entity must be related to (has assigned to it) one, and only one, Instructor entity. The crow's foot symbol with a circle that appears at both ends of the relation between the Course and Student entities indicates a zero-to-many relation. This means that any given Student entity may be related to (enrolled in) several Course entities, or in none. Conversely, any given Course entity may be related to (have in it) several Student entities, or none.

Each entity type also has a set of attributes that describes the entity. For example, the Instructor entity type has the three attributes FacultyID, Name, and Department. Assigning values to these attributes defines a particular instructor, called an instance of the Instructor entity. By the previous definition, an instance of an entity is also an entity reference. A fundamental rule of ERM is that every instance of an entity should have a unique identifier. Codd (1970) called this the Entity Identity Rule. A primary key is an identity attribute or group of identity attributes selected by the data modeler because the combination of values taken on by these attributes will be unique for each entity instance. However, at the design stage, it is not always clear that a particular combination of descriptive attributes will have this property, or it if does, that the combination will continue to be unique as more instances of the entity are acquired. For this reason data modelers often play it safe by adding another attribute to an entity type that does not describe any intrinsic characteristic of the entity but is simply there to guarantee that each instance of the entity has a primary key. For example, in Figure 1.1, with only name and department as the identity attributes for the Instructor entity, it is conceivable that a department could have two instructors with the same name. If this were to happen, the combination of name and department would no longer meet the requirements to form a primary key. By adding a FacultyID attribute as a third attribute and by controlling the values assigned to FacultyID, it is possible to guarantee that each instance of the Instructor entity has a unique primary key value. Called surrogate keys, the values for these artificial keys have no intrinsic meaning, such as a FacultyID value of “T1234” or an Employee_Number of “387.”

In theory, ER should never be a problem in a well-designed database because two entity instances should be equivalent if, and only if, they have the same primary key. When this is true, it allows information about the same entity in different tables of the database to be brought together by simply matching instances with the same primary key value through what is called a table join operation.

The problem is that these artificial primary keys must be assigned when the instance is entered into the database and maintained throughout the life cycle of the entity, and there is no guarantee that this will always be done correctly. An even greater problem is that the same entity may be represented in different databases or even different tables within the same database, using a different primary key. In other situations the references may lack key values because they came from a nondatabase source or were extracted from a database without including the key. ER in a database context is sometimes referred to as the problem of heterogeneous database join (Thuraisingham, 2003; Sidló, 2009).

ER systems that provide heterogeneous database join functionality are often employed by law enforcement and intelligence agencies, where each agency maintains a separate database of entities of interest, with each using a different scheme for primary keys. In this setting, the ER system acts as a “hub” that connects to each of the databases. When an entity reference from an investigation is entered, the system reformats the reference information as a query appropriate to each database and returns the matching results to the user. The Identity Resolution Engine® by Infoglide Software®, discussed in Chapter 5, is an example of a commercial system that provides this type of functionality. Chapter 7 discusses the growing trend to use ER hub architectures as a solution to the problem of bringing together information about a common set of entities held in independently maintained systems...